Leslie Camhi

Leslie Camhi

Memory Lost, the photographer’s first New York solo show in five years.

Nan Goldin, Memory Lost, 2019–21 (installation view). Digital slideshow; 24 minutes, 16 seconds. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Nan Goldin.

Nan Goldin: Memory Lost, Marian Goodman Gallery, 24 West Fifty-Seventh Street, New York City, through June 12, 2021

• • •

Nan Goldin is my near contemporary, and we’ve often lived in the same city, and even the same neighborhood—the East Village, for example, when The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Goldin’s groundbreaking, shockingly intimate slideshow chronicling late 1970s and early 1980s bohemia, was making the rounds of the clubs at night. But our milieux overlapped only slightly, and we crossed paths just once. At the time I was involved in a doomed, long-distance love affair with an artist. I believe he and Goldin were then working with the same Paris gallery, and so perhaps that’s how, one night after an art opening, we all ended up seated together at a bar downtown in 1990s New York. Somebody that evening casually suggested that Goldin might want to photograph me, so she took, as the saying goes, a good look at me, placing her hand on my chin and gently turning my head to study it in profile.

The photograph, alas, never happened, but I will always remember the curious professionalism of that gesture, and the quality of Goldin’s gaze in that moment, a split-second visual appraisal, at once as sharp as a surgeon’s scalpel and tender as a caress.

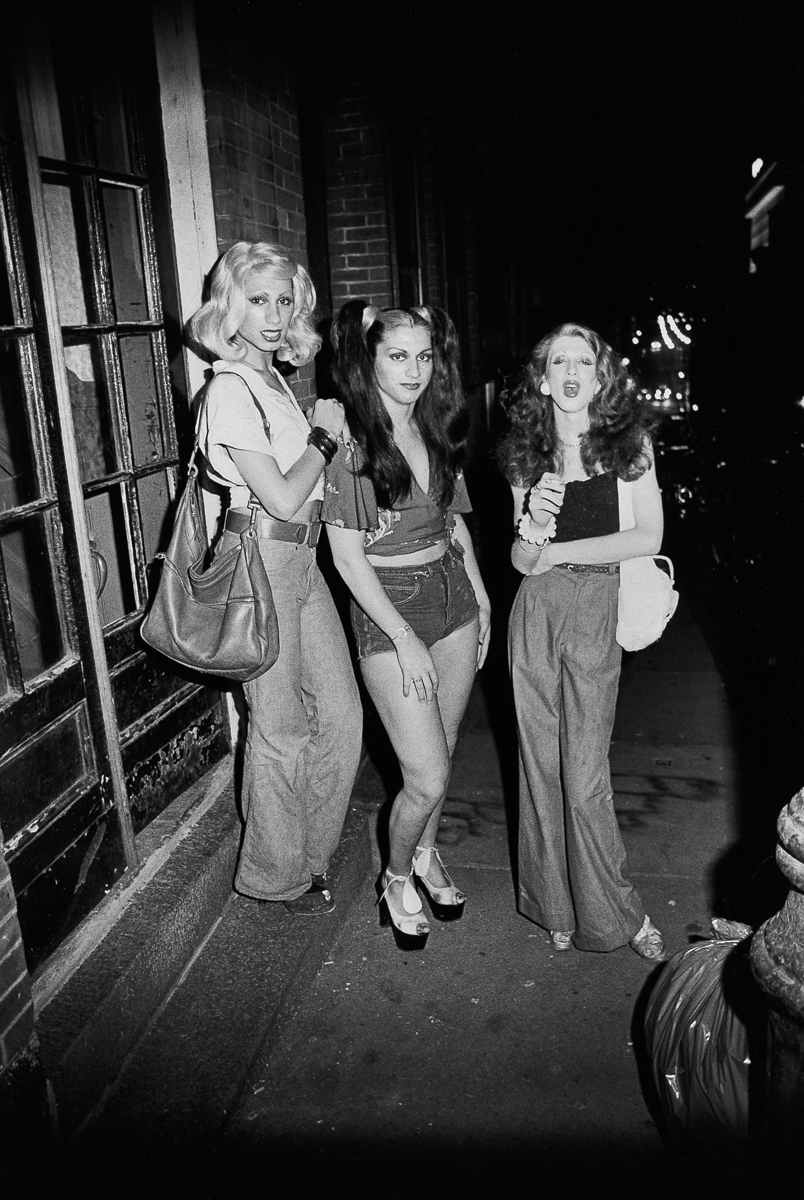

Nan Goldin, Best friends going out, Boston, 1973. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 16 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Nan Goldin.

Did we know then that we were living through history? Goldin seems to have always known it. Her superpower, sui generis in its visual efficacy, is to seemingly abandon herself to life—to the love of friends, with their beauty and enduring strangeness, to passion and its brutal aftermath, to the rootless nomadism of a contemporary art star, or the bonding, euphoria, blackouts, and soul-shattering trials of addiction—while standing just far enough outside herself, perched on the thin ledge of the will to remember, in order to take the picture.

Nan Goldin, The Other Side, 1993–2021 (installation view). Slideshow; 16 minutes, 46 seconds. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Nan Goldin.

She is a survivor many times over: of family trauma, most wrenchingly her adored elder sister’s suicide at eighteen; of intimate partner alienation and abuse (Ballad’s raw and desolating fulcrum); of AIDS, a bullet she dodged, but which contributed to the deaths of so many of the people in her pictures; and of addiction, which took the lives of many others, and has engulfed her own repeatedly.

Nan Goldin: Memory Lost, installation view. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Nan Goldin.

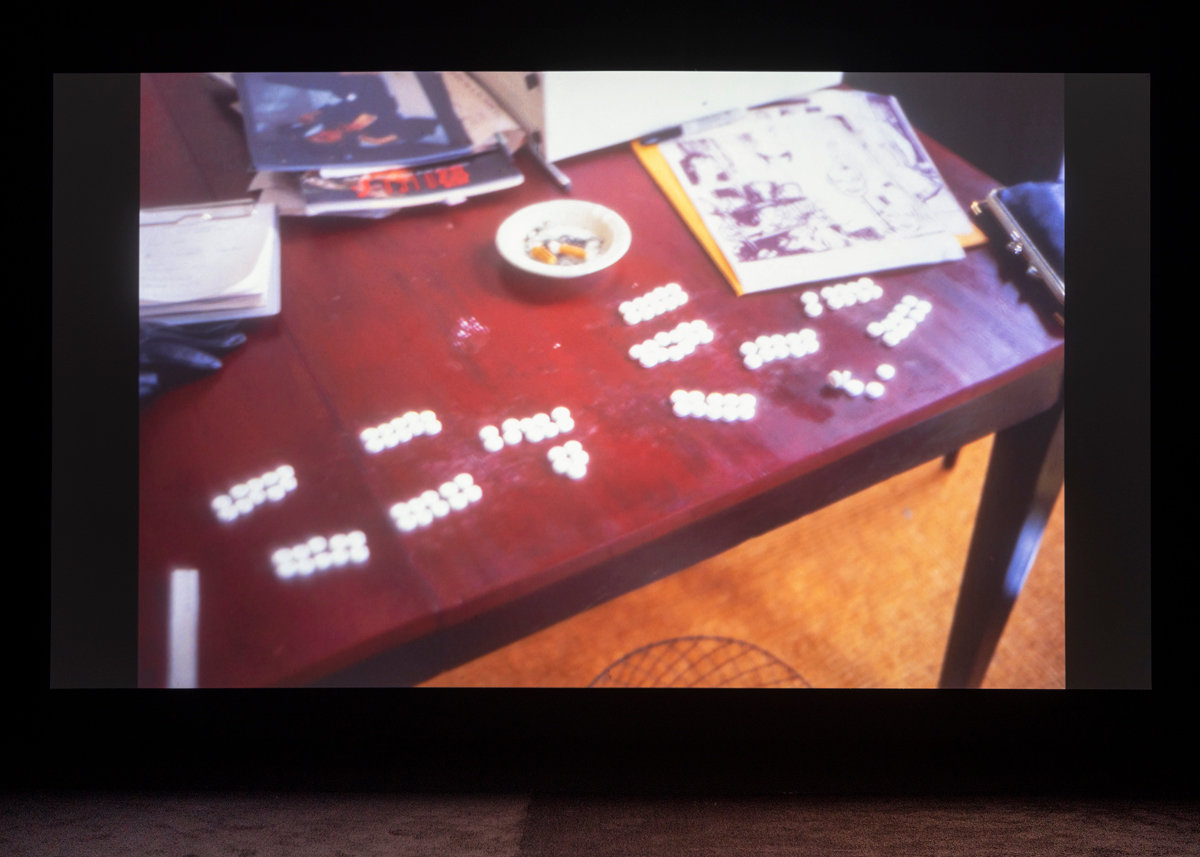

Memory Lost—a five-part solo show, Goldin’s first in New York in five years, currently on view at Marian Goodman—includes some of her earliest work, black-and-white photographs taken at the Other Side, the drag-queen club in Boston where she and her friends went almost every night in the early ’70s. But the exhibition’s title is drawn from that of a new digital slideshow, made between 2019 and 2021, and whose focus is addiction. Goldin has said that she began photographing while doing drugs later in the ’70s so that she’d have a record, when her memory failed her, of what had happened the night before.

A palimpsest drawn from decades of slides, clips of home movies, and messages left on Goldin’s answering machine during a two-year drug binge in the mid-’80s, as well as recent interviews with people in recovery and medical specialists, this bracingly honest work evokes both the lure and thrill of playing with addiction’s fire, and the desperate chill that descends when the walls of dependence begin closing in.

Sweet and wistful footage of young friends innocently frolicking in the kitchen or on the beach in the 1970s act as bookends to a sinister visual odyssey that includes stills of passed-out partygoers and seedy rooms in disarray, a burnt mattress, buildings that seem to shake, and menacing blood-red or moonlit skies. On the soundtrack, interspersed with Mica Levi’s haunting score, are phone messages: from a dealer, letting Goldin know that he’s got the goods (“How many did you get?” “All that you wanted”); from a friend at the end of his rope, telling her he’s heading to rehab; and from another friend (later ID’d as curator Marvin Heiferman), a voice of sanity, begging Goldin to “WAKE UP! WAKE UP! WAKE UP!”

Nan Goldin, Memory Lost, 2019–21 (installation view). Digital slideshow; 24 minutes, 16 seconds. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Nan Goldin.

Addiction bends time—in the relentless alternation between getting high and coming down, Goldin’s parade of imagery suggests, whole years go by. We hear the voice of a former user who recounts looking out his apartment window, seeing the corner grocer putting out apples, and thinking, Oh, it must be the fall. We see monkey figures on the clock-tower bell in the Central Park children’s zoo, beating out the hour as the soundtrack builds with frantic intensity—time to cop.

Nan Goldin, The sky on the twilight of Philippine’s suicide, Winterthur, Switzerland, 1997. Archival pigment print mounted on 2mm dibond with chassis, 59 × 88 5/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Nan Goldin.

Soon the bodies begin piling up. Friends die due to AIDS-related complications or overdoses, their framed pictures, in impromptu altars, draped with flowers. Goldin finds herself wandering through Dante’s “dark wood” (in which, halfway through the journey of his life, the poet loses himself) before arriving at the Priory, a rehabilitation clinic in London—a white castle out of a demented fairy tale. There, she photographs the covered dinner tray resting on the desk in her room—prosaic sustenance. How can it compare with the artificial paradises that drugs have given her?

Activism against Big Pharma and the billionaire makers of Oxycontin, the drug at the center of this country’s opioid crisis, has preoccupied Goldin in recent years. Memory Lost tells a more personal story. “It’s Mom’s arms,” another survivor, interviewed by Goldin, says about dope. “Yeah. Mom’s arms . . . You never feel safer, you never feel more secure.” The work is at once a memorial for the years and the people she lost to drugs, and a plea for understanding.

Nan Goldin, Sirens, 2019–21 (installation view). Single-channel video; 16 minutes, 1 second. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Nan Goldin.

A companion video, Sirens (2019–21), is playing one room over. Entirely compiled from passages taken from Goldin’s favorite films, spliced together, and set to another eerie score by Levi, it’s a sixteen-minute deep dive into the abstract, sensual allure of hallucinogens and narcotics, starring various female figures. The only two scenes I could identify with certainty involved Romy Schneider ecstatically pouring a glass of water in Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno (1964) and Donyale Luna modeling in William Klein’s 1966 satire of fashion excess Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? The video is dedicated to Luna, born Peggy Ann Freeman in Detroit—a woman of otherworldly beauty whose meteoric rise in the fashion world of the ’60s and ’70s, where she was the first African American to grace the cover of Vogue, ended with her 1979 death in Rome from a heroin overdose.

Sirens is both hypnotic and suffocating, and it was something of a relief to step into a room containing Goldin’s new series of still photographs, portraits of the writer Thora Siemsen taken in the Clinton Hill apartment she shared with Goldin during quarantine. The two had met when Siemsen interviewed Goldin just before Christmas in 2019; they kept talking through January, and when the lockdown began in March, they decided that Siemsen would move in with her. For the restless nomad who spent decades running—from addiction, from celebrity, from herself—the confinement and challenges of quarantine must have been particularly fraught. It is comforting to see that, with Siemsen’s help, Goldin has maintained her sanity, sobriety, and artistic vision, producing painterly photographs of her roommate, infused with the stillness and composure of a Dutch master.

Nan Goldin: Memory Lost, installation view. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Nan Goldin.

Looking at these images, which are both intimate and discreet, I realize that one of the main projects that has occupied Goldin these many years, in her long, sometimes frenzied flight from bourgeois convention, is a reordering of the hierarchy of human relationships, with friendship—defined with the greatest elasticity—at its center. Who belongs to whom? How do we define family? And is the camera an instrument of capture and possession, or a means of sharing experience on the fly?

For love fades, friendships unravel, people die. But something of their soul remains preserved in photographic emulsion or as flickering projections in a darkened room.

For over two decades, New York–based author and cultural critic Leslie Camhi’s essays on art, architecture, books, fashion, film, and women’s lives, including her own life and travels, have appeared in major US publications, such as the New York Times and Vogue. The author of numerous catalog essays on artists (and one legendary art dealer, Ileana Sonnabend), she also holds a doctorate in comparative literature from Yale University, and her scholarly publications include essays on female kleptomania and nineteenth-century French medical photography. Her translation from the French of Violaine Huisman’s award-winning novel, The Book of Mother, will be published by Scribner on October 5, 2021.