Hannah Black

Hannah Black

Lewis’s new dance explores blackness and the black box.

Ligia Lewis’s minor matter. Image courtesy Hebbel am Ufer. Photo: Dorothea Tuch.

Ligia Lewis: minor matter, Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin, November 24–27, 2016

Upcoming performance: Abrons Art Center, 466 Grand Street, New York City, January 8–10, 2017

• • •

Ligia Lewis’s electrifying new dance minor matter is the second in a planned triptych of pieces. The first was Sorrow Swag (2015), a solo saturated in the color blue and danced by a white man, onto whom Lewis transposed choreography she originally created using her own black body. In the red-hued minor matter, three figures—Lewis, Jonathan Gonzalez, and Hector Thami Manekehla—perform a complicated entanglement with one another, with blackness, and with the black box of the theater itself.

The work begins with Lewis’s voice speaking from darkness as the lights fade up with disorienting slowness. Her voice is threatening, seductive, and faintly absurd: “I want to turn you inside out and step into your skin.” It ends, in a stunning coda, with Lewis balanced in a half-desperate and half-playful embrace with the other two dancers, apparently about to fall, calling: “Black! Black!” This standard theater shorthand for “lights off” is the only direct verbal reference to the work’s central concern, here collapsed into the absence of light that marks the edge of performance, as the instruction “fade to black” marks the end of a scene in a screenplay. The ending retrospectively reveals the beginning’s meaning; the body being turned inside out is the body of the theater itself, which Lewis’s choreography has stretched to its limit in the intervening hour.

minor matter describes the boundaries of the theater as a means of arriving at the boundaries of being, which is to say, on the political questions of how black and blackened lives move through worlds or get fixed in place. The black box and black people are blurred into one, becoming the “minor matter” of the title, a necessary substance—the liberating neutrality of space or flesh—held in common and taken for granted.

I saw minor matter at the Hebbel am Ufer in Berlin (full disclosure: I participated in a post-performance panel, for which I received an honorarium). It was not long after the US election. This happenstance imbued the work with a new urgency, something not lost on Lewis, who is Dominican-American. It turns out utopia is going to have to coexist with apocalypse, and that both have been with us all along. Lewis’s work offers a kind of oblique blueprint for how joy, hope, anger, and despair are all always the case, using the paradigmatic fact of blackness. In black collective being, apocalyptic hurt and utopian community are folded together, which is what makes blackness, of late and since forever, so interesting to its others.

Ligia Lewis’s minor matter. Image courtesy Hebbel am Ufer. Photo: Martha Glenn.

At the work’s energetic peak, there’s a wild trio based on Maurice Béjart’s famous Bolero (1960), using the same sweeping arm gestures and steady rhythmic footwork as the original. While Béjart’s choreography has a solo woman surrounded by men who at first watch and are eventually drawn into the dance, Lewis distributes the sensuous, pulsing movements of the solo among three dancers. The solitary seductress is replaced by a collective ecstasy; the heterosexual pantomime dissolves into a boundless exuberance. This joy is shaded with a deep sadness: I saw minor matter twice, and cried during the bolero both times. I confessed this in my conversation with Lewis, and she told me, “Everyone cries at that part!”

Ligia Lewis’s minor matter. Image courtesy Hebbel am Ufer. Photo: Martha Glenn.

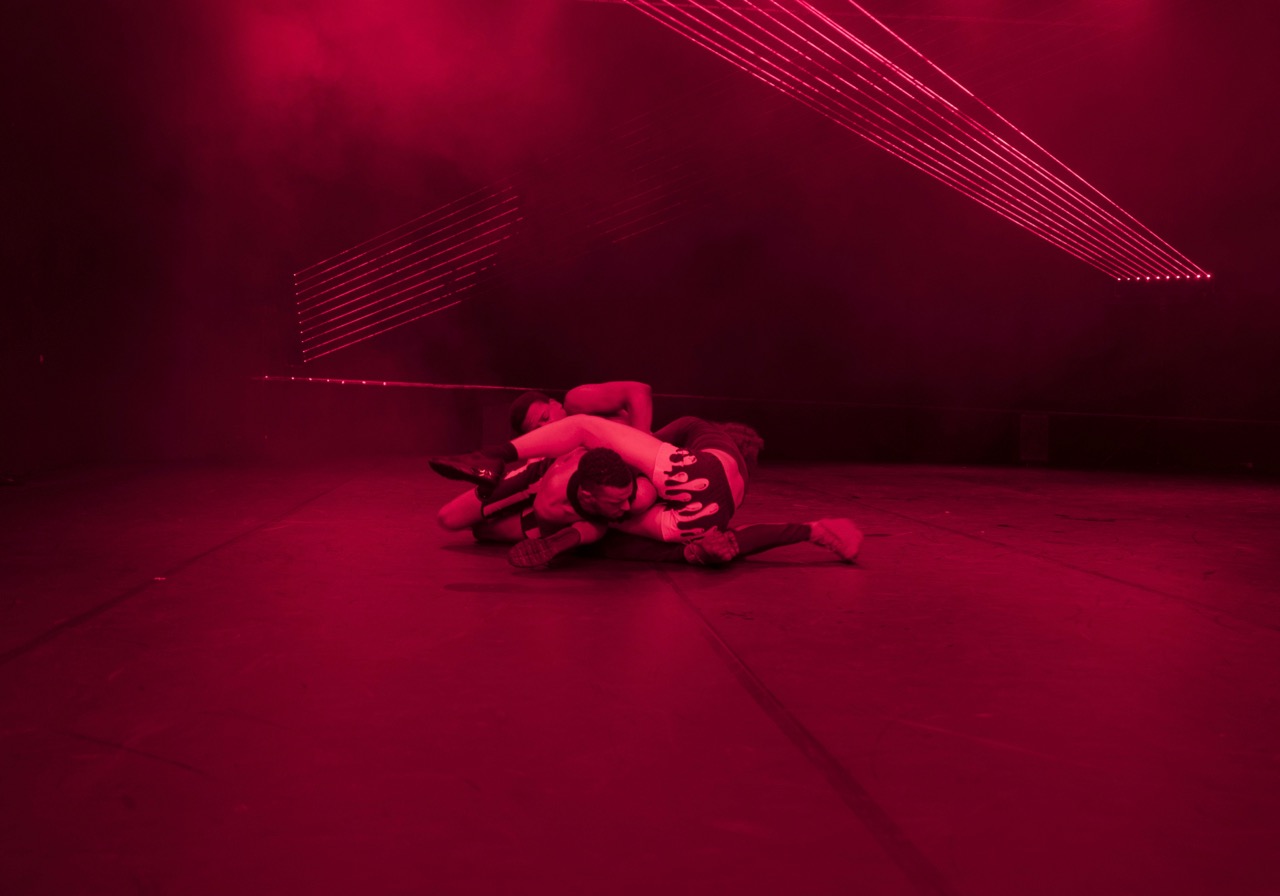

At times, Lewis tries to reduce the meaning of the dancing bodies to a minimum: a line. In the piece’s middle section, the dancers roll across the floor, their arms and legs extended; red lines of light, projected into the air by lasers, streak above them. They resemble shapes descending from an abstract and dimensionless sky in an arcade game, but the flesh remains. Pressing against the outer limits of black performance, minor matter recalls the theorist Hortense Spillers’s ideas about black embodiment. Spillers writes, “I would make a distinction . . . between ‘body’ and ‘flesh’ and impose that distinction as the central one between captive and liberated subject-positions. In that sense, before the ‘body’ there is the ‘flesh,’ that zero degree of social conceptualization.” Flesh is what bodies are made of, and blackness is what contemporary society is made of, in that it was the dispersal of African peoples across space and time that produced much of the enormous wealth that powered capitalism. Lewis articulates the flesh’s zero degree, but the inventiveness, humor, and energy of her choreography make her work far more than an illustration of theoretical principles, just as the real and particular existence of black people—or of anyone—overspills the concepts we use to think about ourselves in general.

Lewis herself has danced for a number of white choreographers over the course of her career. It’s tempting to read minor matter’s explicit encounter with blackness/performance as an exercise in self-authoring her own body, but this is complicated by the way Lewis dissolves herself into the trio of dancers who make up the piece—for example, in an intricate semi-improvised section where the three hold hands while moving in and through and with each other in a fused mass.

The choreography heads to the periphery of the theater and to the periphery of itself: about halfway through, Manekehla addresses an improvised speech to the wall of the theater, beginning, the first time I saw the piece, with a plea or challenge: “I want to be boring . . .” This offhand speech signals Lewis intentionally ceding control of her own work, but the desire to be boring also repeats a central theme in the work, of what it might mean to embody the history of blackness. Under this lens, there is no escape into being boring, no escape into abstraction.

Talking to the wall is a defining exercise in frustration, but Lewis and Gonzalez join Manekehla there, and then they all press up against it in a series of balances and holds. There’s a blur between their bodies that recalls, like so much of this work, the theorist and poet Fred Moten’s ideas about blackness as a radicalization of singularity. In his 2015 MoMA talk “Blackness and Nonperformance,” Moten describes blackness as “our more and less than singular being,” evoking a caress or gesture that forms a “social fabric bio-poetically brushing against a wall that opens up into a room.” Lewis’s work hits this same wall, the theater wall that demarcates and limits a space of performance, and opens it up into nonperformance. Toward the end of the piece, the trio grapple with and clamber on top of one other, calling out like children at play but with an adult exhaustion, and the house lights come up, revealing that a theater, too, is just a room, until—“Black! Black!”—the lights go out.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer based in New York and Berlin. Her solo show Soc or Barb is on view at Bodega gallery in Manhattan from January 14 to February 19, 2017.