Jean-Christophe Castelli

Jean-Christophe Castelli

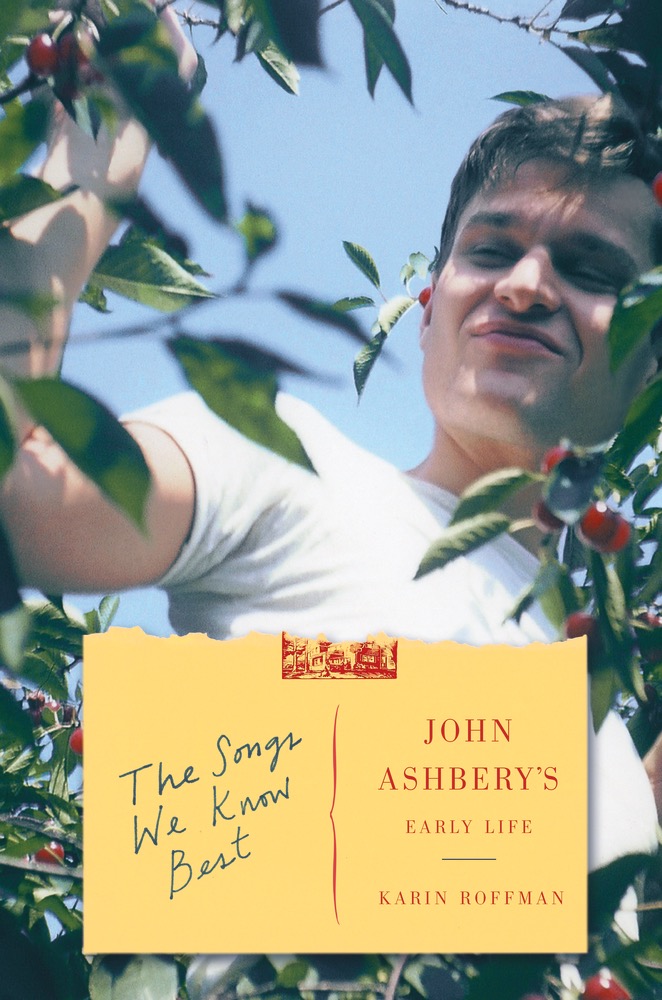

From the apple orchard to Quiz Kids to the New York School: a biography of the young John Ashbery.

The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life, by Karin Roffman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 316 pages, $30

• • •

1.

With so many of my Facebook friends obsessively serving up the latest steaming pile of outrage from Washington, I recently tried a different tack and posted one of my favorite poems by John Ashbery. The poem was “But What Is the Reader to Make of This?” (from 1984’s A Wave), and the answer was, clearly, not much: my posting got exactly two “likes.” But I’d prefer to think that’s more my bad—low social-media profile—than Ashbery’s.

For me in any case, the poem kind of resonated with our current climate of uncertainty, with its image of watching “the centuries begin to collapse / Through each other, like floors in a burning building . . .” History is fraught and a “battle rages,” Ashbery tells us, but in the end,

. . . The surprises history has

For us are nothing compared to the shock we get

From each other, though time still wears

The colors of meanness and melancholy, and the general life

Is still many sizes too big, yet

Has style, woven of things that never happened

With those that did, so that a mood survives

Where life and death never could. Make it sweet again!

“But What Is the Reader to Make of This?” Good question. Though this is one of his more accessible poems, Ashbery’s thoughts race as always through the perilous landscape with Road Runner speed—stop too long to look for meaning and you might find yourself suspended over the void like Wile E. Coyote, clutching a useless bag of Acme interpretive strategies. (As good an image as any for the act of reading a poet whose works include “Daffy Duck in Hollywood” and a classically strict sestina on Popeye.)

More than anything, it’s a mood that survives the reading of an Ashbery poem—a very American feeling of openness and possibility. Like Whitman, whose long lines he sometimes emulates, Ashbery contains multitudes. Maybe that’s why his work speaks to me right now in a way that more politically engaged poetry does not: it’s good to take a stand, but we also need space for freedom and multiplicity amid all the meanness and melancholy of our partis pris. And “Make it sweet again!” is not a bad counter-slogan for our times.

2.

I was pleasantly surprised to see “my” poem gracing the dust jacket of The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life, Karin Roffman’s concise and excellent new biography. Ashbery, who turns ninety next month, is a reluctant subject, but Roffman managed to gain access to childhood journals, writings, letters, photographs, and the poet’s own memories. Starting with Ashbery’s birth in 1927, her book describes a series of widening circles, from the small upstate New York farm community of Sodus through Deerfield Academy, Harvard, and the coterie of poets and friends that came to be known as the New York School. We leave Ashbery in 1955, just as he’s finally breaking out, having made a strong publishing debut with Some Trees (chosen for the prestigious Yale Younger Poets series by W.H. Auden, who doesn’t quite seem to have gotten it), and embarking for Paris on a Fulbright.

Roffman, a sensitive reader of Ashbery’s poetry, explores the roots of Some Trees and much of his subsequent work. Ashbery’s personal life doesn’t pop out of his lines like it does with Frank O’Hara’s, who versified every lunch date and party (including the one thrown by Ashbery in 1949 that serves as The Songs We Know Best’s festive prologue). But Ashbery’s childhood enthusiasms—the cultural bits and pieces that he collaged into a sense of self—are very much present in his poetry, as is the sparse western New York landscape where he grew up. The restless boy trapped amidst the trees in “Orioles,” for example:

And that night you gaze moodily

At the moonlit apple-blossoms, for of course

Horror and repulsion do exist! They do! And you wonder,

How long will the perfumed dung, the sunlit clouds cover my heart?

The apple blossoms are those of his father’s orchard, and if Ashbery has a bad madeleine, a remembrance of things best forgotten, it might be the taste of Golden Delicious and McIntoshes, whose harvesting and crating were among the least favorite chores of his childhood, which was generally one of frustration, isolation, and boredom on the farm.

Classical music, movies, radio serials, encyclopedias, and the imaginative play of writing became Ashbery’s refuge during this mostly uneventful period of growing up. “Nothing worth the ink, so good night,” as Ashbery would write in his diary—except for the tragedy of his younger brother Richard’s death from leukemia, and a brief and exhilarating opening onto the larger world when the nerdy teen was selected to compete in Quiz Kids, a wildly popular radio show in Chicago. The episode was broadcast just a few days after Pearl Harbor, and indeed, the “burning building” of history casts its sullen, angry glow over the rest of Ashbery’s childhood and young adulthood: World War II, Korea, the Cold War, and the red- and gay-baiting of McCarthyism.

Ashbery’s coming into his own sexuality seems typical of the time—feelings of confusion and being “different” lightened by poignant glimpses of possible happiness through furtively brief relationships with other boys. A tall, self-possessed sixteen-year-old “whose angular face resembled Frank Sinatra’s,” Ashbery left Sodus for boarding school, which provided more opportunities to meet kindred souls, but also greater risks of exposure. Harvard was not always welcoming either, as even the Advocate, the celebrated campus poetry magazine, was traditionally homophobic in its attitudes.

The Songs We Know Best hits a high note when Ashbery moves to New York City in 1949 and finally finds his seat at the moveable feast of art, poetry, love, and friendship. At this point, O’Hara’s wildly expansive and bitchy personality steals some of the limelight, along with a few friends and lovers, from Ashbery. (In the New York School, O’Hara is Mr. Popularity to Ashbery’s Quiz Kid, with Kenneth Koch as Class Clown.) For more dish, you might turn afterward to City Poet, Brad Gooch’s lively biography of O’Hara. But meanwhile, stick with Roffman as she puts the finishing touches on her portrait of the poet. Having gotten acquainted with Ashbery’s appealing, low-key personality, you’ll return to his work, as you should, with a deepened appreciation for the unique voice—dry, witty, bemused, and melancholy—that gives Ashbery’s poetry a compelling unity even in the midst of its sometimes bewildering multiplicity. Like few other artists (Robert Rauschenberg comes to mind in the wake of his current MoMA retrospective), John Ashbery is a deeply humane and generous—a necessary—figure who makes it sweet again, and again.

Jean-Christophe Castelli is a New York City-based producer and screenwriter, most recently on Ang Lee’s 2016 feature, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. He is also the author of The Making of Life of Pi (Harper Design, 2012), and his writing has appeared in Vanity Fair, Esquire, Elle, The Village Voice, and other publications.