Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

Paris Barclay’s new documentary presents a moving portrait of a lonely, beloved, enigmatic musician.

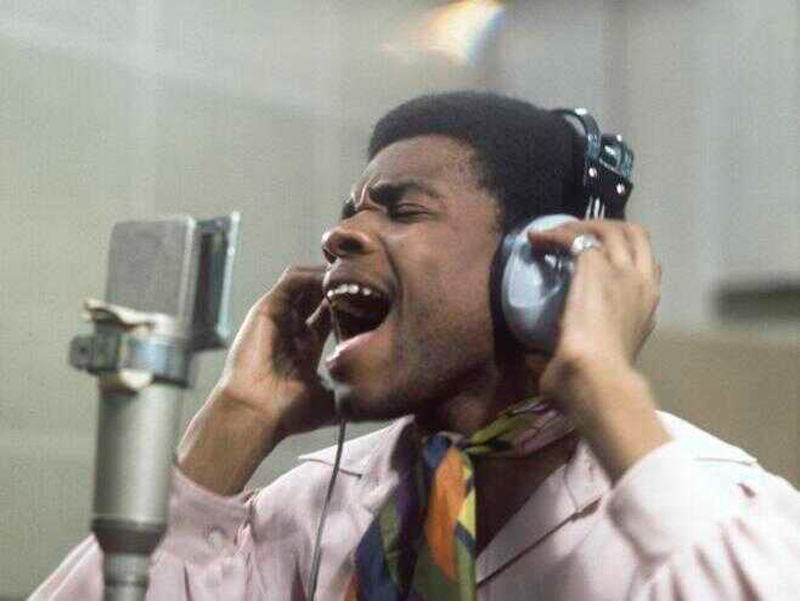

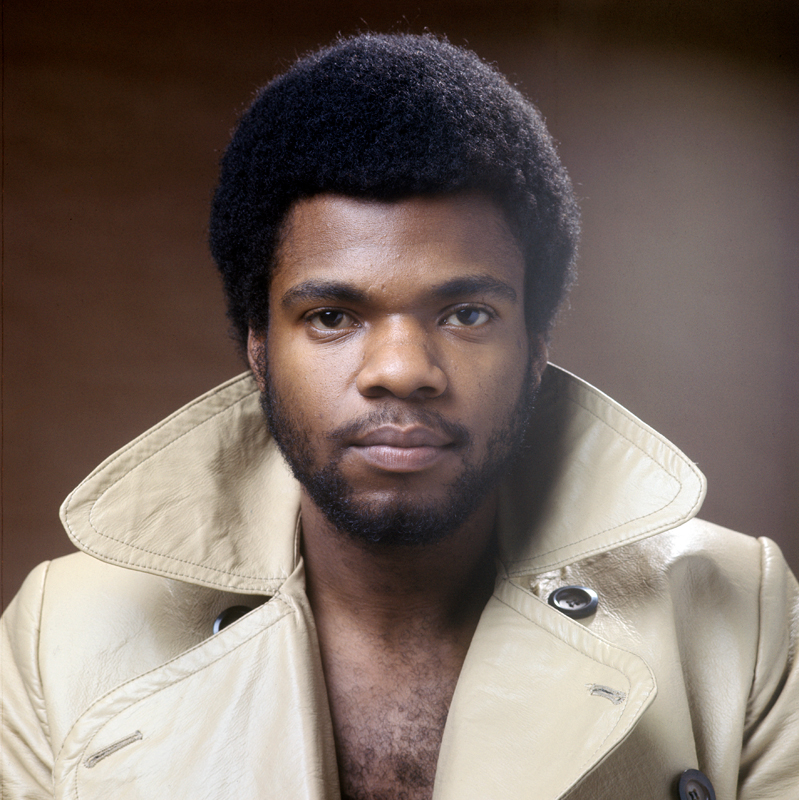

Billy Preston in Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It. © Abramorama.

Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It, directed by Paris Barclay, now playing at Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City

• • •

Like Mick Jagger’s pout and Nina Simone’s scowl, Billy Preston’s joyous gap-toothed grin is one of the most compelling facial expressions in modern show business. It turns up with relentless frequency in Paris Barclay’s Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It, a documentary that—like so many about hard-living musicians—attempts to reconcile its subject’s ecstatic artistry with his private struggles. Even as the film’s rundown of biographical details gets increasingly grim, that smile clings to Preston through every stage of his life, from his early experiences as a boy genius winning the approval of his idols to his short-lived era of fame as a solo artist and his tumultuous final years. Eventually, this beaming visual anchor reveals a dual purpose: as much as it was a measure of the man’s genuine exuberance, it was also a powerful deterrent that kept loved ones from asking questions about his childhood traumas and semi-closeted gay identity.

In the twenty years since his death, at the age of fifty-nine, Preston has held a less than stable place in our cultural memory, perhaps owing to his relatively small repertoire of signature hits, his lack of a career-defining album, and his resistance to being pigeonholed into any single genre. That’s the Way God Planned It does an admirable service in bringing his talents back into the spotlight, drawing on a wealth of footage from across his five decades as a performer. In these archival finds, we see Preston not just as a gifted singer, instrumentalist, and composer, but also as an indelible persona. At a startlingly young age, he held his own alongside the likes of Nat King Cole and Mahalia Jackson. Then, in his prolific, sometimes gloriously bewigged prime, he stole the show from more famous peers like the Beatles (of whom he is often considered a fifth member, thanks to his contributions to Abbey Road and Let It Be), the Rolling Stones, and Eric Clapton. Whether planted behind a keyboard or hamming it up with his irrepressibly kinetic stage presence, Preston had an instinct for delighting an audience.

Billy Preston in Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It. © Abramorama.

Barclay’s conventional, VH1-style approach mostly forgoes broader cultural analysis (and steers clear of the sweeping theory of Black genius that undergirds Questlove’s recent Sly Stone documentary, Sly Lives!), but the film does clarify Preston’s remarkable role in bridging musical idioms—the sacred and the secular, American R & B and the British Invasion. It’s rare to see a musician move as fluidly and unselfconsciously as Preston did across the entertainment industry’s racialized categories—especially in as segregated a time as the 1960s and ’70s—and so nimbly highlight the Black origins of rock and roll. For all his cultural dexterity, Preston sustained a lifelong commitment to the sounds of the African American church, exemplified by his sublime command of the Hammond B3 organ. Preston’s gospel roots are on display in many of the film’s most captivating segments, including one that shows him improvising his gorgeous Fender Rhodes accompaniment on the Beatles’ “Don’t Let Me Down,” leaving the group visibly dazzled; and another featuring a barn-burning performance of George Harrison’s “Isn’t It a Pity,” delivered at a 2002 tribute concert honoring the deceased legend, to whom he was particularly close.

Through its focus on Preston’s collaborations with other artists, That’s the Way God Planned It mounts an argument for the importance of non-headlining personnel in rock history. It’s clear that Preston—similar to other revered sidemen like Bernard Purdie and Clarence Clemons—would have been pantheon-worthy even if he’d never struck out on his own. At the same time, it’s hard not to conclude that Preston’s professional connections hindered his own creative evolution and prevented him from becoming an icon of equal magnitude. Two of his best-known singles—“That’s the Way God Planned It” and “Will It Go Round in Circles”—are introduced in the film as outgrowths of Beatles songs. Perhaps the most famous composition he ever wrote, “You Are So Beautiful,” has always been more widely associated with Joe Cocker, whose rendition became a global hit. And, as the movie implies, Preston’s style may have been a victim of its own transmissibility, becoming an uncredited inspiration for such beloved funk acts as Sly and the Family Stone, Rufus, and the Brothers Johnson.

Still, Preston’s virtuosity shines through. Bolstering his star power are the testimonials of a convivial cast of talking heads, who speak about him with a mix of love and bewilderment. Some describe him as an enigma; veteran R & B biographer David Ritz notes that his repeated attempts to get Preston’s life story down on paper were thwarted by the singer’s unwillingness to discuss anything other than music. Some cautiously speculate on Preston’s experiences of sexual abuse as a child entertainer on the road, euphemistically referring to him having been “touched” or “taken advantage of.” Others, like soul great Sam Moore and Preston’s writing partner Bruce Fisher, extol his brotherly sense of loyalty. Most haunting of all is the notoriously ill-tempered Clapton, who shows a tender side while reminiscing about his friend, occasionally tearing up, and while recounting his efforts to help Preston through a period of addiction, incarceration, and health problems.

As a portrait of a queer Black musician who came of age in the early years of gay liberation but didn’t enjoy its benefits, Barclay’s film shares a thematic kinship with the 2024 Luther Vandross documentary Luther: Never Too Much. But unlike the tremulously lovesick Vandross, Preston was not an artist who embraced romantic longing as vital material; his music is less intimate, less suggestive of hidden depths. And while Luther broaches the topic of sexuality in hushed tones, reflecting its subject’s fiercely guarded privacy, That’s the Way God Planned It makes evident that Preston knew his relationships with men were an open secret, and that he operated under a don’t-ask-don’t-tell policy that his friends and colleagues never challenged. Despite these differences, both films leave us with a similar feeling of loneliness—a sense that, no matter how adored these men were, their innermost truths eluded the comprehension of those closest to them. In That’s the Way God Planned It, the effusive praise heaped on Preston is touching but also sad and unnerving, a reminder that to be loved is not necessarily to be known.

Andrew Chan is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of Why Mariah Carey Matters, published by University of Texas Press.