Kirsty Bell

Kirsty Bell

In a career retrospective of over three hundred works by the German conceptual artist, a refusal to be one thing.

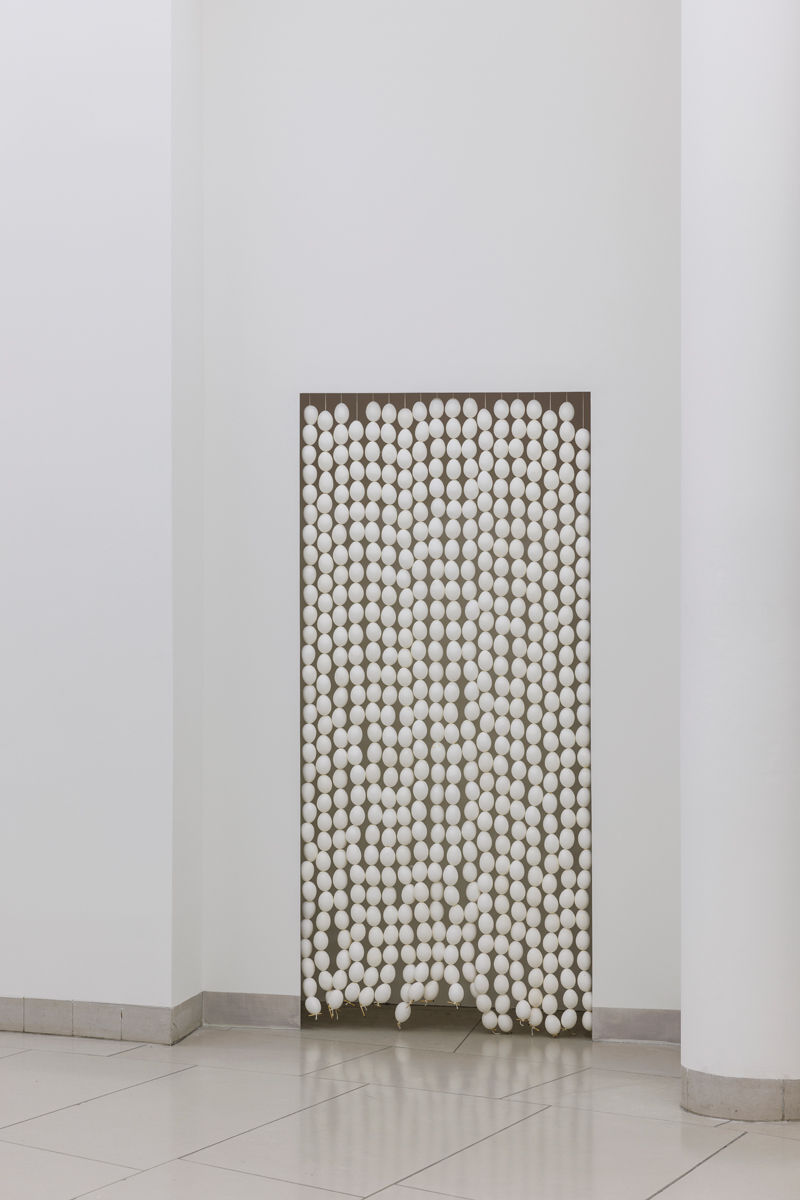

Rosemarie Trockel, installation view. Courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Frank Sperling. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

Rosemarie Trockel, curated by Susanne Pfeffer, Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK), Domstraße 10, Frankfurt am Main, Germany,

through June 18, 2023

• • •

Occupying all three floors of Frankfurt’s MMK, Rosemarie Trockel offers an exceptional opportunity for immersion into a vast and varied oeuvre of unabashed complexity. A timely and powerful antidote to stripped-down, polarizing arguments, it embraces contradictions and overlapping meanings, and can occasionally lead to blank failures of comprehension on the viewer’s part. The show, which opened just after Trockel’s seventieth birthday, is the latest in a steady stream of exhibitions that began in the 1980s in her hometown of Cologne. But this is by far the most comprehensive. It touches all the bases of her prolific output: black-and-white videos featuring animals or people, knobbly ceramic sculptures, knitted paintings, drawings, digital prints, casts of limbs or domestic furnishings, vitrine assemblages, and even, this time, oil paintings, albeit commissioned by Trockel and made by others.

Rosemarie Trockel, installation view. Courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Frank Sperling. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst. Pictured, back left wall: Thanks Mr Djerassi, 2003/2022.

The over three hundred works brought together do not lay out evidence of an aesthetic trajectory—stepping stones in a successful artist’s career—but rather proffer skewed proposals or open-ended investigations, often tinged with violence or hints of oppression. At no point does Trockel’s work settle into clear resolution. Each piece asks questions and is more likely to spawn further questions than offer up answers. Your best option is to trust in your gut and your nerves as much as your eyes. “Finally to sense, and not just to know,” is how Trockel puts it.

Rosemarie Trockel, Untitled, 1998. Courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Frank Sperling. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

An ultramarine lattice is silkscreened onto the walls of the museum’s lofty atrium. Its looping pattern refers to Trockel’s celebrated Strickbilder, or knitted pictures, for which she received early acclaim. Though appropriating a female-designated practice, these knitted panels—machine-made and adorned with logos and trademarks—slip from feminine domesticity into the realms of mass consumerism and production. Simplistic gender dichotomies fall short as feminist politics intersect with other overarching structures. Unlike woven canvas, a knitted panel stretched over a frame does not provide a stable foundation. It is elastic, textured, and—constructed from a single thread—has the propensity to unravel. Prisoner of Yourself (1998), the title of the wall pattern, suggests Trockel is trapped by her own appealing artistic signature. But are we the prisoners here, reluctant to abandon fixed ways of seeing or thinking for the open plains of doubt? This deceptively simple work exemplifies Trockel’s powers of transformation: of thought-process into material, but also one material into another. Her signature technique becomes a drawing of knitting, painstakingly screen-printed onto the walls. The work enmeshes us in the artist’s imagination—this Trockel-ish view of sideways inflection and constantly shifting ground.

Rosemarie Trockel, installation view. Courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Frank Sperling. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

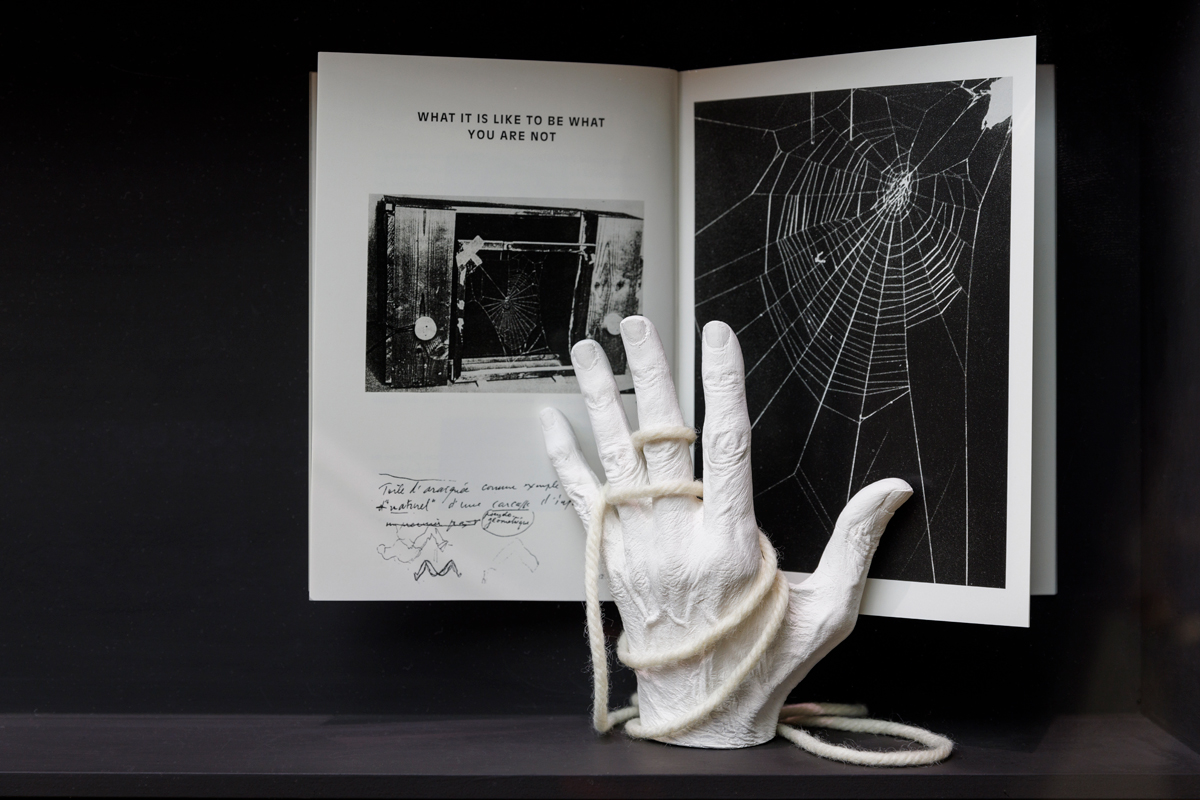

In an adjacent room, three walls are given over to a group of small handmade books, fifty-eight in total, dating from 1982 to 2003. Displayed salon-style across the walls and titled Book Drafts, each is a cover without content, a draft not followed up on. Not simply works on paper, they masquerade as entry points to something of greater complexity. Similar false thresholds occur throughout Trockel’s art, in windows you cannot see through, mirrors that don’t reflect, masks that conceal true identity. In each case the surface is a talisman signaling some deeper unseen quality, like a flag marking imagination itself.

Rosemarie Trockel, installation view. Courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Frank Sperling. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

The book covers juxtapose image and text, introducing Trockel’s riddling, irony-laced approach to language. The words Ich bin Dan Graham grace a photograph of Trockel in front of a fascist architectural structure. Most Needed Beauty is the handwritten title on a portrait of the elderly Agnes Martin, no conventional beauty by any standards. In the discrepancies between picture and language, a space is prized open that continues in oblique relations of titles to works throughout the show. Three diverse pieces share the title Less Sauvage than Others: a platinum glazed wall panel from 2006, a ceramic leg on a tabletop beside a glass of whiskey (2006/2011), and a collection of bronze replicas of toy guns (2012). What happens in the distance between language and object, or one work and another? Is it space for thought? Or subjectivity? Or even, simply, comprehension?

Rosemarie Trockel, installation view. Courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Frank Sperling. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst. Pictured, left foreground: Less Sauvage than Others, 2006/2011.

These two galleries make for a powerful start, staking out the leitmotifs and intentions of an exhibition that is exhaustive and demanding, given that so much meaning emerges through juxtaposition or dissonance and refuses to coalesce. Broadly chronological as it moves up floor by floor, the show is immaculately installed in the MMK’s eccentrically angular postmodern rooms, many accented with strongly colored walls or carpeting. It is the latest in Susanne Pfeffer’s decisive and timely program of solo exhibitions since she became director in 2018 and features key works from the museum’s collection, including significant early pieces. Everything here is given plenty of space to reverberate and manifest its contradictions, as the show drops a pin in this moment of time to ask what this art can tell us now?

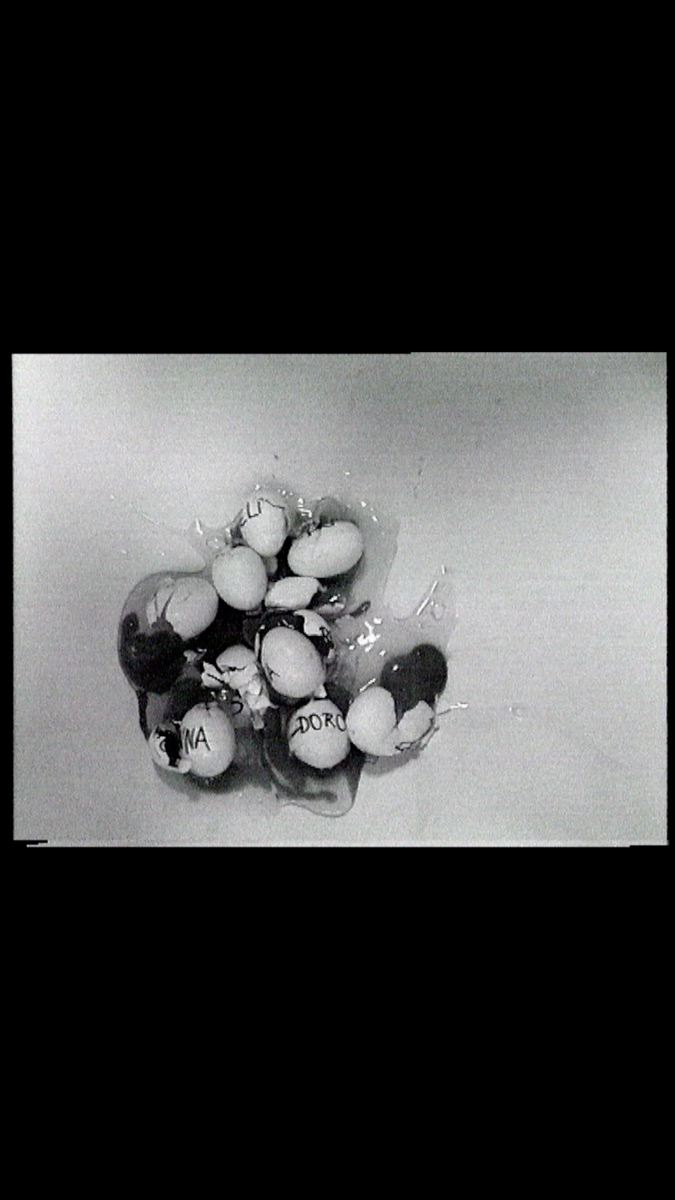

Rosemarie Trockel, Ei-Dorado, 1992 (still). Video, color, sound, 1 minute 57 seconds. Courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

Certain key themes recur, one of which is the experience of gender. Trockel is famously reticent, and her practice refuses biographical particularity to dwell instead on how it is to be a young girl, or a woman of twenty, or fifty, or seventy, especially one whose creativity is not limited to her reproductive organs. Eggs appear in many forms, often comic: strung on threads to form a bead curtain or inscribed with names and filmed jiggling on-screen to Janis Joplin’s Cry Baby, until one by one they break (Ei-Dorado, 1992). Elsewhere, large slabs of blood-red glazed ceramic may refer to the meat industry but also suggest menstruation. One of several self-portraits pictures Trockel aged fifteen, wearing shorts and squinting at the camera, its title a dedication to the best-known scientist behind the pill (Thanks Mr Djerassi, 2003/2022). Despite medical milestones in sexual health, the road to emancipation is not smooth, as current struggles over policing women’s bodies still testify. Stell dir vor, instructs the text on the back of the parka worn by a blond-haired mannequin, one of Trockel’s many alter egos: imagine.

Rosemarie Trockel, Stell dir vor, 2002. Courtesy Sprüth Magers. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

Trockel grew up in postwar West Germany, a severed nation whose economic success was a paradox built on failure, loss, and shame, and where gender relations were characterized by a reactionary conservatism. In this former totalitarian state paralyzed by its recent past, the many things that went unuttered carried just as much weight, if not more, than what was said out loud; there was an underlying atmosphere that reeked of mistrust. Though the politics of this time are rarely addressed directly in Trockel’s works, it makes sense that for her meaning exists in interstices.

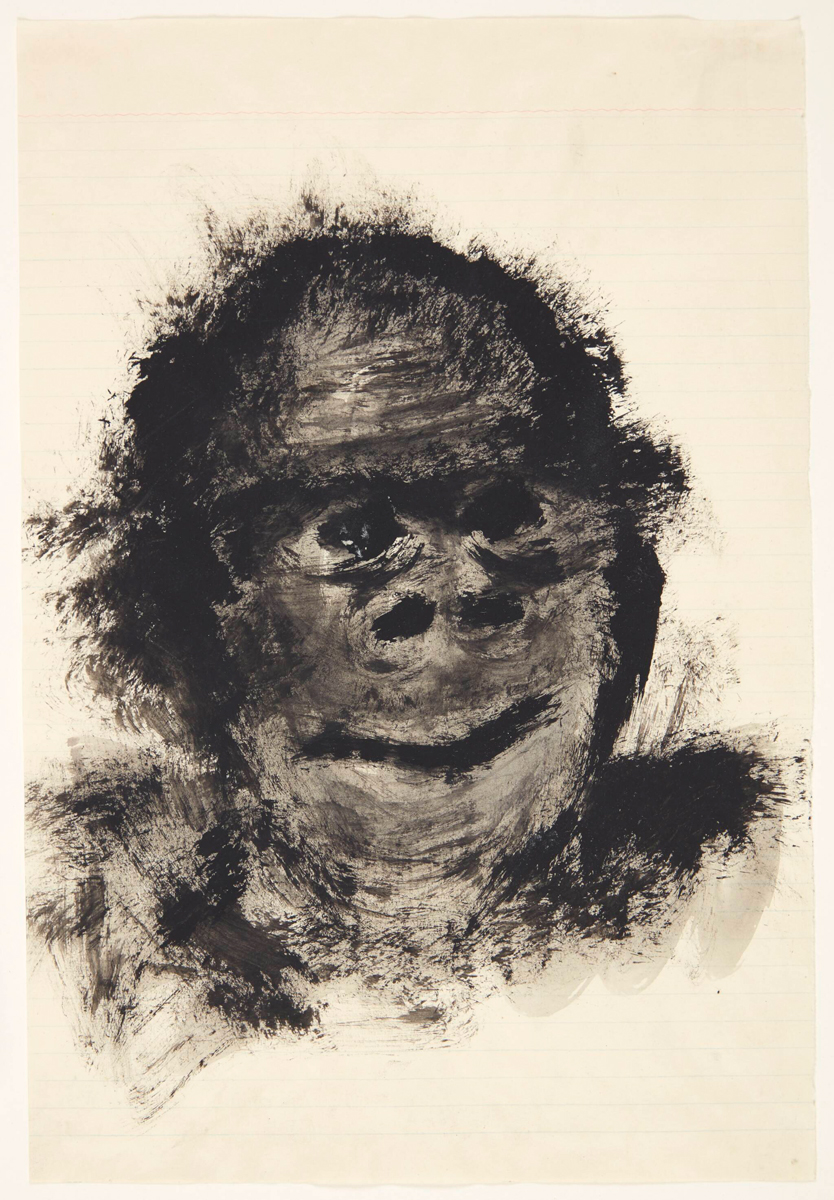

Rosemarie Trockel, Hoffnung, 1984. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

Beyond the decidedly feminist perspective of Trockel’s sociologically oriented practice, a lateral connection extends to the natural world. Animals are persistent subjects in pieces that recalibrate interspecies relations through eye-level observation rather than preordained hierarchies—an approach that is particularly current, given ongoing talk of “companion species” and tree communities. An early film, Napoli (1994), captures starling murmurations set to the strains of Jimmy Hendrix. Both bird patterns and guitar licks can seem like sorcery to our limited human comprehension. In one darkened room, an herbarium of wall-mounted vitrines containing dried plant specimens includes casts of primatologist Jane Goodall’s hand; another room features a series of ink-and-gouache portraits of monkeys, remarkable for their tenderness (Hoffnung, 1984).

Rosemarie Trockel, Musicbox, 2013 (detail). Photo: Frank Sperling. © Rosemarie Trockel and VG Bild-Kunst.

This retrospective, not simply a series of greatest hits, won’t let itself be reduced. Instead, it unfolds to vast proportions. Suspicious of polemic or fixed ideologies, categories or hierarchies, the work points to understandings rooted in material and form, rather than language. Here, both art-making and exhibition-making are dynamic processes of reappraisal, and imagination is a necessary tool for transcending preconceptions or hastily drawn conclusions. When meanings reveal themselves slowly, or later, or not at all, a strangely vibrating residue of curiosity remains.

Kirsty Bell is a writer and art critic living in Berlin. Her book The Undercurrents. A Story of Berlin was published in 2022 by Fitzcarraldo Editions (UK) and Other Press (US).