Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Dalí patches, Lichtenstein riffs: a show gathers the artist’s

embroidered paintings.

Nicolas Moufarrege, Le sang du phénix, 1975 (detail). Thread and pigment on needlepoint canvas, 50 × 64 inches. Photo: Hai Zhang.

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, curated by Dean Daderko, Queens Museum, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, New York City, through February 16, 2020

• • •

The life story of artist, writer, and “poet philosopher” Nicolas Moufarrege is cinematic in its scope and vicissitudes. He spent his nearly four decades on earth moving from one artistic capital to another, quaffing those cities’ headiest days and then leaving, whether because their welcome soured or to escape their inevitable, ruinous desiccation. Along the way, he made beautiful images often inspired by the visual matter around him. Recognize My Sign, at the Queens Museum, presents thirty-seven of his deliriously gorgeous embroideries, works described by his close friend, poet Rene Ricard, as “the Veuve Cliquot of painting.” In Moufarrege’s lifetime, his art was overshadowed by his role as a critic and curator who, in the early 1980s, helped give the ebullient scene of New York City’s Lower East Side its discursive contours. Recognize My Sign, his first museum survey, restores his effervescent, roborant artworks as central to his legacy.

The show’s curator, Dean Daderko, takes a memoirist’s approach to the material, which is organized chronologically and by place. Critic Kaelen Wilson-Goldie evocatively narrates Moufarrege’s peripatetic biography in an accompanying publication, describing how the artist was born in Alexandria in 1947 to Lebanese immigrants, during the coastal city’s most glorious epoch, the one immortalized by Lawrence Durrell in his iconic quartet of novels. When Moufarrege was five, Egypt’s monarchy was felled, and Alexandria began to transform; worried about their future, Moufarrege’s parents sent their son back to Lebanon in 1961, to a boarding school near Beirut.

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, installation view. Image courtesy Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang.

As Alexandria’s status as a cosmopolitan metropolis was waning, Beirut’s was blossoming: Moufarrege grew up in a richly diverse city that was a hotbed of cultural activity. He didn’t immediately take to the arts, though, instead pursuing chemistry at college. The first works encountered in Recognize My Sign were actually made in the US—in 1968 he was awarded a Fulbright to do his MA at Harvard. In a 1973 interview with Etel Adnan, Moufarrege explained that one day in Cambridge he got a hole in his blue jeans and sewed a strawberry patch to cover it. Then he decided to make another patch, based on a favorite Salvador Dalí lithograph of a flower sprouting butterflies from its stem. From there he began needling small embroideries for friends. Such patches and little scraps greet the viewer upon entering the gallery, placed on a table under glass; the fragile psychedelic fancies presage the conceptually sophisticated work to come.

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, installation view. Image courtesy Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang.

By the time he got back to Beirut, Moufarrege began to think of himself as properly an artist, his embroideries as “experimental weavings.” At the Queens Museum, three lap-sized pieces representing this period are dark and densely stitched, almost sculptural; they’re filled with mysterious buildings and surreal symbols: dreamy visages and floating moons. Moufarrege was showing these tapestries in unlikely spaces (a restaurant, a furniture showroom), and he also took a job working at the front desk of Triad Condas gallery, which quickly offered him a solo exhibition in 1973. But he wouldn’t be able to capitalize on this burgeoning success—at least not in Beirut. Lebanon’s traumatic, protracted civil war was beginning to smolder, and he decamped for Paris in 1975.

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, installation view. Image courtesy Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang.

The works from the Paris years bubble with references to the baroque and neoclassical paintings he admired in the city’s museums (landscapes by Claude Lorraine, nudes by Peter Paul Rubens). He would find postcards and illustrated plates in books that reproduced his favorite paintings, photocopy them, and draw over them to create stark outlines, then transfer them onto needlepoint canvas. By now he thought of these pieces as paintings; parts of the compositions were totally improvised, some sections painted on with a brush; he began to incorporate negative space. The canvases got larger, too, stretched out on wooden frames.

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, installation view. Image courtesy Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang. Pictured: The Fifth Day, 1980.

Le sang du phénix (1975) feels like a bridge between Beirut and Paris. The surrealist imagery continues with a flock of eyes schizophrenically hovering in front of fragmented Ionic columns; a cypress tree in the upper-right corner and a clenched fist in the lower left allude to the violence in Lebanon. By 1980, though, works like The Fifth Day announce a maturer style. In the foreground, a nude figure twists back, muscles rippling, as he prepares to sling a stone to the sky (the body is based on a Marcantonio Raimondi engraving, itself a copy of an unfinished Michelangelo cartoon). Strapping male torsos, gracefully erotic, begin to populate Moufarrege’s images from here on out. He mixes in a pattern inspired by Islamic tilework on the bottom of the canvas; the enigmatic numbers “3 7 1 2” are stitched at the top; these elements will show up again and again. Phrases in Arabic will likewise ensue, especially the Arabic word for “yes,” whose letters are also his initials (NAM).

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, installation view. Image courtesy Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang.

Moufarrege stayed in Paris for just a few years—though he was showing in more established commercial galleries now, he was broke, and had trouble with the immigration authorities (late-’70s France was marred by a brutal tide of xenophobia). He moved on again, arriving in New York City in 1981, where he lived on St. Marks Place in the Lower East Side, just in time for that scene’s apotheosis. In New York, Moufarrege started to take the ’80s predilection for appropriation to new levels, appropriating already-appropriated images to create antic, associative pictures of his own. There’s a suite of works on view that comically rip off Roy Lichtenstein, pairing that artist’s panels (already ripped off from DC Comics) with other iconic art historical images (by Yves Klein, Edvard Munch, Hokusai), all arranged in Mondrian-like blocks of painted color. And Moufarrege was incorporating more particularly American iconography: the Empire State Building shimmers in metallic thread in one small canvas that nods to Andy Warhol’s film of the same name; other, frieze-like bands are populated by characters such as a cartoonish Santa Claus or the Statue of Liberty, as well as Spiderman, who Moufarrege declared his avatar.

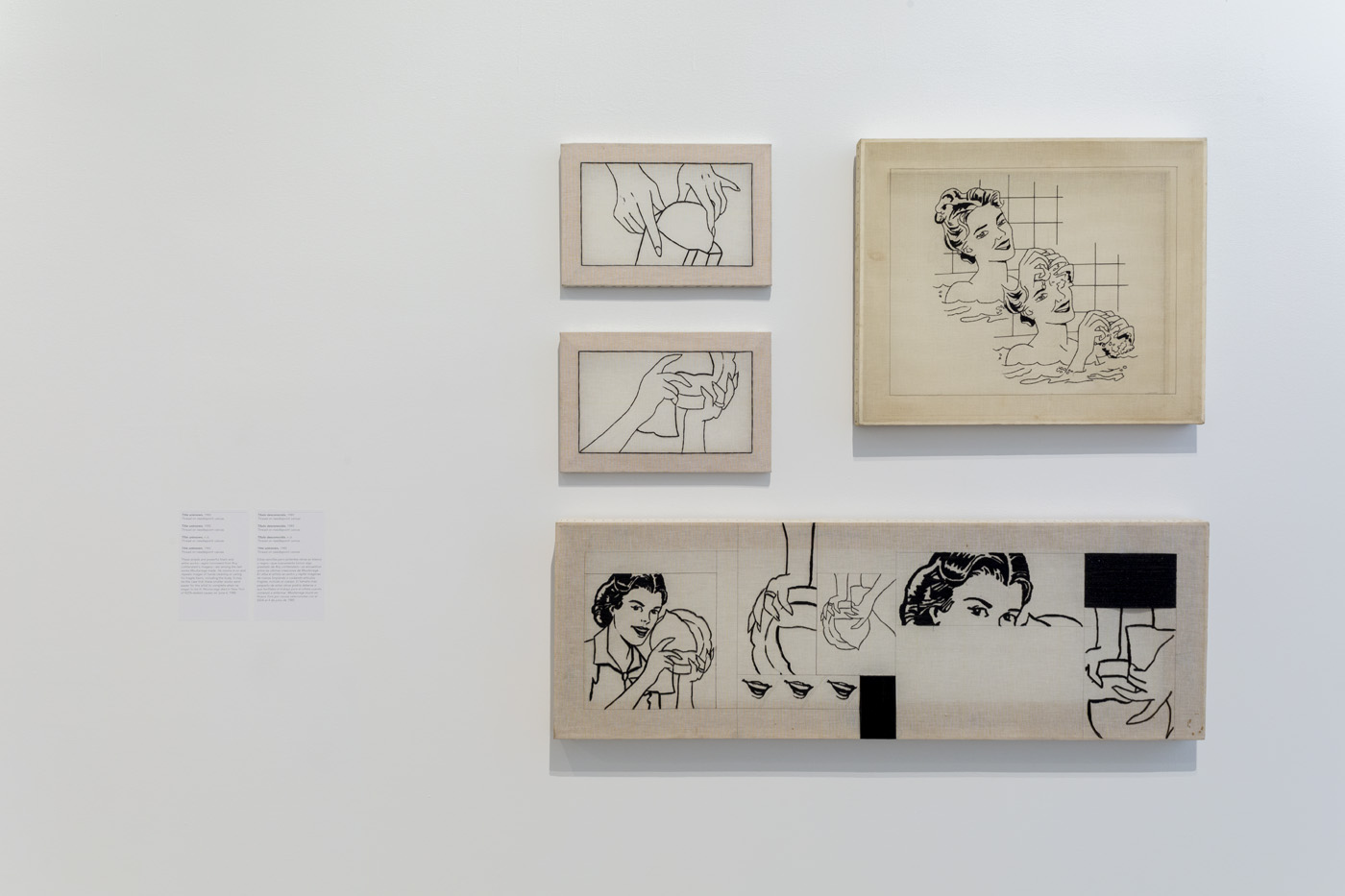

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, installation view. Image courtesy Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang. Pictured, bottom: Narcissix of One and Nick’s of the Other, 1983.

The show ends with four of the last pieces Moufarrege made, in 1985: commanding black-and-white embroideries also based on Lichtenstein’s art, but this time isolating out fragments of women cleaning—efficient, austere outlines depict hands washing dishes, squeezing a sponge in the bath. He was preparing for a solo show at FUN Gallery—it was his greatest dream to exhibit there, Ricard wrote, to join the ranks of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Fab 5 Freddy. Moufarrage was too ill to attend the opening, and died on June 4, 1985, at the age of thirty-seven, of complications due to AIDS. His was one of the first cases in New York City—he struggled to find a hospital to take him in, and was mistreated in the one that finally did. “I went to the opening, Nicky,” Ricard wrote in the artist’s Village Voice obituary. “It was a smash. All of New York is clamoring for your work.”

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, installation view. Image courtesy Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang.

“Exile is an ocean of chaotic information . . . One must transform the information whizzing around into meaningful messages, to make it livable,” Czech philosopher Vilém Flusser wrote in 1984. Like Flusser, Moufarrege lived a life of ceaseless motion, losing worlds he loved but always turning forward to new ones, needling the information whizzing around him into pictures brimming with vivacity, humor, sensuality, play. “There are times when I want to tell you of my pains, times of my joys, and other times when all I want is that you be there,” he once wrote. Follow My Sign lets us be there; and it lets his work live anew, rescued from memory’s faulty, dissolving maneuvers.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns.