Thomas Beller

Thomas Beller

Back down from the shelf: Vivian Gornick revisits ten books.

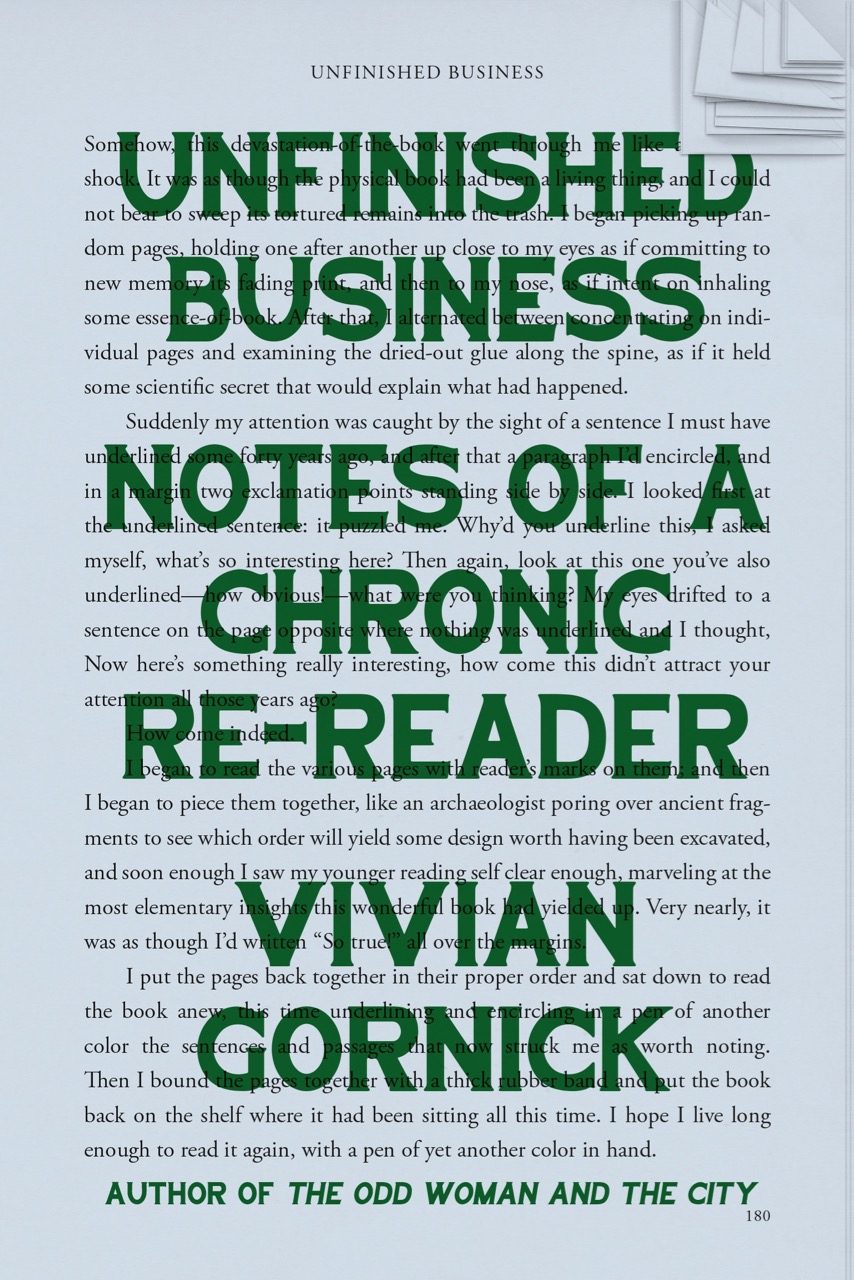

Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-reader, by Vivian Gornick, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 161 pages, $25

• • •

When I was almost done with Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-reader, Vivian Gornick’s enchanting and addictive little book—whose size and shape make it feel like it contains epigrams and instructions for life when in fact it contains not so much instructions for life, but life itself—I went to the library in search of Gornick’s other works. She made the act of rereading so appealing I wanted to reread her. Her work—biography, the personal essay, history, a how-to book for writers, memoir, usually in some combination, always in a distinctive personal voice—was strewn around on different floors.

Like some of her other books, Unfinished Business takes up literary criticism in Gornick’s distinctly participatory way; putting the “ ‘personal’ and the ‘journalism’ together proportionally,” as she says her introduction. Each of the book’s ten short essays functions as a reunion with a work of literature that had been important to Gornick earlier in her life. They also function as reencounters with the former self who read them long ago.

The first book she considers is D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers. Gornick locates herself as part of that 1950s generation of girls “joined at the hip to those restraints of bourgeois life that kept erotic experience at a distance. This distance fed a dream of transcendence linked to a promise of self-discovery interwoven with the force of sexual passion. Only then we didn’t call it passion, we called it love.”

She and her generation imbibed Sons and Lovers, and Madame Bovary, and The Age of Innocence, and Anna Karenina, “as well as the ten thousand middlebrow versions of those books,” which confirmed that “to know oneself through the senses was to arrive at the heart of human existence.”

Rereading the novel now, she sees it in a markedly different light. “How it had escaped me that the characters in Sons and Lovers are themselves deeply embittered over the consequences of a life posited on sexual passion.” Mrs. Morel, while pregnant with Paul, the son of the title, looks ahead to her life and feels “ ‘buried alive.’ Why buried alive? Because,” writes Gornick, “encased as she is in spiritual loneliness, she is drowning in dissociation. ‘What have I to do with it?’ she said to herself. ‘What have I to do with all this? Even the child I am going to have! It doesn’t seem as if I were taken into account.’ ”

“This was a speech I did not at all recall,” writes Gornick. What read as a manifesto on behalf of sensual experience when she was younger now seemed like a devastating anatomy of how disappointment and loneliness function within a marriage—a richer and more nuanced work of art.

The Lawrence chapter is followed by one on Colette, and then one on Marguerite Duras’s The Lover. As one might gather from these titles, love, lust, obsession, and their discontent and delusions are a preoccupation.

Gornick’s critical perceptions are often rooted in her lived experience. About the affair at the center of the book, she writes: “The narrating voice in The Lover actually replicates the narcotic lull of desire itself,” while at the same time, “somewhere inside that voice can also be heard the sorrowing sound of one who is using desire to avoid rather than to illuminate. But now, thirty years after the book’s publication,” when she first read it, “it was to this sound—the sound of avoidance—that I found myself resonating.”

Not all the chapters are as postcoital in mood, and not all are about books I have read. I was unfamiliar with Elizabeth Bowen’s novels, “whose power,” Gornick writes, “I felt when I was young, but whose value I did not grasp until I was old.” She “gulped down” Bowen’s three major works—The Death of the Heart, The House in Paris, The Heat of the Day—“and then never looked at another word she wrote.” Then a remark by Adrienne Rich about Emily Dickinson—“there are extreme psychological states that can be hunted down with language. But that language had to be forged—found; made—it was not the first words that came to mind”—sent her “forcibly, and suddenly” to her bookshelf to pick up Bowen’s work.

This chapter is the most biographical in its approach. Bowen wrote of her own orphanhood that it was “the beginning of a career of withstood emotion.” “From here on in,” writes Gornick, “she—like most of her characters—would become an intimate of ‘life with the lid on.’ ” A terrific turn of phrase that leaves me eager to read Bowen, and makes me experience Gornick anew: a voice with the lid mostly off.

Gornick reads The Death of the Heart, with its distinctly English sadism of withheld emotions, through a prism of both her own experience and Bowen’s life. Bowen fell “deeply and irrevocably” in love with an emotionally aloof man named Charles Ritchie in 1941, in the middle of the London Blitz. As with Bowen herself, there was within Ritchie “a vast emptiness which he, too, medicated with sensation . . . each had recognized something crucial about themselves in the other—the disfiguring power of ‘withstood emotion’—and longed for rescue from its arid fate.”

Delmore Schwartz, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Natalia Ginzburg, and Thomas Hardy (the one nineteenth-century author present)—all are reexperienced in the same lucid, mercilessly penetrating way.

The book ends with a brief, pithy piece about the act of rereading itself. It doesn’t specify a title or author, just alludes to a “cheap 1970s paperback.” It describes the sensation Gornick felt when seeing a sentence that she “must have underlined some forty years ago” in colored pen. The book’s binding is so brittle that pages fall off. As she reads and underlines, now with a different colored pen, they fall around her like leaves. Then she reassembles them, binds them with a rubber band, and puts the book back on the shelf, imagining another visitation in the future.

It’s the least intense piece in the book, as though Gornick didn’t want the reader to get the bends rushing up to the surface of daily life from the pressurized intensity of her earlier chapters. It’s a perfectly fine way to wrap up Unfinished Business.

As a finale, though, I prefer the brief note that opens the book, in which the author explains that some of its passages appeared previously in other writings. “I have felt free to ‘plagiarize’ myself . . . precisely because my subject here is re-reading.” She concludes the note, “I sincerely hope the reader will not find this practice off-putting.”

Not at all. The pleasure was mine.

Thomas Beller is the author of four books, most recently J. D. Salinger: The Escape Artist, which won the 2015 New York City Book Award for biography/memoir. His fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, the St. Ann’s Review, Ploughshares, and the New Yorker. A founder and editor of Open City Magazine and Books from 1990 to 2010 and the website Mrbellersneighborhood.com, he is currently an associate professor at Tulane University.