Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

Resistance and survival: revisiting the Brazilian painter’s Capoeira.

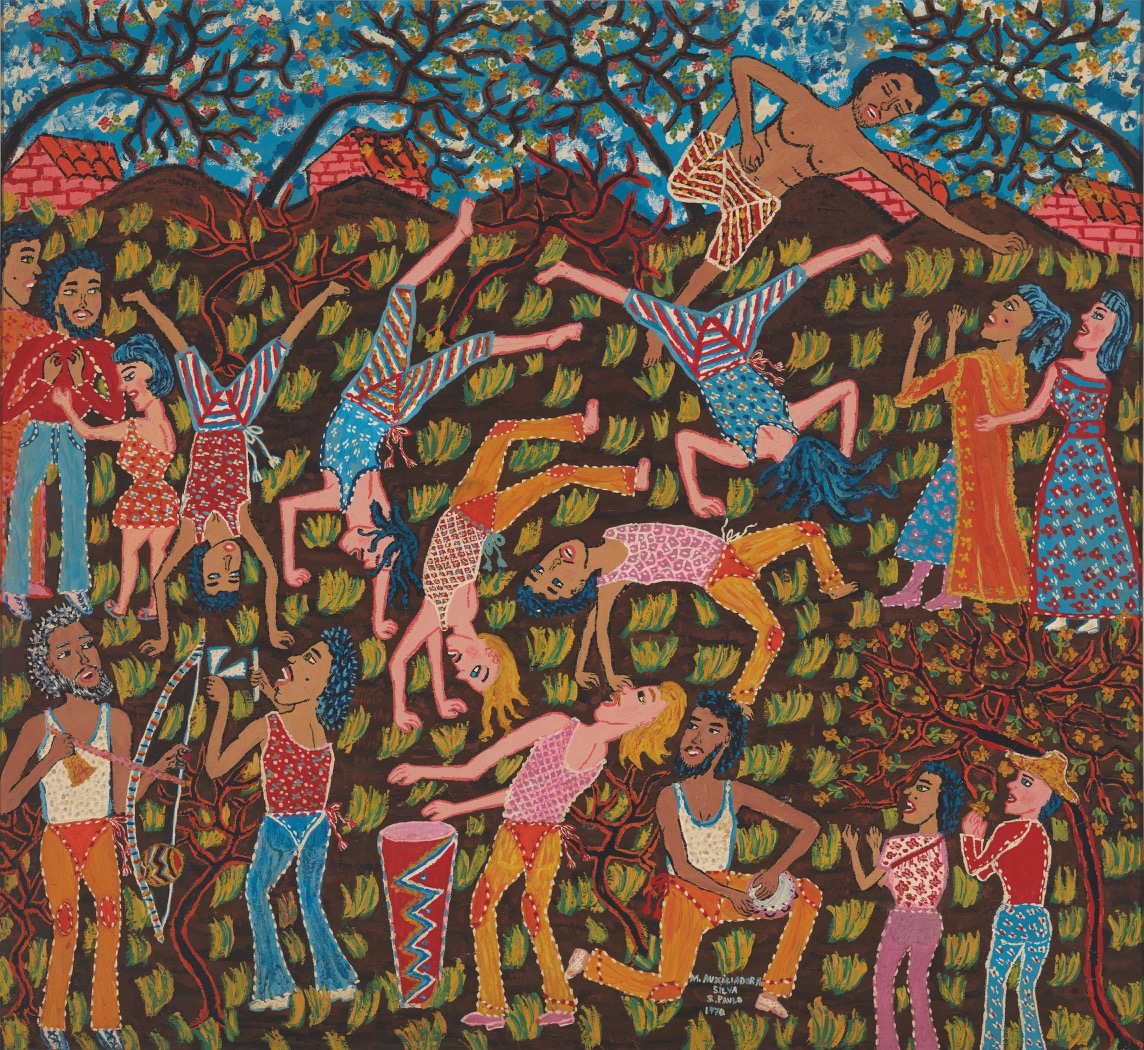

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, Capoeira, 1970. Oil and polyester resin on canvas, 69.5 × 75 centimeters. Photo: MASP.

Capoeira, by Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, available to view on the the Museu de Arte de São Paulo’s website

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that museum and gallery exhibitions remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to reflect on an artwork that is particularly significant to them and that is easily viewed online.

• • •

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva painted Capoeira in 1970, in the midst of the most intensely repressive years of the military dictatorship in Brazil. Not that you’d necessarily know that by looking at this canvas, which depicts a riotously joyful scene of music, sport, and movement. Auxiliadora’s mixed-gender and multiracial cast of characters are rhythmically arrayed across the picture’s surface, defying gravity as they twist and vault upside down, performing some of the titular martial art’s signature handsprings and cartwheels against a brown hillside speckled with tufts of grass and twisting tree branches. The figures do not crowd each other, but have been carefully allotted their own space—a lesson in how to negotiate physical proximities.

Like all of us with the extravagant privilege of living with electricity and ready internet connectivity, I’ve been spending a lot of time looking at my devices—at the faces of friends and students I would prefer to behold in the flesh, at the torrential flood of bad news, and, increasingly, at art posted on gallery websites. I have seen Auxiliadora’s painting in person; it is in the permanent collection of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), where I work as an adjunct curator. Examining a painting online is always a compromise—so much texture is lost—but I return to look at Capoeira on my computer because it seems to have a peculiar affinity with this kind of viewing; its bodies energetically occupy the foreground, pressed up against the picture plane whose flatness is akin to a screen.

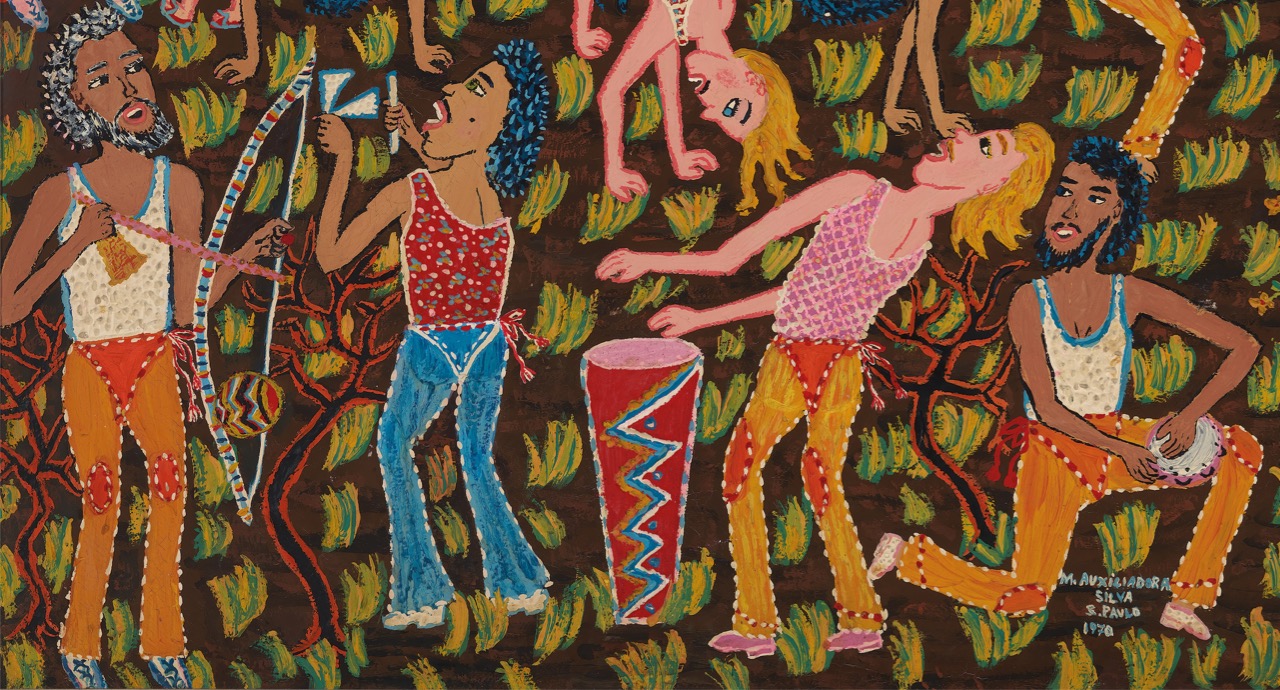

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, Capoeira (detail), 1970. Oil and polyester resin on canvas, 69.5 × 75 centimeters. Photo: MASP.

Adapted from an Angolan fighting technique, capoeira was invented by enslaved Afro-Brazilian people rebelling against captivity on Portuguese-run plantations in the colonial period. Its fierce nimbleness was viewed as so threatening to the social order that capoeira was outlawed, and punishments for practicing it included torture and death; it remained criminalized even after slavery was abolished in Brazil (it was the last country in the Western world to do so). Capoeiristas camouflaged their combat as dance, undertaking battles with the musical accompaniment of instruments, visible in Auxiliadora’s rendition, that include the atabaque (tall wooden hand drum), berimbau (single-string percussion bow), and agogô (metal bell).

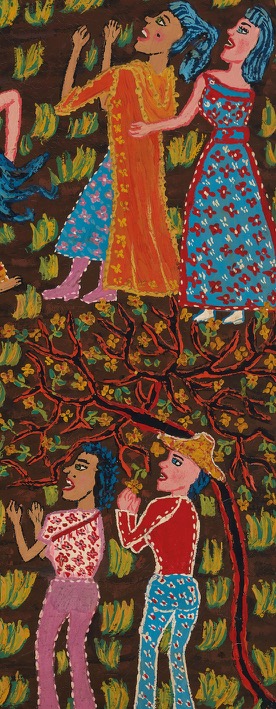

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, Capoeira (detail), 1970. Oil and polyester resin on canvas, 69.5 × 75 centimeters. Photo: MASP.

Auxiliadora was known for her depictions of Brazilian Black life, including tender scenes of intimacy between female friends. Though in the 1970s, and even today, she has been characterized as a “naive” artist, her works are technically skilled and conceptually complex. While she did not have formal academic training, she learned embroidery from her mother (who was also a sculptor), and her family was part of a larger artistic community steeped in cultural production of all kinds—music, wood carving, sculpture, painting, poetry, storytelling. She left school at the age of twelve to become a domestic housecleaner and later worked as a seamstress for factories in São Paulo. The detailed stitches on the garments worn by the figures in Capoeira and the composition’s embroidery-like embellishments demonstrate her deep knowledge of methods of textile construction. In many of her works, Auxiliadora built up surfaces, sculpting elements of relief from everyday materials that included her own black hair. And the hair of the capoeiristas in this piece is granted special attention—unruly blue and blond strands, splaying out like the winding branches of the trees, are so animated that they act as co-participants in the scene.

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, Capoeira (detail), 1970. Oil and polyester resin on canvas, 69.5 × 75 centimeters. Photo: MASP.

Just as its figures are arrested in their motions, so too is the painting currently in a state of suspension. It is installed at the indefinitely shuttered Museo Jumex in Mexico City; from there, it was supposed to travel as part of an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago that has been canceled. Now it is not known when it will return to MASP. In the midst of the current moment’s uncertainties, we turn to signs and portents, creating narratives to structure chaos. Everything has the potential to become an allegory. Even the artist’s name feels allegorical: in Brazil, Maria is a typical name for women across classes, and Auxiliadora, literally translated from the Portuguese, means helper. Hospitals throughout Latin America are called Maria Auxiliadora, after the devotional moniker: Mary, Our Lady, Helper of the Sick. But I do not come back to this painting because I am filled with longing or nostalgia for bodily liberties, outdoor space, or communal togetherness. Rather, I understand it as gesturing to two historical oppressions—slavery and dictatorship—as it portrays strategies of resistance and survival even in the direst circumstances.

In the 1970s, Auxiliadora had a lively career, participating in over thirty shows in Brazil and internationally, with her paintings consistently receiving positive press. Despite these successes, as an uncredentialed Black woman, she was marked as “lesser than,” and her art was not embraced as “high” in her own lifetime. Whose art is most valued? Whose lives are most valued?

As of this writing in mid-April, far-right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro has still refused to acknowledge the gravity of the coronavirus pandemic. Determined to pursue his strident anti-Black, anti-queer, anti-poor, anti-Indigenous agenda, he continues to shake the hands of his supporters and disastrously dismiss the virus as a “little cold.” One of the first deaths due to community spread in Brazil was a Rio housekeeper whose wealthy employer had returned from a holiday in Italy; it’s unclear if and when she told her maid she had fallen ill. It comes as no surprise that those who are already marginalized are bearing the brunt of this pandemic: cleaners, cashiers, nursing home workers, elderly folk, unhoused populations, inmates, people with disabilities, migrants, refugees. COVID-19 harshly highlights longstanding entanglements between health injustice, racial injustice, and economic injustice; disproportionate numbers of those who are dying are Black, brown, and Indigenous.

Maria Auxiliadora—blessed Mary, who helps us dream—died of cancer in São Paulo in 1974. She was only thirty-nine years old.

Julia Bryan-Wilson teaches at UC Berkeley and is Adjunct Curator at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, where her show Histories of Dance will be on view virtually and in catalog form this summer.