Nico Israel

Nico Israel

The art of the meat cleaver: Raw Nerve surveys nearly sixty years of the painter’s work.

Leon Golub: Raw Nerve, installation view. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Leon Golub: Raw Nerve, the Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue,

New York City, through May 27, 2018

• • •

“The nightmare of history has no beginning and has no end.” Thus spake Leon Golub, according to a wall text in Raw Nerve, an exhibition surveying the late artist’s body of work. In making such a portentous declaration, Golub sounds a lot like James Joyce’s fictional young alter-ego Stephen Dedalus, who in the early pages of Ulysses asserts that “history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” Both Golub and Joyce drew on the myths and artistic legacy of ancient Greece and Rome in order to address the just-completed and impending wars and forms of colonial domination of their day that seemed a logical consequence of the bloody history of antiquity.

But while the Irishman Joyce, responding to the Great War and British imperialism, invented a new, comic literary form to confront the nightmare that ostensibly began with the Trojan War, the American Golub, decrying the Vietnam War and the US’s support of odious right-wing regimes in Latin America and South Africa, mined the tragic, making expressionistic, often monumental paintings that portray bloody bodies in battle along with other perpetrators and victims of extreme violence and torture. Golub’s signature technique was to outline figures of human bodies (or heads) on linen, fill them in with layers of acrylic paint, and then carve and scrape that paint away using a meat cleaver and other abrasive tools. In fact, given the gore and brutality on view, the blunt directness of his politics, and his insufficient attention to the dangers of aestheticizing violence, the meat cleaver becomes an apt emblem for the show.

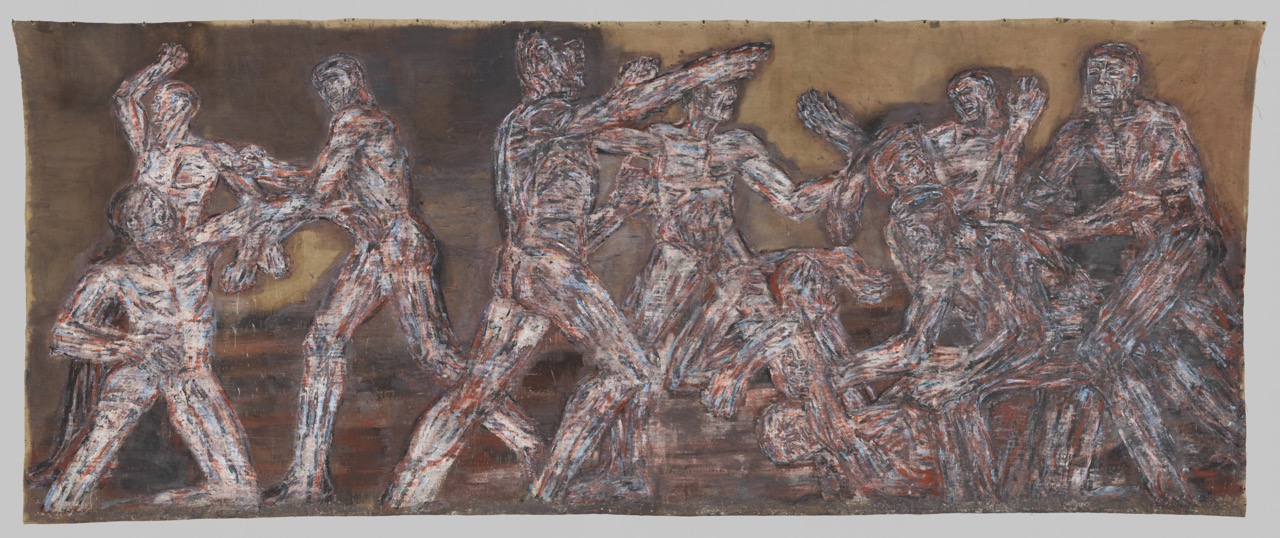

Leon Golub, Gigantomachy II, 1966. Acrylic on linen, 9 feet 11 ½ inches × 24 feet 10 ½ inches. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts, licensed by VAGA.

The occasion for the exhibition of forty-four artworks created between 1947 and 2004 was the gift, in 2016, to the Metropolitan Museum by Golub’s wife, artist Nancy Spero, and their children, of the twenty-five by ten-foot painting Gigantomachy II (1966), depicting a group of ten male nudes engaged in a nightmarish Matissean dance of hand-to-hand combat. The painting’s primary reference is the frieze on the base of the magisterial Pergamon Altar, which represents the battle of the Olympian gods against a race of Earth-born Giants. The second-century BCE altar, created in part to celebrate Pergamene victories over various “Barbarian” tribes, was shipped away from the disappearing Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century to a newly powerful Germany and housed at the Pergamon museum in Berlin (which was completed in 1930, less than three years before the philhellene Hitler’s rise to power). Perhaps these accumulating narratives of battle and domination interested Golub, and he viewed their histories of victory and, especially, defeat as in some way embedded in his acrylic and linen. But the absence in his painting of any distinguishing features of either Olympians (which in the original frieze were beautifully sculpted, of both sexes, and clothed and winged) or Giants, and the emphasis on the scraped-out paint that expresses the warriors’ exteriors as flayed skin and their interiors as “raw nerves,” generalizes—indeed universalizes—the battle.

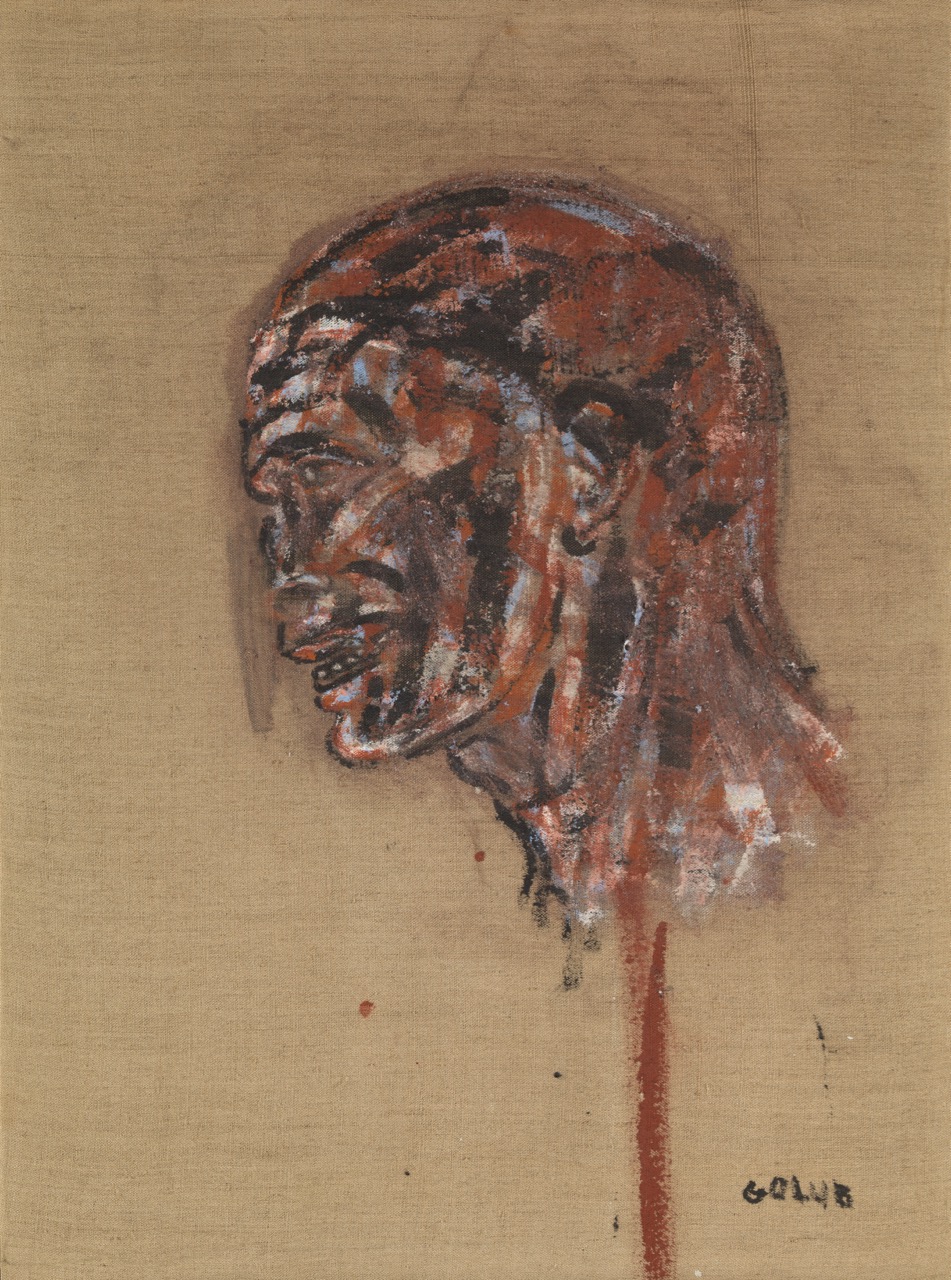

Leon Golub, Vietnamese Head, 1970. Acrylic on linen, 24 × 18 inches. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts, licensed by VAGA.

By the late 1960s, Golub—who had (laudably) joined the anti-Vietnam War activist group Artists and Writers Protest—was making his commitments and references more explicit. In Vietnamese Head (1970), at twenty-four by eighteen inches one of the smallest paintings in the show but also one of its most powerful, Golub exhibits a head that has been severed and mounted on a pike; the figure’s face has ill-defined features but seems to be grimacing in pain and fear, as though registering the moment of decapitation. The condensed expressionistic work intends to denounce US and South Vietnamese brutality and to sympathize with the victims of imperialism’s callous cruelty, but one can’t help wondering whether picturing that mutilated head in such agonized detail doesn’t verge on aestheticizing what it aims to de-aestheticize, thereby participating in the very violence it is condemning.

Leon Golub, Pylon V (Napalm Gate Fragment), 1970. Acrylic on linen, 108 × 28 inches. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts, licensed by VAGA.

Pylon V (Napalm Gate Fragment), also from 1970, brings together Golub’s fascination with both classical civilizations and modern warfare. To make this work, Golub took pieces of unprimed canvas from some of his unfinished paintings and shaped them into a pylon, the Greek word for a large gateway into an ancient city or temple. Pocked with red oxide paint, the pylon, which Golub mounted directly on the wall, looks like it was violently disfigured by residue from the nefarious defoliating agent-cum-skin searing weapon. This kind of exploration of the possibilities and implications of color and sculptural form is typically relegated to the backgrounds of Golub’s representational paintings, but points to an interesting road not taken by the artist.

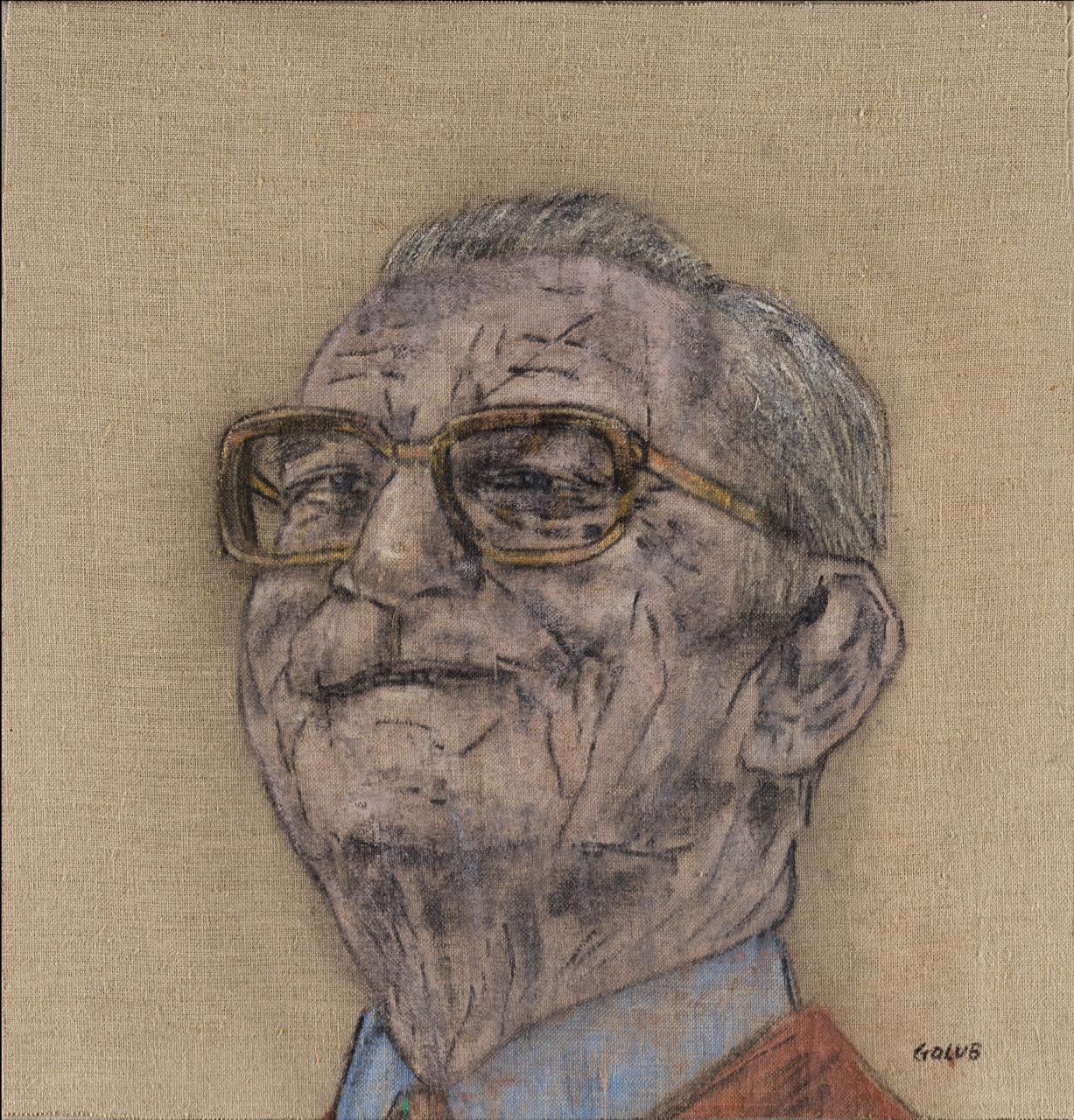

Leon Golub, General Ernesto Geisel (1976), 1977. Acrylic on linen, 19 ¾ × 19 × 1 inches. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts, licensed by VAGA.

Instead, Golub moved toward portraying heads of the leaders of authoritarian regimes (a series of portraits of Brazilian dictator General Ernesto Geisel looking surprisingly benign and vulnerable), scenes of torture in Central America (a man hanging from his feet being kicked by a soldier), tableaus featuring South African mercenaries, and apparently everyday scenes such as that of a white man standing by two seated black women in a park, their glances never meeting, with the white man’s expression exuding a kind of menace; the last work is part of a series investigating the role of bystanders to atrocities. Besides late Roman and other classical influences, additional material Golub drew on in creating the canvases came from his “photographic archive” of sports magazines, sadomasochistic porn, and Soldiers of Fortune. These large-scale, passionately painted works demonstrate that there is a fine line not only between eroticism and violence, but between inveighing against toxic masculinity and, through complete immersion, unwittingly participating in it.

Leon Golub: Raw Nerve, installation view. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

According to curator Kelly Baum, Golub’s “unflinching portrayals of power and violence have much to teach us in the twenty-first century, as does his belief in the ethical responsibility of the artist.” Certainly Golub had “raw nerve” and tenacity, and he no doubt cared deeply about human suffering. Yet his critique of power and violence consisted of confronting slaughter by representing slaughter, and trying to work through the effects of power by manipulating paint. Whether this amounts to a genuinely ethical response to the nightmare of historical inheritance and ongoing tyranny and bloodshed is an open question.

Nico Israel is a professor of English at the CUNY Graduate Center and Hunter College. His latest book, Spirals: The Whirled Image in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art (Columbia UP), has recently come out in paperback. He has published numerous articles on modernist and contemporary literature and literary theory, and over seventy-five essays on contemporary visual art, many of them for Artforum.