The Clock

Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

A racing pulse beneath the skin: Vincente Minnelli’s 1945 melodrama.

The Clock, directed by Vincente Minnelli, available to buy or rent on Amazon Prime Video, Google Play, iTunes, Vudu, and YouTube

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that most movie theaters around the country remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

There’s nothing invariably interesting about watching people fall in love, as anyone who has witnessed it in real life can attest. Romance (at least the monogamous variety) demands the maintenance of a world apart, a gated paradise that only ever has room for two. Given how much this kind of love thrives on insularity, how is it that the most persuasive screen romances reach out and embrace the audience, drawing us into a privileged intimacy with their characters? Sometimes the more formulaic the plot, the more mysterious the effect. It’s as if the parameters of the old boy-meets-girl storyline allow us to recognize that our own passions—as ineffable and unprecedented as they often seem in the moment—are the product of the same rather predictable laws that have always governed human behavior.

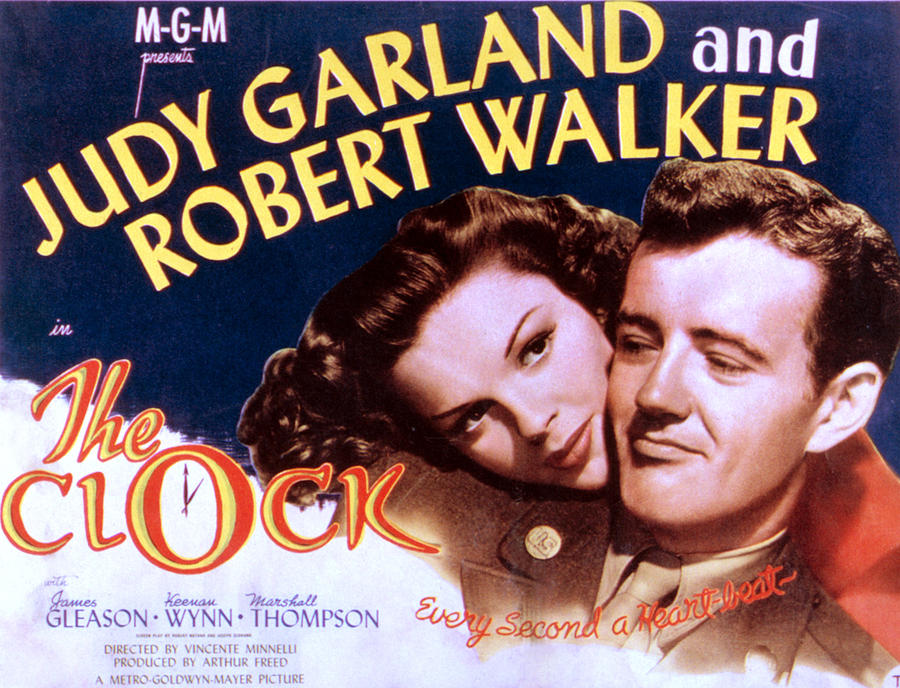

Vincente Minnelli’s 1945 melodrama The Clock slots comfortably into this tradition, presenting its central couple as a pair of all-American anybodies. He (Robert Walker) is a wholesome GI named Joe, deposited into Penn Station with forty-eight hours to kill before heading overseas. She (Judy Garland) is a reasonably skeptical urban professional named Alice who trips over his outstretched legs and loses the heel of her shoe in the process. Once they’ve met-cute, the film’s internal clock starts relentlessly ticking; we can almost sense the angels of cinema swooping down to nudge the protagonists toward their inevitable destination. Minnelli orchestrates the remainder of this first encounter in one unbroken take at the top of an escalator, resulting in a funny bit in which Joe tries to go against the flow of the ascending masses to retrieve the missing heel. From this opening, we come to understand the movie as a kind of emotional cartography, one that will chart Joe and Alice’s movements from point A to point B and beyond, from the train station all the way to city hall.

People falling in love onscreen need things to do and memories to make. So it’s lucky for these two that they’ve found each other in one of the greatest cities in the world. (Like In the Mood for Love and Before Sunset, this is a movie that knows how to stage private longings in public spaces.) But The Clock is refreshingly unimpressed by the concrete jungle, most of which is represented by replicas built on MGM soundstages. Obligatory establishing shots show Joe staring up in golly-gee astonishment at a few skyscrapers, but moments later, when reluctant tour guide Alice points out St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the Metropolitan Museum of Art as one might to a distractible child, it’s clear he’s already seen enough. He can’t muster much curiosity about this place, its looming landmarks and cold shoulders.

He’d rather chat, and unlike her, he has limitless patience for small talk. She’s taken aback by his prying questions, but as she keeps humoring him, and as her gazes start to noticeably lengthen, you can tell she’s touched by his guilelessness. It’s not easy to catch a New Yorker off guard, but here she is, surprised by something she can’t quite surrender to just yet. The warm-up phase of their relationship unfolds as a series of transparently false farewells, with her intermittently saying “well, goodbye,” and him responding in such a way that she can’t help lingering a while longer. Each failure to part makes their attraction that much harder to dismiss—and of course reminds us of their inevitable separation when Joe must go back to war.

Minnelli and Garland took on The Clock right after the success of Meet Me in St. Louis, their first collaboration, and shortly before they got married. Although The Clock originated with Fred Zinnemann, whom Garland ultimately deemed inadequate to the high-stakes task of drawing out her first non-singing performance, its resonance with that 1944 musical masterpiece is unmistakable. For a movie in which the bustle of everyday Manhattan threatens to pull the lovers apart, the structure is remarkably tidy: as in Meet Me in St. Louis, the plot of The Clock consists of leanly constructed episodes, each suggesting an anecdote that could be passed on to Joe and Alice’s future grandkids. In contrast to this precise narrative architecture, the tone is fluid, even casual. In the film’s longest sustained passage, centered on a late-night drive with a sweet, middle-aged milkman, the leads are momentarily drowned out by side characters, including a belligerent drunk and a fidgety, lace-hatted dowager he makes a pass at in a diner.

Minnelli’s faithfulness to the modesty of his story is part of what makes the film so overpowering. The looseness of its tone is a perfect match for emotions that can’t be pinned down, that have only just come into being. Though better known for his musicals, Minnelli had an instinctual grasp of the key ingredients of melodrama, those inconvenient, unnamable feelings whose urgency belies the supposed insignificance of their source. You can see the same deftness of approach in the more complicated and feverish dramas he made in the late fifties: Some Came Running (1958) creates its melancholy mood out of a procession of long, meandering hangouts, and Tea and Sympathy (1956) weaves its web of desire around a relationship, between a tormented prep-school senior and the wife of the academy’s coach, that defies categorization.

Like all the best melodramas, The Clock shows us how society is set up to keep our hopelessly ambiguous interior worlds in check. But all you have to do is look at Garland to feel that racing pulse beneath the skin. You notice it in the way Alice keeps flicking the lighter Joe has given her as her patronizing roommate scolds her for giving an unknown man in uniform the time of day. You feel it in how slowly and tentatively she allows herself to fall into Joe’s arms as they share their first evening rendezvous in the deep shadows of a park, a romantic epiphany that rivals the smothering caresses in George Stevens’s A Place in the Sun. Is there another Hollywood star who could inspire as much tender anxiety in viewers as Garland does here? Like few actors before or since, she knew that love is anxiety. What’s beautiful about this performance is that it gives us a chance to see our concern for her mirrored in her concern for someone else, this naïve soldier who finds he’s not in Kansas anymore.

Watching this seventy-five-year-old movie in the devastated New York we’re now living in, I was struck anew by the contradiction on which it hinges. As the end of World War II—the conflict that haunts The Clock from afar—approaches, the city still runs on a few unshakable certainties: the subway doors slam shut whether or not you’ve made it onboard; the milk gets delivered on time; city hall closes on schedule every afternoon. Until they are proven otherwise, the facts of urban life seem immutable. They form an armor of ineluctability in a world where nothing is promised. They forestall the question that floats into the mind during times of indefinite isolation, the same question that Joe and Alice must be asking themselves at the end of the film: Will we ever see each other again?

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.

Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan