Erika Balsom

Erika Balsom

Porn, fantasy, and the city: rewatching Bette Gordon’s 1983 film.

Variety. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

Variety, directed by Bette Gordon, available to buy or rent on Amazon Prime Video; also available on DVD from Kino Lorber

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that most movie theaters around the country remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

In Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, his autobiographical 1999 account of sex and conviviality in New York City’s now mostly vanished porn cinemas, Samuel R. Delany recalls that in the mid-1970s, Variety Photoplays on Third Avenue “seemed almost a kind of family, with a neighborhood feel.” This sense of belonging was, he admits, predicated on an exclusion:

Its charm, sociality, and warmth—if it has any—depend entirely on the absence of “the woman”—or at least depend on flattening “the woman” till she is only an image on a screen, whether of light or memory, reduced to “pure” “sexuality,” till, a magical essence, a mystical energy, she pervades, grounds, even fuels the entire process, from which she is corporally, intellectually, emotionally, and politically absent.

Delany welcomes the idea that it could be otherwise. Female presence would do something he deems necessary, namely, “unmitigated violence to the West’s traditional concept of ‘women.’ ”

Sandy McLeod as Christine in Variety. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

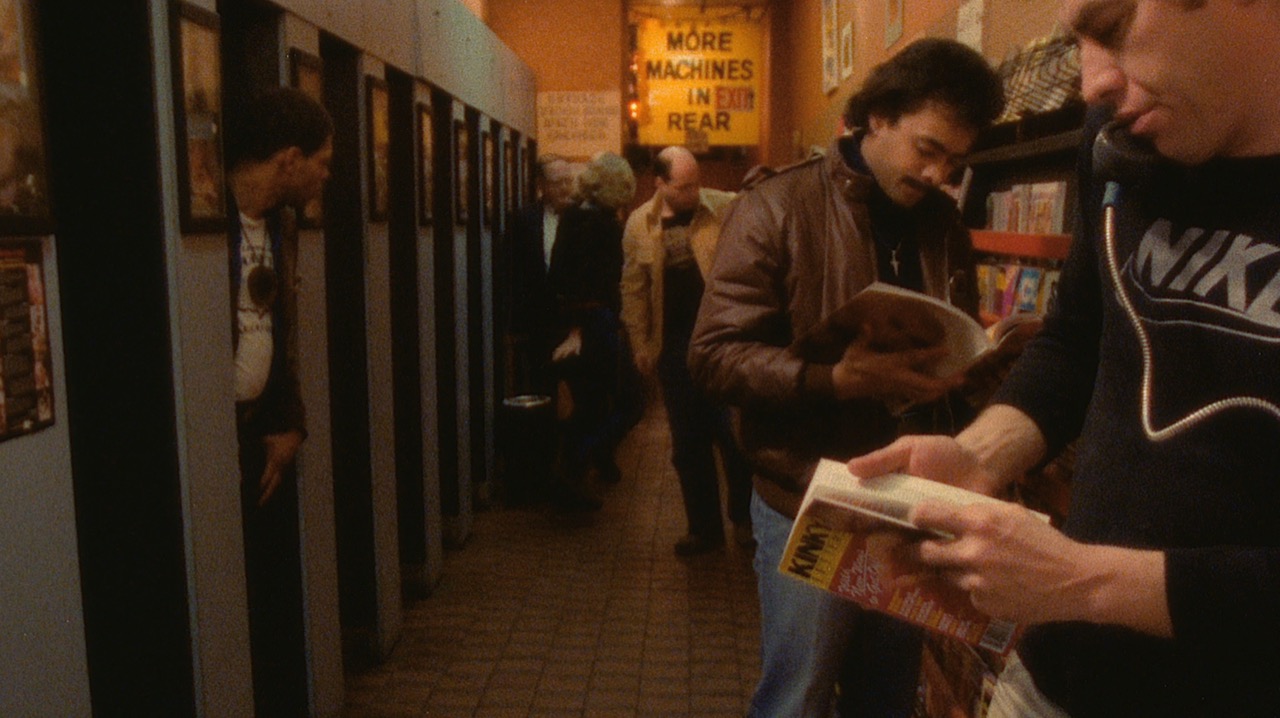

There are worse ways of describing what happens in Bette Gordon’s Variety (1983), a film that takes as its central location the same cinema Delany frequented. Gordon catapults the old nickelodeon and its gorgeous marquee into fiction, locating it in Times Square rather than the East Village and, more importantly, positioning a woman at its center. When Christine (Sandy McLeod), a nice Midwestern girl in need of a job, starts selling tickets there, she develops a fascination with the pornographic movies on view and begins to visit peep shows in the neighborhood. Her nascent voyeurism is not monopolized by sex films, though; a desire first sparked by the cinema spills out into her whole life. Her journalist boyfriend, Mark (Will Patton), now seems a prudish bore, while Louie (Richard M. Davidson), a Variety customer likely involved with organized crime, intrigues her. After her first date with Louie is cut short, she begins to follow him, moving through the city, claiming the right to be the protagonist of her own story. In an inversion of the gender roles typical of film noir, she is the one who investigates, he the enigmatic object of investigation. Christine propels a loose narrative in which pornography kickstarts an exploration of the limits of fantasy and the possibilities of female agency in the world of men.

Variety. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

Variety was Gordon’s debut feature, made after a series of accomplished experimental shorts roughly aligned with the tendency philosopher of art Noël Carroll dubbed the “new talkies”—films made mainly by women that broke with the formalism that had dominated the avant-garde to embrace narrative, semiotics, and subjectivity. Gordon’s Super 8 work Anybody’s Woman (1981), named after the wonderful Dorothy Arzner film of 1930 and available to watch on Vimeo, was commissioned for seventy-five dollars as part of an exhibition at Artists Space. In just over twenty minutes, it offers a sketch for Variety. Almost all the component parts are there: the eroticism of the city, a woman’s curious gaze, sexually explicit monologues, and the provocation that the governing logic of 1970s porn isn’t so different from that of classical Hollywood.

What isn’t there in Anybody’s Woman is a story to hold it all together. When this arrives in Variety, courtesy of a screenplay by Kathy Acker, it is just traditional enough that it might not seem too off base to see the film as an attempt to break into the mainstream. Through this lens, the movie comes up lacking. A 1985 New York Times review is indicative: for Janet Maslin, Variety suffers from “a painfully underwritten screenplay . . . and a static, uncommunicative directorial style.” The film is better considered within the tradition of the avant-garde it emerged from, one inspired by Brechtian techniques, for which static performances and elliptical plotting held special interest as a means of puncturing the illusory plenitude of Hollywood. Studio conventions are not aspirations for Variety; they are things to tamper with and dismantle.

Richard M. Davidson as Louie (left) in Variety. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

Woven throughout the film are hints of another story unfolding in the background, a story of money and corruption in which Louie and Mark would be the leads. Christine’s glimpses of this world take on an almost hallucinatory quality, akin to the sexual fantasies she sees onscreen. The mystery of men shaking hands and sealing deals would usually be the center of the action, but here it recedes to the margins, leaving ample space for views of the city and scenes in which women—played by downtown luminaries Nan Goldin and Cookie Mueller, among others—together discuss their experiences of sex and work. This naturalism collides with flights into high artifice, most notably in a series of increasingly pornographic monologues Christine recounts to a nonplussed Mark, freezing the narrative with the anti-spectacle of sex acts turned into speech acts. The eruption of this alien discourse compromises any realist impulse the film might possess, pointing to just how inassimilable frank expressions of female desire are to dominant representational codes.

Sandy McLeod as Christine and Nan Goldin as Nan in Variety. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

Brecht was de rigueur for feminist film theory in Variety’s time, but pornography wasn’t. Gordon’s affirmative, or at least nonjudgmental, depiction of Christine’s trajectory clashes with contemporaneous polemics against visual pleasure, to say nothing of how it pushes back against feminists like Robin Morgan, who marched on Times Square in 1979 as part of the Women Against Pornography group and claimed, “Pornography is the theory, and rape is the practice.” (An anti-porn feminist would probably see Variety as a dangerous parable of internalized misogyny.) With its emphasis on voyeurism and objectification, the film doesn’t conform fully with what some critics today characterize as the “female gaze,” either. But all this friction speaks to the movie’s enduring interest. No simple tale of empowerment, Variety fiercely refuses to be held up as an unproblematically good object and is all the better for it. Its final sequence, an inventive repurposing of the empty streets that famously close Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse (1962), drives home the idea that what is powerful and potentially emancipatory about fantasy is precisely that it is fantasy, unfurling in relation to reality but separate from it, full of complexity and contradiction. It is an imaginative space where we are free to want what we might not actually want. Through its conflicted account of a woman’s relationship to projections of her desire, Variety suggests we think of cinema the same way.

Erika Balsom is the author, most recently, of An Oceanic Feeling: Cinema and the Sea, published in 2018. She is a senior lecturer in Film Studies at King’s College London and writes criticism for publications including Artforum, frieze, and Sight & Sound. In 2019, together with artist Éric Baudelaire, she was awarded an UNDO Fellowship from Union Docs.