Thomas Beller

Thomas Beller

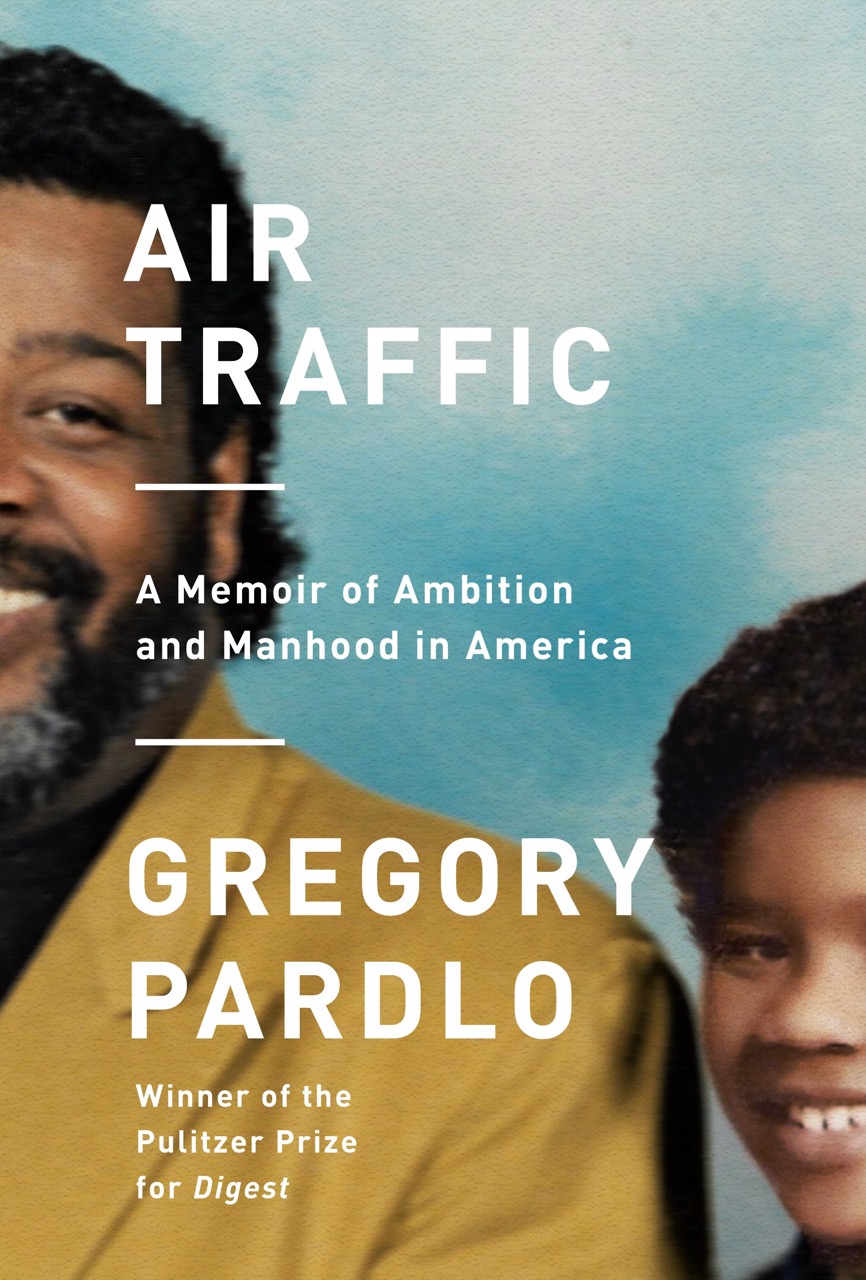

Put nothings between somethings: a family memoir by Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Gregory Pardlo.

Air Traffic: A Memoir of Ambition and Manhood in America, by Gregory Pardlo, Knopf, 253 pages, $26.95

• • •

Subtitles to works of nonfiction are an affliction particular to American publishing. They are not required in Britain and France, as far as I know. They always vaguely insult the intelligence of both reader and author. The subtitle to Gregory Pardlo’s Air Traffic is A Memoir of Ambition and Manhood in America. Sure, but it’s also a book involving race, class, addiction, mothers, simultaneous orgasms, and, perhaps most of all, inheritance. The title comes from the fact that both Pardlo’s father and maternal grandfather were air traffic controllers. Black air traffic controllers.

Air Traffic begins: “By some concoction of sugar, nicotine, prescription painkillers, rancor, and cocaine, my father, Gregory Pardlo, Sr., began killing himself after my parents separated in 2007.” Sr. died in 2016, just as the final draft of this book was being completed. “He lived his last years like a child with a handful of tokens at an arcade near closing time. Those tokens included: access to credit, the patience and generosity of his family and friends, and any saleable assets (including, possibly, the titanium urn that contained his mother’s ashes, mysteriously missing from the one-bedroom Las Vegas apartment where he chose to fizzle out).”

Such is Pardlo Jr.’s style—the syntax and thought process sinuous, elegant, the mood one of blunt disclosure. Writing from the vantage of middle age and fatherhood, he sees the giants of his youth, such as his father and grandfather, not through the awestruck eyes of a child, but in the context of history. The historian’s cool eye is the weapon with which he fights off the eulogist’s impulse to valorize his subjects. (He is also circumspect about the Pulitzer Prize he won for his 2014 poetry collection, Digest.) Of his maternal grandfather, among the first black air traffic controllers, he writes, “he was no superhero. His story is most unremarkable . . .” He points out that “before President Woodrow Wilson made segregation the law of the land, federal jobs supported many middle-class black families.”

Having announced his grandfather, Bob, as no superhero, he describes a plane landing in Oklahoma City, home of the Civil Aeronautics Administration, in 1951. The plane carries his grandfather and another black man, both to be trained as radio technicians. The arrival of these two black men had been announced in the papers. A crowd, as though assembled for a celebrity, greets them on the tarmac. In view of journalists and photographers a belligerent sheriff says, “I guess you know you’re in the South now, boys.” The pair are hustled into police cars and taken “to the one rooming house in town that would accept ‘colored’ guests: the local brothel.” One of the two men cracks under the unrelenting pressure of racism. The other, his grandfather, completes the course.

Bob guides his son-in-law, Gregory Pardlo, Sr., into the same profession. Thus Jr. has two generations of air traffic controllers as his patrimony, and Air Traffic has its title.

We learn, in this book, a bit about the history of American aviation and a bit about how Sr. thinks. By way of explaining the task of the controller to his son, he says: “More than anything else, the one rule that matters is spacing. The one true element of the universe: emptiness, incremental negations, putting nothings between somethings—that’s what makes order of the chaos.”

Sr. embodies a stoic pragmatism and the mysticism of a philosopher gambler who is living on the edge, complete with a messianic self-regard. The controller as god of all he sees. Sounds like a writer.

Pardlo’s mind has a natural tendency to situate the individual in the context of history, perhaps because history came and smacked his family directly in the face in the form of the 1981 air traffic control strike. President Reagan gave the controllers forty-eight hours to report to work or be fired. In issuing this threat, Pardlo writes, Reagan “legitimized termination as a response to labor disputes, dealing a critical blow to labor worldwide.”

Most, including Pardlo’s father, one of the strike’s leaders, did not return. They were not only fired, but banned from any employment with the federal government.

The blow to the family is immediate. The financial problem is, in a way, the most resolvable; the damage to his father’s self-esteem is the most lasting. It’s bracing to be at this fraught intersection of American history, Department of Race and Class, and the witty, erudite, badass exceptionalism of the Pardlo family. Pardlo is a poet, not a historian, and the book is structured not by chronology but by free association.

Air Traffic contains vignettes from childhood, including a magnificent episode in which he tracks down his stolen moped to a neighbor’s backyard, where he finds it partly disassembled. Next to the moped is a leashed Pomeranian, put out for the night, which he decides to kidnap. The plan is not to hurt the dog or even to ransom it, but to simply return it as though to somehow provoke remorse in the thieves.

“My self-image,” he writes, “was caught in a bitter custody battle between Alex P. Keaton and Jimi Hendrix.”

The book’s prose is often exhilarating—“I learned from my father that there was no glory in just winning. Capricious, pendular, my father’s wont was to sway by the rope of his devotions, to and fro, and winning was a one-way trip. What point was there in winning if that precluded the possibility of a comeback?”—but I gradually became uneasy with an absence I couldn’t quite name. There were glimpses of something hiding between the lines—the word “bipolar” flies by. The details of Pardlo’s marriage and parenting adventures feel, if not banal exactly, somehow evasive, a form of stalling. In the final chapter, “On Intervention,” what had been felt but not seen comes plainly into view.

The chapter title has multiple entendres. It is an essay on the nature of alcoholism (“Because it is eternal, alcoholism is the closest thing I have to religion”) and the nature of interventions; a rumination on the role of alcohol in his family (“Alcoholism was the Muzak of our familial dysfunction. Most of the time, we didn’t even notice it”); an account of the intervention staged for his younger brother Robbie (a real-life pop-star in the 1980s whose band, City High, was nominated for a Grammy); and, encompassing it all, an account of literally being on Intervention, the A&E reality television show, which sponsored and filmed the Pardlo family’s attempt at rescuing Robbie.

The family—mother, brother, Sr., and Jr.—all have their say in this last chapter, where the Chekhovian family tensions one felt were being suppressed elsewhere come into view. Sr. and Jr. have a confrontation that is both moving and, because a camera crew is trailing them down the hall, absurd.

One of the difficult things about this fascinating book is that the father, so flawed and infuriating, has so many great lines. Another is the feeling of absence in the prose itself, which never lacks in perception but often feels lacking in intimacy with the characters, including the character of Gregory Pardlo, Jr., once he is no longer a child. But then the difficulties of intimacy—of spacing, to put it in air traffic controller terms—are the book’s subject.

Thomas Beller is the author of four books, most recently J.D. Salinger: The Escape Artist, which won the 2015 New York City Book Award for biography/memoir. His fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, the St. Ann’s Review, Ploughshares, and the New Yorker. A founder and editor of Open City Magazine and Books from 1990 to 2010 and the website Mrbellersneighborhood.com, he is currently an associate professor at Tulane University.