Eric Banks

Eric Banks

In Antonio Muñoz Molina’s new book, Lisbon is a city of assassins and writers.

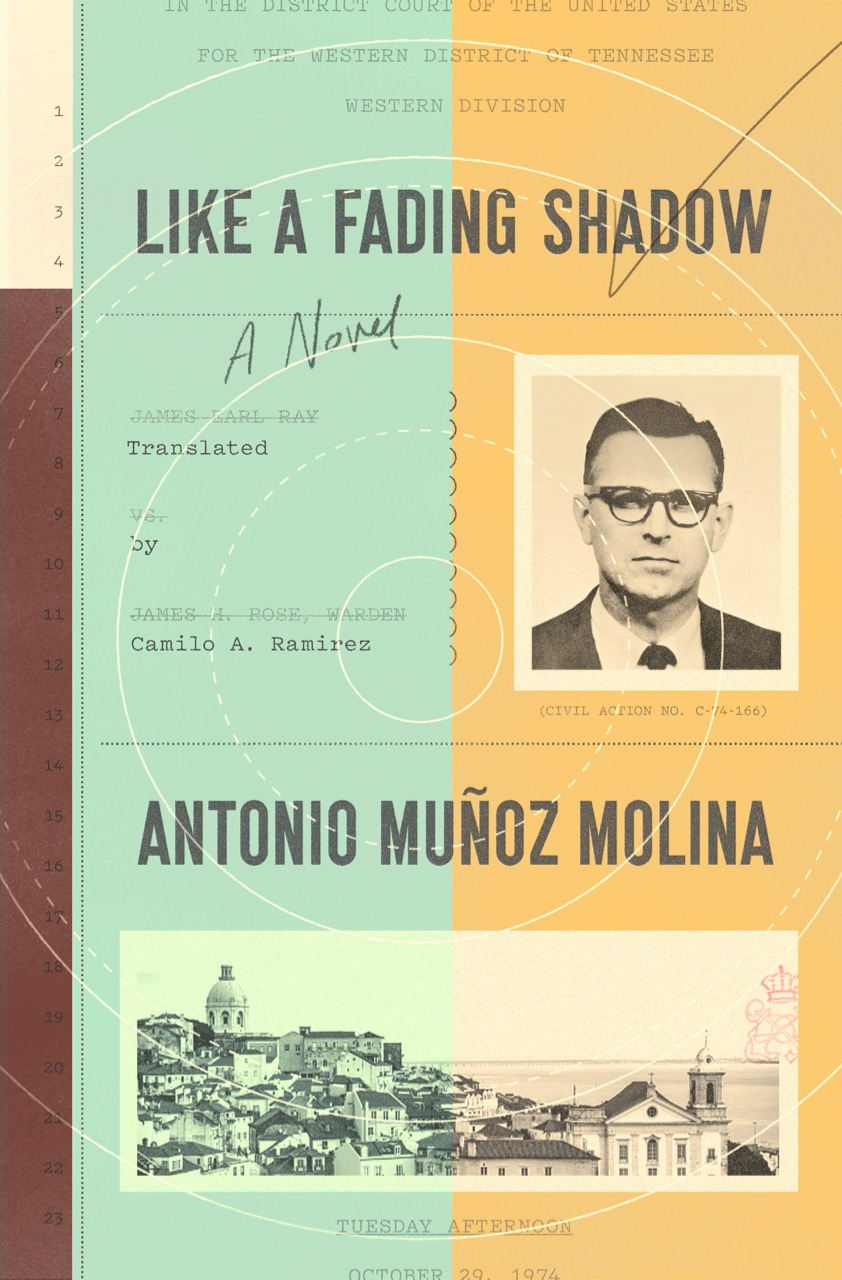

Like a Fading Shadow, by Antonio Muñoz Molina, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 312 pages, $27

• • •

Like a Fading Shadow is built out of two largely unalike stories that nevertheless illuminate each other. The first concerns a bizarre and rather minor episode following one of the most heinous political murders in American history, the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. by James Earl Ray. For ten days, Ray took cover in Lisbon, where he’d flown on a fake passport via London after making his way to Canada after the killing. The Portuguese city, he imagined, would permit him to slip away into a new identity and a new life, providing a point of departure for Angola or Rhodesia or South Africa, where he planned to become a white soldier of fortune.

The second is a more quotidian account of Antonio Muñoz Molina’s own initial encounter with Lisbon nearly two decades after Ray’s, a city that would alchemically appear as a setting for the author’s noirish novel about jazzmen abroad, Winter in Lisbon. Though that book capitalized on the dark side of the Portuguese city as an eccentric landing pad for the sketchy Americans who wind up there, much as it did for Ray, the memory of Muñoz Molina’s visit is more tender, almost bittersweet, a portrait of the artist as a young man. He recalls how Winter in Lisbon set him on his path to realizing his goals, allowing him to ditch both his bland government job in Granada and his identity—“a father and a husband, and also a foolish adolescent, an apprentice in the art of the novel, and a bureaucrat”—and become the writer he’d always hoped to be. In Lisbon, he seemed to lose and find himself at the same time.

The connection between these two stories is one of geographical serendipity, but the result is a fascinating book that lets its incongruities blossom into little bursts of philosophical rumination on the nature of writing, the quiddities of cities in fiction, and the conundrums of time in both life and the novel. Published in Spain in 2014 and translated by Camilo A. Ramirez, Like a Fading Shadow is the seventh of Muñoz Molina’s twenty-something works to appear in English, and here he ruminates from experience on the unique possibilities of the novel—“a warm interior where you seek refuge as you write, a cocoon that is woven from the inside, locking you within it, showing you the world outside through its translucent concavity.” For him, it is at once a confession and a hideout. He once thought literature was an exalted game of confected forms—tightly constructed marvels that opened and “ended like a drumroll”—giving order to a less than perfect world. His breakthrough as a writer occurred when he learned to see the novel’s aspirations differently, where the ideal was to provide a kind of “scale model” of the forms and processes of reality. He approvingly quotes Emily Dickinson: “Nature is a haunted house—but Art—a house that tries to be haunted.” You might call his transformation Learning from Lisbon.

In the years after his self-styled apprenticeship, Muñoz Molina has become one of the most fascinating Spanish writers working today, a novelistic counterpart to his more playfully ironic countryman Javier Marías (who also likes to ponder over the philosophical side of literature but is less given to the sort of obiter dicta sidebars that punctuate Like a Fading Shadow). Muñoz Molina is a master at recreating the past in all its tang and texture, from Franco’s Spain of the 1960s (A Manuscript of Ashes) to the exilic milieus of the Jewish diaspora (Sepharad). His last book to appear in English translation, the voluminous In the Night of Time, reincarnated the moment of 1936 and the Madrid and New York inhabited by a Gropius-like architect, Ignacio Abel. By contrast, Like a Fading Shadow is a practically lithe little creature, but if comparatively brief, its account of a different historical moment—the curious week and a half that Ray spent in Lisbon—is no less decisive.

The Lisbon of 1968 can seem as removed from the present as the Madrid of 1936. The former is a dark place of backstreets and alleyways behind sun-parched public squares. Off the harbor were the rough joints named for other “exotic” locales—Arizona Bar, California Bar, Niagara Bar, and Texas Bar, the signage of the last a glowing beacon in red neon alongside a cartoon cactus, and it was here where Ray spent time as his stash of money disappeared. At the Hotel Portugal, he passed time reading and rereading the handful of spy novels with lurid covers and titles like Tangier Assignment that he kept with him throughout his flight. He fantasized about his own Ian Fleming–like escape on one of those ships that daily arrived at and departed from the Lisbon harbor, the names of which (Jakarta, or Sofala, or Luanda) betrayed the colonial present. Muñoz Molina pictures Ray nauseated by the unfamiliar scents of the local cuisine but also struck by a somehow salubrious feeling of home prompted by the fetid waterfront. Lisbon smelled like St. Louis or New Orleans or, for that matter, Memphis.

When Ray discovered that his glorious future as an anti-anti-colonialist was blocked, he reversed course and flew back to London, his would-be escape turning in on itself. There, he was stopped when a customs officer spotted an error in his fake Canadian passport. Muñoz Molina rightly portrays Ray as the repulsive figure he was, a racist murderer who stank of Right Guard deodorant and pomade, who after his extradition pleaded guilty to avoid the electric chair, then recanted once he was given a ninety-nine-year sentence and began to peddle conspiracy stories involving a puppet master named Raoul. It is a measure of Muñoz Molina’s achievement to see a character as unappealing and downright baffling as Ray able to sustain attention over the course of the novel.

Muñoz Molina’s portrait works because his Lisbon is a place where identity gets slippery, for Ray as for the author in his early years. The city he discovers as a young writer is a kind of cinematic readymade, a projection as much of Muñoz Molina’s fantasies as much of his protean assassin, for whom it seems life itself was a very dark fantasy. This is one thing the two of them share. “Before thoughts can fully form, the secret novelist inside us all is already plotting stories,” the author writes at the beginning of the book, when he awakens in a dark room, unsure of where he is, exhausted and confused by his research into Ray. In Like a Fading Shadow it’s only the first of many moments where author and killer become bedfellows—strange, perhaps improbable, yet provocatively close.

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU. He is the former president of the National Book Critics Circle. He was previously editor-in-chief of Bookforum and a senior editor at Artforum.