Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Love stinks: Patrice Chéreau’s 1983 film about a young Frenchman’s sexual awakening in a train station, initially inspired by

Jean Genet’s autobiography.

Jean-Hugues Anglade as Henri and Vittorio Mezzogiorno as Jean Lerman in The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

The Wounded Man, directed by Patrice Chéreau, available on Blu-ray and DVD from Altered Innocence May 23, 2023

• • •

The late French maestro Patrice Chéreau—who directed not only films but also operas and plays, led a highly regarded drama school, and acted occasionally—was drawn to stories of outsize, ungovernable emotions. In Queen Margot (1994), his most commercially successful movie, crazed kings sweat blood and royals rut in the street while all of Paris becomes a graveyard, the avenues clogged with butchered bodies in the aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Similarly clamorous and densely populated, Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train (1998) also reveals Chéreau’s talent for adeptly orchestrating psychic chaos, as a series of tempestuous couples and exes—of multiple sexualities—bicker, reconcile, and fall out once more.

Jean-Hugues Anglade as Henri and Vittorio Mezzogiorno as Jean Lerman in The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

Yet he also excelled at more modestly scaled portraits of people coming undone by their needs, particularly when they can’t articulate them. That’s especially the case with 1983’s The Wounded Man (L’homme blessé), the new 4K restoration of which is now available on home video from Altered Innocence. Wanting to make a film about “the subproletariat of homosexuality,” Chéreau drew inspiration from Jean Genet’s highly autobiographical The Thief’s Journal. Chéreau and his cowriter, the novelist and photographer Hervé Guibert—both openly gay—worked on the script for six years. (Although it was Chéreau’s third movie—following The Flesh of the Orchid, a baroque thriller from 1975 starring Charlotte Rampling at the peak of her decadent glamour, and 1978’s Judith Therpauve, with Simone Signoret as a French Resistance vet determined to save a gauchiste newspaper—he would waggishly hail The Wounded Man, a much more personal project, as his first.) After finding that an adaptation of Genet’s book wasn’t quite working, he and Guibert, as Chéreau explained in 1985, “kept only the basic idea: an impossible love story between a young boy and an older guy who disappears all the time.”

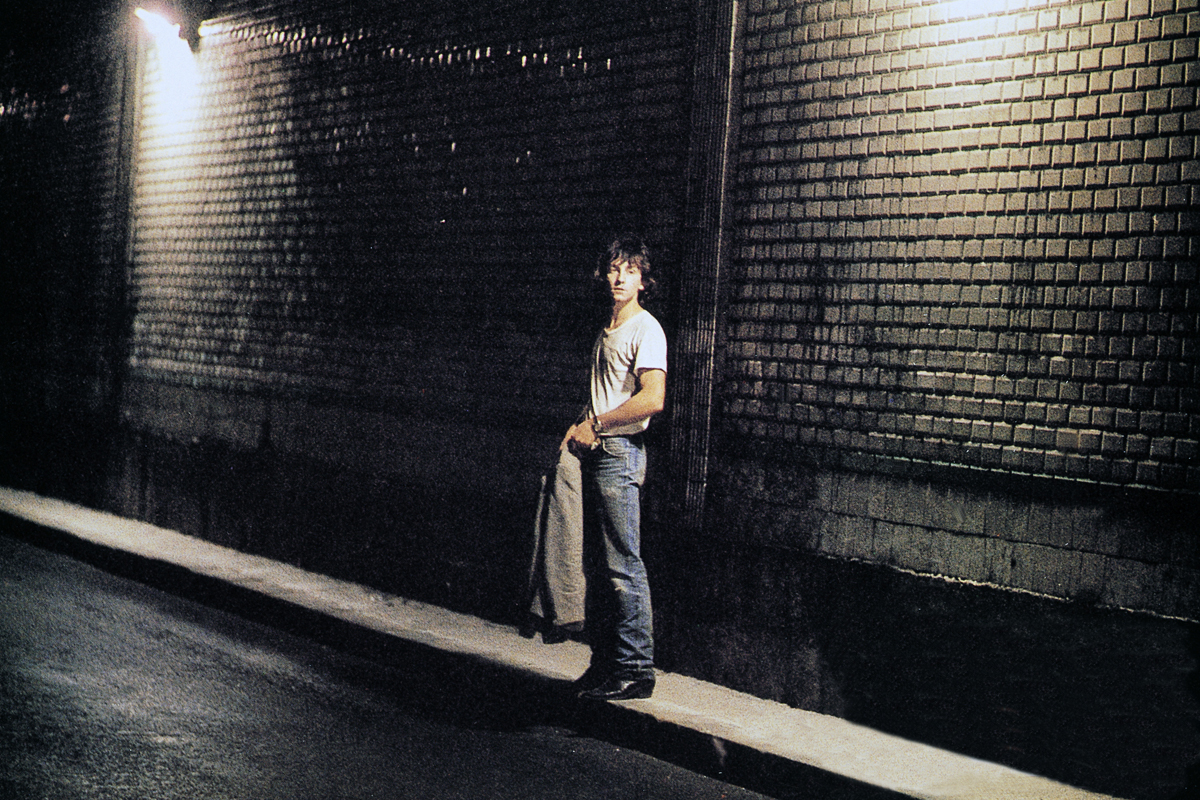

Jean-Hugues Anglade as Henri in The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

That “young boy” is twenty-year-old Henri (Jean-Hugues Anglade), who still lives at home—a flat so cramped that his parents sleep on a fold-out sofa in the living room—in an unnamed town. While a fleetingly glimpsed pile of typewritten pages on his twin bed suggests either an academic pursuit or his own prose efforts, Henri appears to have nothing better to do with his time than accompany the family to the train station (an uncredited Gare du Nord), where his younger sister is leaving for a program in Frankfurt.

Roland Bertin as Bosmans in The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

But in one of the waiting rooms of the rail station, something feral awakens in this guileless youth, sporting a shawl-collar cable cardigan that further underscores his innocence. He locks eyes with Bosmans (Roland Bertin), a nattily attired, portly, middle-aged gent, who’s long treated the transportation hub as a cruising ground. Henri seems at once attracted to and repelled by this man, aimlessly racing through the station—but is he hoping to escape or meet up with the fop? Descending into the bowels of the depot, Henri encounters a butch beauty named Jean (Vittorio Mezzogiorno, an Italian actor dubbed by Gérard Depardieu), who enlists the stripling to help him rough up an elderly john. The initiation rite complete, Jean rewards the tyro with a kiss.

Jean-Hugues Anglade as Henri and Vittorio Mezzogiorno as Jean Lerman in The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

So begins a frenzied, compulsive circuit for Henri, his manic actions punctuated by avant-jazz godhead Albert Ayler’s explosive saxophone on the soundtrack. He cannot stay away from the station for more than a few hours, where he pursues or is pursued by Bosmans, used by Henri in the hopes of being reunited with the elusive Jean, with whom he is besotted. Reedy and twitchy, Anglade appears here in his first lead role; he would become a star later in the ’80s thanks to his work in the films of Luc Besson and Jean-Jacques Beineix, pioneers of the cinéma du look, a movement distinguished by its gossamer artifice and striking color palette. Although a few vibrant hues speckle Chéreau’s film—the pink neons of the run-down carnival where Henri doggedly trails Jean; the red-and-white glow of a Coke machine (its exhortation, Servez-vous, “serve yourself,” an apt tagline) next to a scrum of young hustlers huddled by a depot staircase—grim slate grays and other muted, muddied tones dominate.

Vittorio Mezzogiorno as Jean Lerman and Jean-Hugues Anglade as Henri in The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

Another of the basic senses prevails: The Wounded Man might be thought of as an exemplar of cinéma du smell. Effluvia seem to drift off the screen directly into our nostrils, whether Henri’s b.o. (his mother remarks that he hasn’t taken a shower in a while); the stench of the railway lavatory bustling with tearoom trade; the pungent scent of Jean’s soiled uniform of blazer, T-shirt, and faded jeans—duds that, left behind in the apartment the brute stud shares with an infinitely forbearing girlfriend (Lisa Kreuzer), the much smaller Henri will don as yet another display of his deranging infatuation.

Still from The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

Shot in 1982—the same year the CDC first used the term “AIDS” to name the burgeoning health crisis that was only just beginning to be understood—The Wounded Man stands as one of the last films alighting on gay life that, although not technically produced during the pre-AIDS era, would not feel an obligation to address the disease. (Diagnosed with the illness in 1988, Guibert would candidly document the ravages of AIDS on his body in books and in a video, which aired on French television after his death in 1991.) Like Cruising and the German Taxi zum Klo (Taxi to the Toilet), both of which premiered in 1980, Chéreau’s movie—the potency of its unsanitized eros diminished slightly by the too-predictable final-act liebestod—blithely renounced the “positive images” then being demanded by gay activists. (That demand hasn’t entirely faded away, of course, and is only one aspect of the larger, reductive debates surrounding the “politics of representation.”)

Jean-Hugues Anglade as Henri in The Wounded Man. Courtesy Altered Innocence.

Although gay characters appear in later Chéreau films—as in the abovementioned Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train and Son Frère (2003), which traces the rapprochement between two estranged siblings, one hetero, the other homo—he “never wanted to specialize in gay stories,” as he told the Guardian in 2011, two years before his death, at age sixty-eight. “Everywhere love stories are exactly the same. The game of desire, and how you live with desire, are the same.” The Wounded Man demonstrates the sordid transcendence, the ennobling ludicrousness of that game.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.