Hannah Black

Hannah Black

A new version of the photographer’s 1972 exhibition resurfaces questions of exploitation, representation, and class alienation.

Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited, installation view. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited, David Zwirner, 537 West Twentieth Street, New York City, through October 22, 2022

• • •

Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited, now on view at David Zwirner, begins with the original show’s critical reception. Incendiary excerpts from reviews decorate the lobby. Many express open dislike for Arbus’s work, the selected quotes evincing revulsion masquerading as fake ethics. It’s often unclear if the writers imagined themselves siding with Arbus’s exploited subjects against her (“Who wants to be a freak at the Museum of Modern Art?”) or were mad at Arbus for confronting them with these repellent oddities in the first place (“They are losers almost to a man.”). If we thought our era invented aesthetic criticism on the grounds of morality, this rehashing of a long-ago, still-fresh tussle over the meaning of representation invites us to think again. When it comes to “freaks”—which mostly seems to have meant people who are queer, disabled, and/or of color—the ostensibly autonomous institutions of art give themselves over, luxuriously and resentfully, to social questions.

Diane Arbus, Woman in a rose hat, N.Y.C. 1966. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

Arbus’s photographs radiate intensity. She is attracted to heavy, definite faces swollen with self, or she makes all faces look like that. She likes the accoutrements of femininity: big hair, plucked and filled-in brows, lacy straps digging into thighs; relatedly, she enjoys masks, quirky eyewear, and gentlemen in hats. There are circus performers backstage in billowing outfits and nudists pleased to expose pale flesh—and, as if the dialectic of revelation and concealment, artifice and nature, wasn’t clear enough already, there are photographs of objects to emphasize it: a bedazzled Christmas tree pushing up at a cramped ceiling, a Potemkin house amid unkempt grass. When indoors, figures often seem overwhelmed by their own habitations; when outside, they are allowed to blur against ocean, fog, or forest. Sometimes her subjects stare down her camera with the defiance of documented savages, and sometimes they seem to bring themselves, for her, to the surface of their skin.

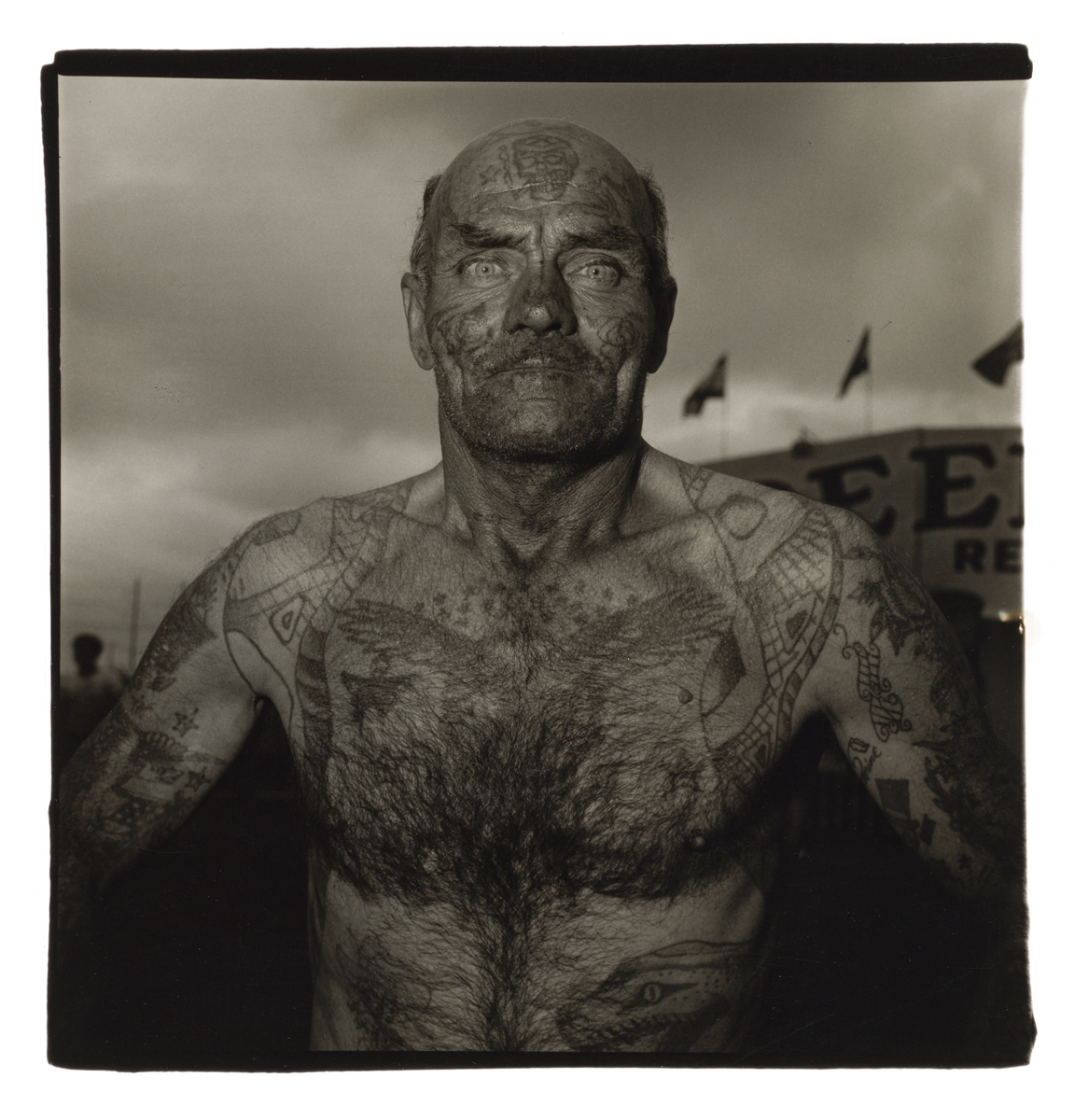

Diane Arbus, Tattooed man at a carnival, MD. 1970. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

With time, taken as one body of work, these have become an image of an era, and as such they seem to depict an age in which the distressed animal that thrashes at the edges of a mechanized, commodified society had yet to be engulfed by its simulacra. Arbus’s famous taste for ugliness reads as a refusal to contribute to this subsumption, a process that works by making the body look sleek and palatable. “How indefatigable everyone is,” she writes in 1960, referring to the resistance of New York’s homeless population to municipal harassment. In some ways, her time now looks kinder than ours: multiple, often strikingly joyful portraits of disabled people, especially those with Down syndrome, serve as an uncomfortable reminder of the current medical establishment’s eugenicist program of eradication.

Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited, installation view. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

Arbus’s contemporaries also aspired to depict the jagged theater of city streets, for example, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, whom Arbus showed alongside in MoMA’s New Documents exhibition of 1967. As a woman, as someone with a vivid relation to the world, Arbus too eagerly revealed herself. “I’ve been exploring, daring, doing things I’d fantasized about in my sheltered childhood,” she told Newsweek in 1967. From the perspective of this evergreen childhood fantasy, “there’s a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands you answer a riddle.” Positioned thus, her subjects take their place in the long lineage of depictions of the grotesque, a line originating before modernity, though altered by its development along with everything else. Never domesticated by its ubiquity, the grotesque is a kind of open wound that art is magnetized by and can never fully assimilate. In her guileless self-description, Arbus takes on a no-less-traditional role, that of the bourgeois adventurer who goes to the underworld to test her boundaries and in the process draws the outer contour of her own class position.

Diane Arbus, Four people at a gallery opening, N.Y.C. 1968. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

Photography is in fact something super traditional for Arbus: a mortification of the hubris of painting. As a young artist she was admired by her family and teachers as a promising painter, her talent carefully cultivated in progressive schools. But she believed her paintings to be in some way lifeless because they were purely the creation of her imagination. Like the world of her youth, the paintings’ very proficiency offered up only the image of a bloated self-regard. She needed to make a hole, an aperture.

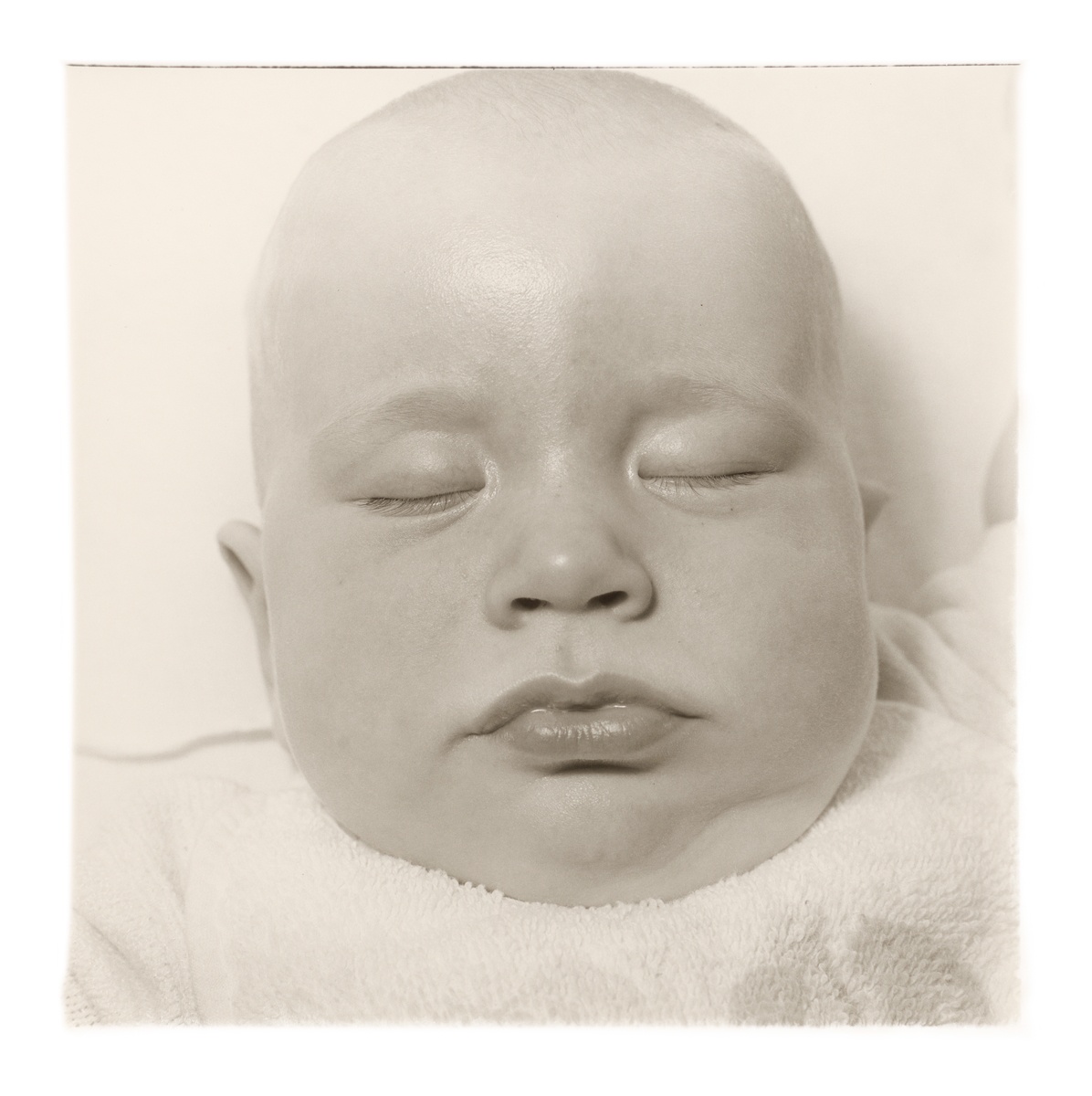

Diane Arbus, A very young baby, N.Y.C. [Anderson Hays Cooper] 1968. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

In a 1960 postcard to her friend and lover Marvin Israel, Diane Arbus writes, “Our bourgeois heritage seems to me glorious as any stigma, especially to see it reflected back and forth in the mirror of each other . . . It is magic, and magic chooses any guise and ours is just perhaps more hilarious than to have been Negro or midget.” It is funny, from some points of view, to be a member of a class that draws its basic identity from its good taste—i.e., excellent shopping habits—and delicate maneuvering around the specter of social, sexual, or financial embarrassment. These maneuvers are motivated by the problem of class itself, along with all the other social categorizations (race, gender, ability, etc.) that class famously mobilizes. Subcultures are either proletarian or they are just sclerotic relics. Recognizing this, Arbus slummed it from a titivating distance. In her photographs, the lives of the “Negro or midget” are a “glorious . . . stigma” that points beyond any specific shame falsely accruing to race or stature. The portraits aim to depict a subterranean shared condition, the poor freaks of color and the depressed bourgeois photographer forged by the same scar tissue. The shared magic therein is the magic of little gasps of life in a dead world.

Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited, installation view. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

By her own account, Arbus couldn’t figure out how to photograph orgies she participated in, judging the results as lacking in eroticism. Her own desire eluded her, aesthetically at least, without the stimulation of alienation and objectless longing. Her photographs are the self-portrait she could not produce in her own image, made up of the negative space surrounding her class position: the gender outlaws, the blacks, the failed women, the flesh oozing out from around the borders of propriety. These portraits of “Negros and midgets” present a familiar form of tourism at the thrilling edges of respectability. But they also depict the stigmata of the stupid, parasitic nature of Arbus’s small world of origin. Not all self-irony strives tirelessly toward a horizon of possible meaning, but hers did.

Diane Arbus, Triplets in their bedroom, N.J. 1963. © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

If I hadn’t been chastened by the idiotic-sounding critics on the wall at Zwirner, if I wanted to be unkind, I could draw a clear line from Arbus to the inanities of something like early 2000s Vice magazine, with its comparable attachment to pointing at freaks from a safe distance. But Arbus’s search for truth in images was sincere. She was capable, to the point of ill health, of self-criticism. She left an extraordinary oeuvre, not because she rescued freaks and minorities from obscurity but because she honestly portrayed her own complicated desire for access to a more alive-seeming realm of freaks and minorities. No wonder Los Angeles and San Francisco made her deeply homesick: the freak-spotting disposition is distinctively part of the history of white bourgeois New York City, where those who are into it have ample opportunity to play with the borders of their comfortable class position or spectate from it in a form of social safari. I could froth my fascinated resentment of this structural aspect of urban life into a political point: undeniably, this is a form of aesthetic primitive accumulation, making new terrains of existence available for valorization via the art system. But, for all their exaggerated ugliness, their dorky gawking at ordinary life, Arbus’s portraits express real admiration and care for all that she knows she cannot be.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer from the UK. She lives in New York. She has previously written for Artforum, the New Inquiry, and a number of other publications. Recent exhibitions include Wheel of Fortune at ETH in Zurich and The Meaning of Life at York University Gallery in Toronto. Her novella Tuesday or September or the End was published this year.