Sarah Rifky

Sarah Rifky

At Bard, an exhibition of Arab art challenges its curatorial framing.

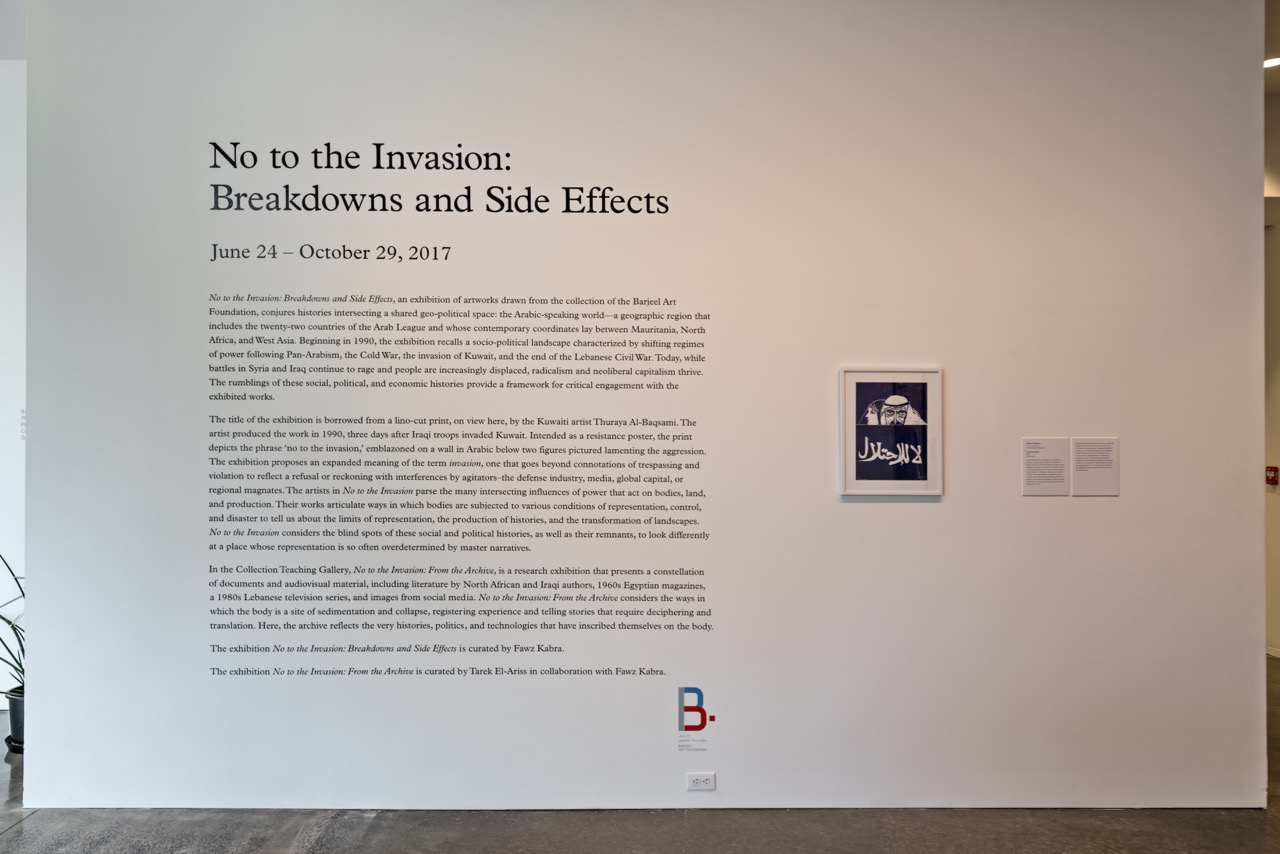

No to the Invasion: Breakdowns and Side Effects, installation view. Photo: Chris Kendall.

No to the Invasion: Breakdowns and Side Effects, CCS Bard Galleries, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, through October 29, 2017

• • •

No to the Invasion: Breakdowns and Side Effects is the latest in a tradition of shows that brokers art of the Arab world to a “Western” public. The exhibition is curated from the Barjeel Art Foundation, which holds the private collection of social media figure Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, and is involved in shaping and sponsoring a series of exhibitions, publications, and scholarly events that stake out the yet-to-be-written history of modern and contemporary Arab art. This canon building is part of a globally dynamic, multifarious, and intellectually contentious effort that has surged in the past two decades in tandem with the cultural upscaling and nation-building efforts of the Arab Gulf. No to the Invasion tries—not always successfully—to avoid the curatorial pitfall of geo-themed exposé museum shows that dogged two recent surveys of Arab art, the Guggenheim’s But a Storm Is Blowing from Paradise (2016) and the New Museum’s Here and Elsewhere (2014): that of essentializing the artworks being displayed by treating them as signifiers of place, as ethnographic objects. Still, the best things about No to the Invasion lie somewhat beyond its explicit intention of weaving a thematic exhibition on the notion of invasion—it is an exemplary space for scrutinizing how artworks subvert curatorial plots and a rare opportunity to leisurely engage with many research-based art projects of the Arab world.

The first work leading into the galleries is Thuraya Al-Baqsami’s La Lil Ihtilāl (1990), a rough linocut that protests Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. The print features two figures and a phrase that reads in rough Arabic lettering: “La Lil Ihtilāl.” The phrase glosses only imperfectly into the exhibition’s title—while No to the Invasion is also the given English name to Baqsami’s work, ihtilāl more accurately translates into occupation. The curatorial statement revolves around the notion of invasion in a loose sense, making heady claims about expressions of resistance against the so-called invasion of media and global capital and how these “might be refused.” The work introduces a dual leitmotif to the show, only one of which was curatorially intended. The figures in the print are of a man wearing a keffiyeh (a traditional Arab headdress) and a woman, in profile, wearing a stoical expression. The man stares straight at the spectator, while the woman’s eyes are fixed on the wall text. These varying gazes help create a triangulation of aesthetic object, didactic text, and viewer. Interrupting the curatorial storyline of “invasion,” this triangulation renders self-conscious both the institutional framing of the works on display and their relationship to Western audiences.

No to the Invasion: Breakdowns and Side Effects, installation view. Photo: Chris Kendall.

Toward the center of the first gallery stands Witness (2009), a miniature, white ceramic statue riddled with tiny little holes mimicking bullets marks. Created by Mona Hatoum, Witness pays homage to Beirut’s Martyrs’ Monument from the 1960s, which was badly damaged during the civil war (1975–90). Adjacent to Hatoum’s work is a single bar of soap engraved with the Arabic saying dawām al hāl min al mūhal (no condition is permanent). This work is a discrete installation by Taysir Batniji from 2014, yet it uncannily recalls a work that is not in the show, Hatoum’s Present Tense (1996), an installation of 2,400 olive oil soaps from Nablus (north of Jerusalem) and beads that form the 1993 map of Palestine following the Oslo Accords. The construction of present and absent monuments—present and absent artworks—evokes the craft that goes into constructing histories and the critical gaze Baqsami’s characters cast onto the exhibition’s premise and its beholders.

No to the Invasion: Breakdowns and Side Effects, installation view. Photo: Chris Kendall.

In the second gallery, one finds instances of humor that resist the earnestness of the encasing framework of “invasion.” Notably, several photographs from the series Autobiographies (1994), by Emirati conceptualist Mohammed Kazem, present the artist trying to force his tongue into objects (a keyhole, a thermos . . .), giving intrusion a comical spin. The third and fourth rooms showcase the greatest strength of the exhibition, with several research-based projects, including Jordanian artist Ala Younis’s Plan for Greater Baghdad (2015). The Plan is an elaborately composite presentation of drawings, prints, and 3-D printed figures, based on the artist’s extensive research into architectural monuments in Baghdad, utilizing the slide archive of Iraqi architect Rifat Chadirji. The archival display spans an entire wall and presents the telenovela-like history of a gymnasium designed by Le Corbusier in the 1950s that took decades to complete and was eventually named after Saddam Hussein. Younis’s project is a highly complex and imaginative historical account that involves many architects and politicians, actors and agents, and contains often amusing archival reports, imaginative renderings (there is a man wearing a Mickey Mouse costume shaking hands with a government official), and an emblematic Baghdad site (the gymnasium was where the US army was stationed following the fall of Baghdad and where 2014 parliamentary election rallies were held). Younis’s work—with its dry wit—complicates the possibility of picturing monuments and dictators, or notions of invasions or canons for that matter.

Sarah Rifky is a writer and curator. She is the co-founder of Beirut (2012–15), an art initiative and exhibition space in Cairo. She is the author of numerous essays of art and other speculative fiction. She is pursuing her PhD in History, Theory, and Criticism at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she is a fellow of the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture.