Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

From priapic fauns to severed heads: Tate Britain surveys

the artist’s drawings.

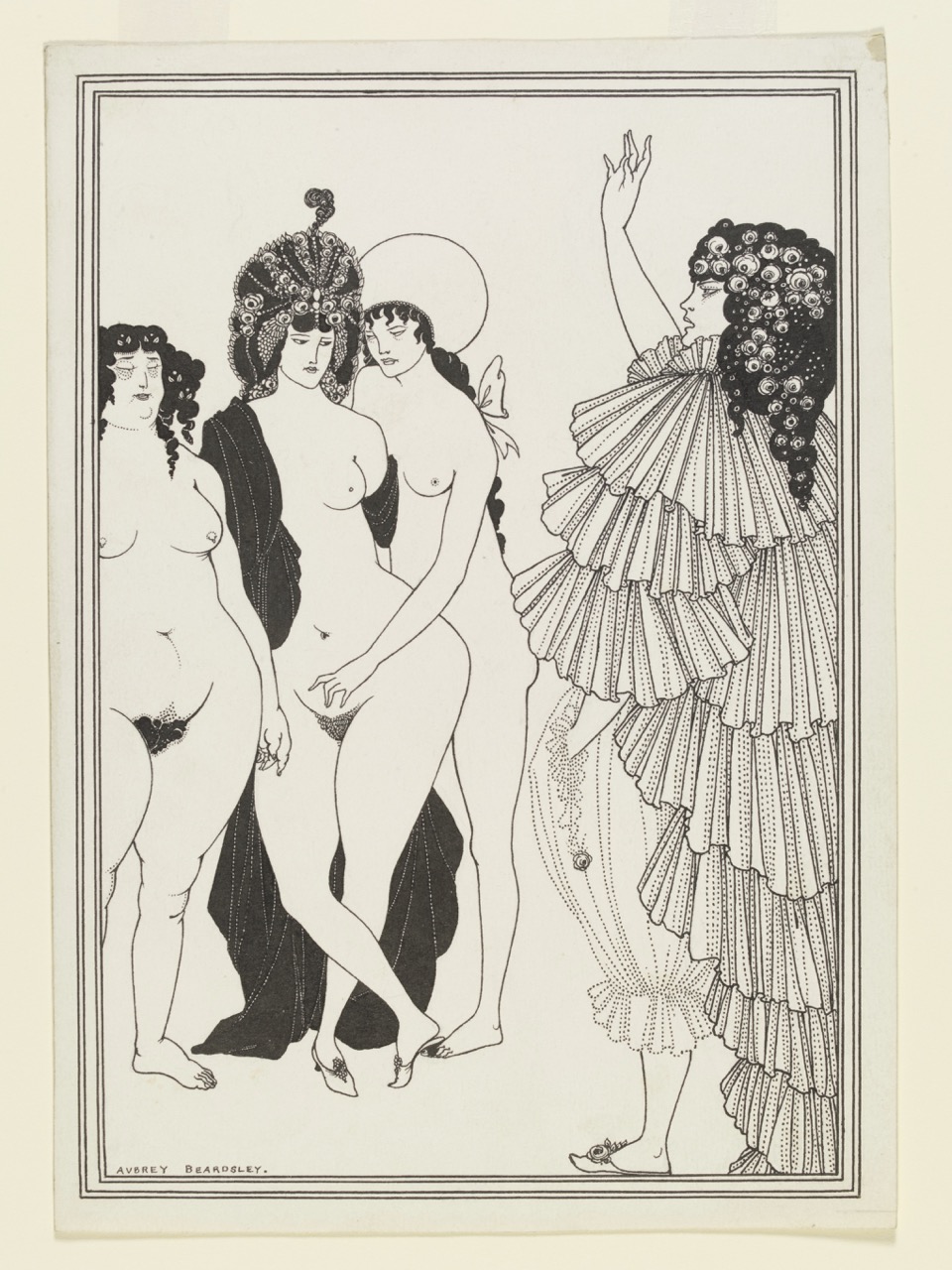

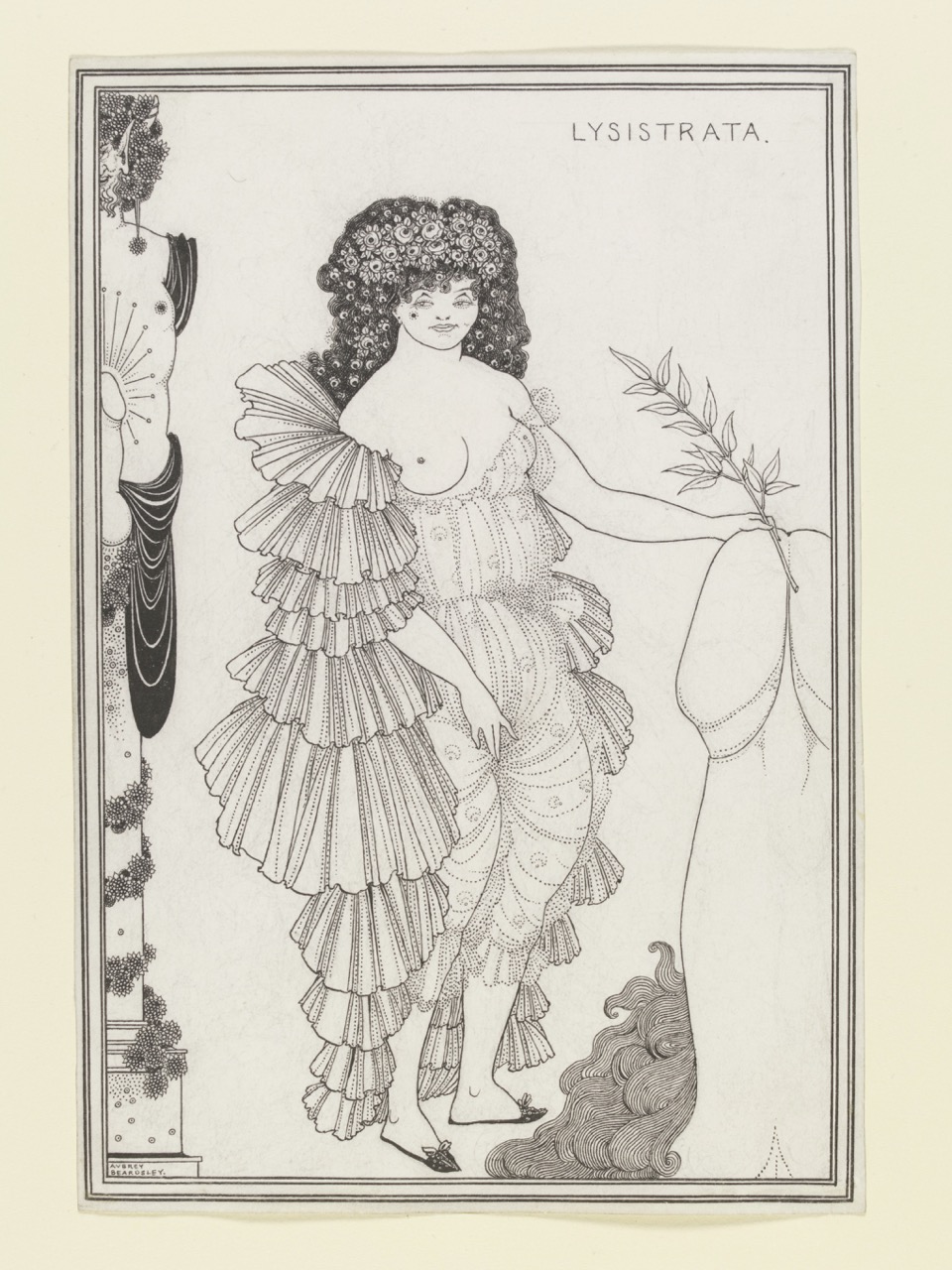

Aubrey Beardsley, Lysistrata Haranguing the Athenian Women, 1896. Ink on paper, 10.8 × 7.64 inches. Image courtesy Tate Britain.

Aubrey Beardsley, Tate Britain, London, through May 25, 2020

• • •

Editor’s note: As of this writing, Tate Britain is temporarily closed to the public due to COVID-19 concerns. A curator-led video tour of Aubrey Beardsley will be available April 13, 2020, on YouTube and on the museum website, which also provides an illustrated exhibition guide and short film about the artist.

• • •

The last time the Tate Gallery (as it was then called) put on an exhibition of Aubrey Beardsley’s work was in 1923, after which his reputation languished, except among callow young men. In 1966, the Victoria and Albert Museum mounted a major show, and on that occasion the eminent art historian Kenneth Clark wrote that Beardsley was “a kind of catmint to adolescents.” The chilly eroticism, the obsessing detail, a certain literary loucheness, and the proliferation of his art in magazines and on posters: Beardsley is decidedly a teenage boy’s idea of an artist—the Escher of his era, and beyond. It was true in his lifetime (he died of tuberculosis in 1898, aged twenty-five) and for decades afterward; even in the 1980s, I recall poring over his lurid drawings at the library. The art world has long found it harder to take Beardsley seriously.

Aubrey Beardsley, How Arthur saw the Questing Beast, 1893. Ink and wash on paper, 14.88 × 10.63 inches. Image courtesy Tate Britain.

One reason, I suppose, is the obviousness of his influences. Beardsley was blatant and shameless in his borrowings, as the Tate Britain exhibition demonstrated before it was prematurely shuttered. (The show was due to run until May 25; at the time of writing, the Tate website still says “closed until further notice.”) The ancient Greeks, Mantegna, Dürer, French Rococo, the Pre-Raphaelites, Whistler, and Japanese scroll paintings—all of it is too conspicuously there. But consider: he was nineteen (and working as a clerk) when he rose to fame for his illustrations to an edition of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur. To the romantic medievalism of his drawings—schooled on the likes of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones—Beardsley added furiously priapic fauns, wildly sinuous lines, and a degree of fine detail (aided by new line-block printing techniques) that looks frankly paranoid, lest any inch of drawing or page should escape significance.

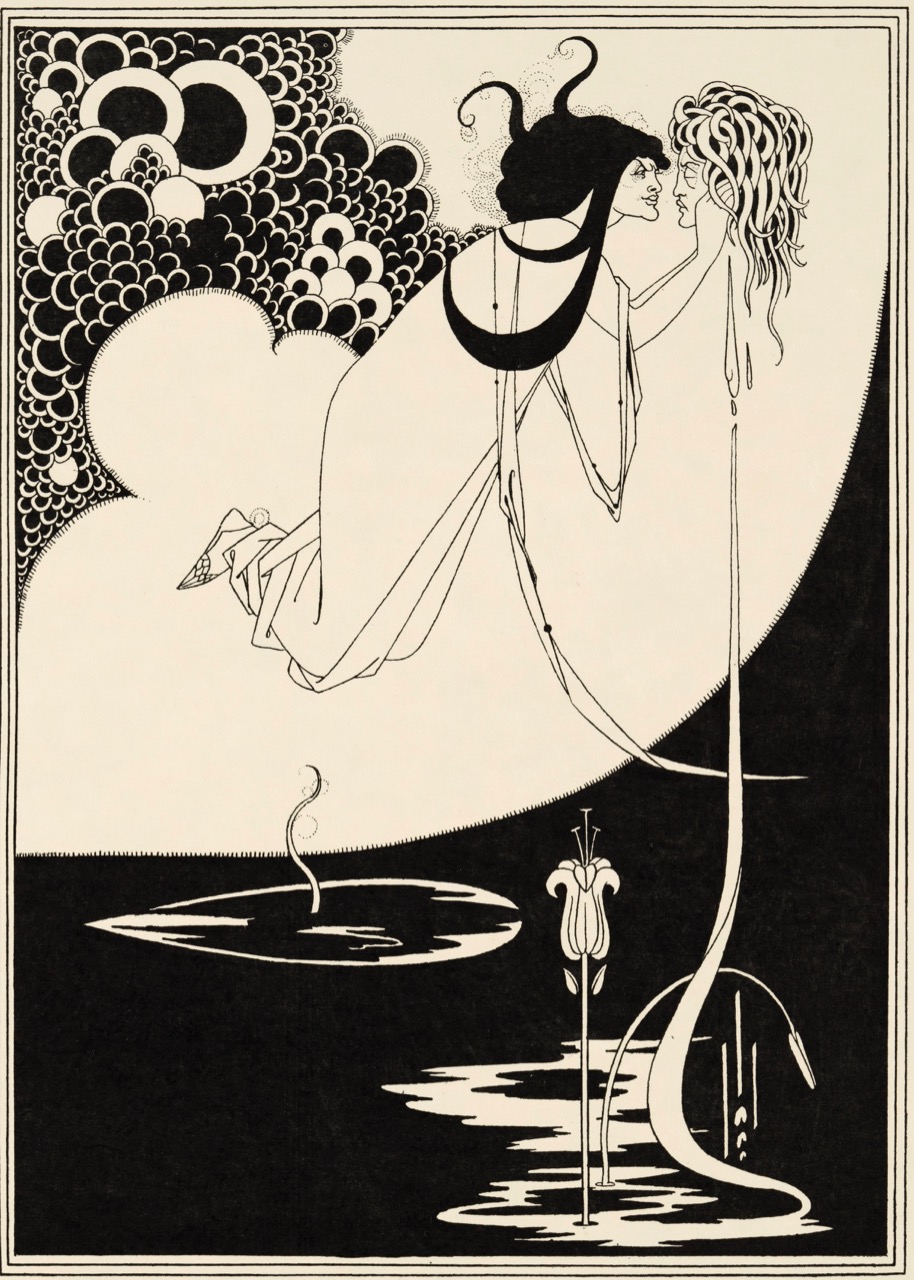

Aubrey Beardsley, The Climax, 1893. Line block print on paper, 9 × 6.42 inches. Photo: © Tate.

In April 1893, an article in the Studio magazine announced the “very remarkable” work of the young illustrator. Commissions poured in. Beardsley wrote to a friend: “I have seven distinct styles and have won success in all of them.” For the piece in the Studio, he had submitted a speculative illustration of Oscar Wilde’s play Salome, which was then banned on stage in England for its depiction of biblical characters. (The Tate show includes one of Wilde’s other sources for the play: the symbolist Gustave Moreau’s queasy, overheated painting The Apparition, 1874–76.) Wilde now came calling, as Beardsley had hoped, on the willowy young artist and dandy. The drawings Beardsley made for the English edition of Salome (all 1893) are probably his best. They combine the narrative intensity of the story—the princess’s malevolent desire for John the Baptist, her grisly triumph as she cranes in to kiss his severed head—with the soaring (or is it phallic?) verticality of every form.

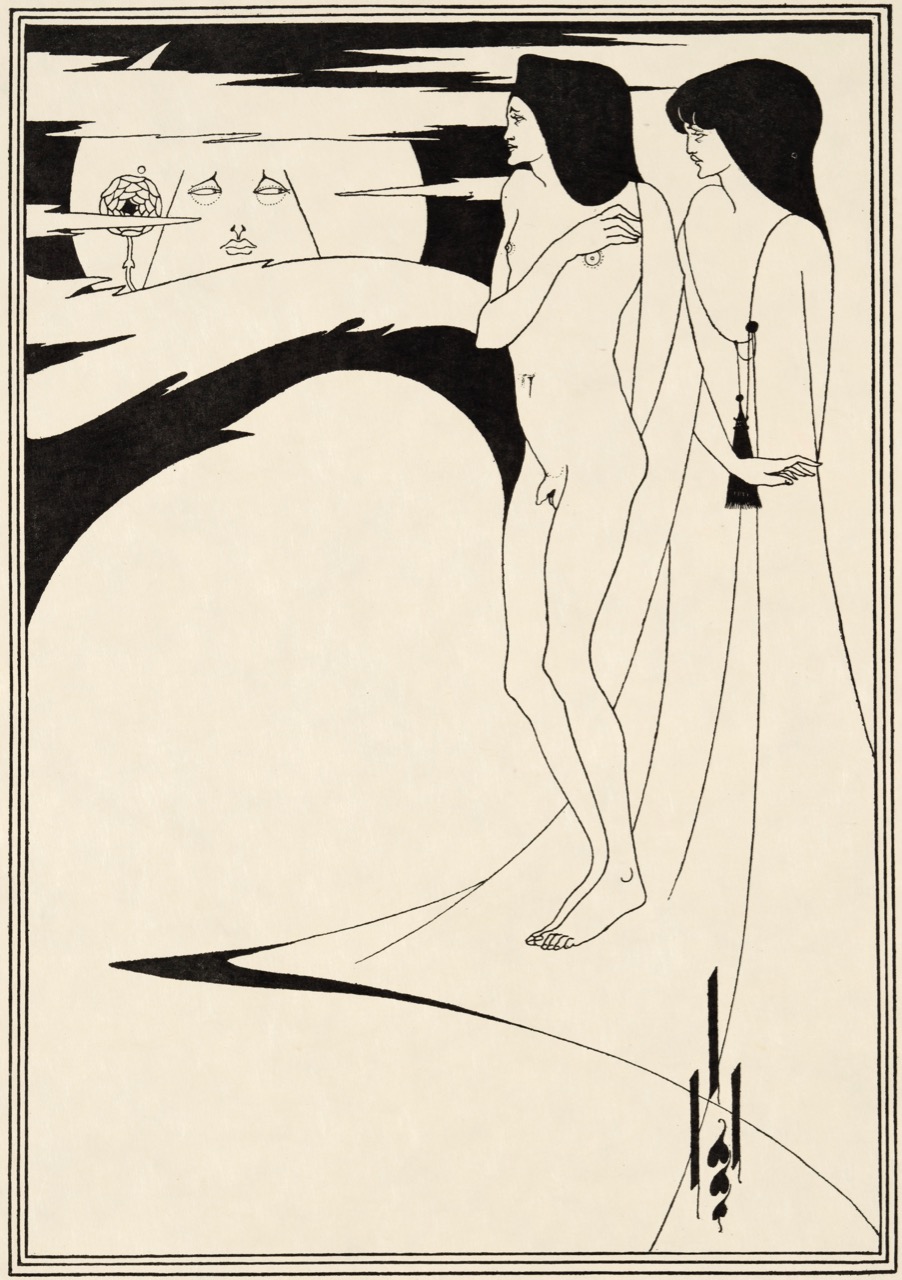

Aubrey Beardsley, The Black Cape, 1893. Line block print on paper, 9 × 6.42 inches. Photo: © Tate.

In places, the Salome pictures approach a sort of vacant abstraction, with Beardsley’s etiolated figures now surrounded by daring amounts of white space, or their black robes and costumes taking over large tracts of the composition. As with the Malory illustrations, some of these images have little or nothing to do with scenes in the play. The most impressive is The Black Cape, which depicts Salome in dress and headgear that look as though they belong in a Dada or Constructivist performance a decade or two later. Formal flair and audacity of subject matter were not the only factors in his Salome drawings: the wunderkind Beardsley realized he had the upper hand professionally in his relationship with Wilde, and took the opportunity to satirize the older man. In The Woman in the Moon, the lunar face in question, at which two characters are gazing in wonder, is not a woman’s at all, but an eldritch, corpulent caricature of Wilde, who found Beardsley’s illustrations even more unwholesome than his own play.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Woman in the Moon, 1893. Line block print on paper, 9 × 6.42 inches. Image courtesy Tate Britain.

Beardsley’s reputation, however, was more closely tied to the writer’s than he thought. When Wilde was convicted for “acts of gross indecency with certain male persons” in 1895, a mob attacked the offices of John Lane, publisher of Salome and the Yellow Book, the decadent periodical of which Beardsley was art editor. Dismissed by Lane, Beardsley (who denied he was a “sodomite”) fled to France, where he coedited a short-lived new magazine, the Savoy, and began to invent, or borrow, new styles. He adopted a frantic, dot-lined mode for pictures based on sexually charged French literature of the eighteenth century, and a sparser design for privately circulated plates to go with Aristophanes’s play Lysistrata (all 1896), which at Tate require their own room and a content warning. In Beardsley’s rendering, the comic tale of a sex strike among Athenian women features huge frustrated phalluses and languid sapphic moments among the strikers.

Aubrey Beardsley, Lysistrata Shielding her Coynte, 1896. Ink over graphite on paper, 10 × 6.8 inches. Image courtesy Tate Britain.

As swiftly as it had all begun, Beardsley’s Icarus flight was over. In his six-year career, he completed more than a thousand drawings and, one discovers at Tate, two rather bad oil paintings: one on the back of the other. His mother had called him “a delicate little piece of Dresden china,” and claimed he was so ethereal he helped himself up a steep flight of stairs using a fern-frond for a walking stick. But what an industrious weakling, racing against the deadline of his disease. According to his friend Arthur Symons, “He had the fatal speed of those who are to die young.” Strange to think of the frenzy of his young art, stilled on the Tate walls right now, shut up along with everything else, cut short again.

Aubrey Beardsley, installation view. © Tate Photography.

The exhibition features over two hundred works, organized around themes that include Beardsley’s influences and early successes, his adventure with Wilde and decadence, his commitment to magazines and posters, the erotic works, and the legacy of his art in popular culture. The show is a rare chance to see Beardsley’s original drawings, including scurrilous first drafts in which he would try to smuggle covert genitals past his publishers. But he lived for the printed page, and so the Tate catalog (with 117 plates and seven essays) is a worthy substitute for the show. It also traces Beardsley’s afterlife in the twentieth century. Following his death, his vogue continued for a decade or so in Britain, Russia, and Japan. (The fact he was such a Francophile perhaps explains why he was not an influence in France—he had borrowed too much.) The 1966 V&A exhibition reminded everyone how trippy his art had been: Beardsley’s is one of the heads at upper left on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. At Tate, the great revelation is a 1923 silent film starring and produced by the Russian-American actor Alla Nazimova. In her Salome, with set and costume designs after Beardsley, she embodies his art: stately, sinister, and a little bit embarrassing.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence will be published by New York Review Books in September 2020.