Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The Leaps of Aesop surveys six decades of the Romanian

avant-gardist’s career.

Geta Brătescu, The Leaps of Aesop, installation view. © Geta Brătescu. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Timothy Doyon.

Geta Brătescu, The Leaps of Aesop, Hauser & Wirth, 548 West Twenty-Second Street, New York City, through December 23, 2017

• • •

I knew I wanted to see this exhibition by Geta Brătescu, the ninety-one-year-old Romanian artist who in the past few years has become an unlikely darling of the global contemporary art scene. But it wasn’t until I was in the gallery—faced with sixty-four works that span sixty years and encompass drawing, animation, collage, film, and books—that I knew how much I needed to see it.

It is always a curious phenomenon when someone who has been practicing her art diligently over a long career is suddenly “hot”—why now? In the case of Brătescu, one must of course consider the ever-voracious market, which seems lately to have developed an enthusiasm for older women (Carmen Herrera, Etel Adnan, and Carol Rama come to mind), and a relatively new art historical awareness of the rich history of Central and Eastern European avant-garde art in the Soviet era. But beyond that, I suspect the ardor has to do with the way that Brătescu provides us with a model for continuing our work in a moment of oppressive politics. As we exhaust ourselves with phone calls to senators and protests and town hall meetings and Facebook debates, as we cope with the mounting anxiety and depression that comes from seeing the daily outrages committed by our government and those around the world in the name of a false, corporate-driven populism, Brătescu is re-energizing, at times outright inspiring. She shows us how to imagine resistance as a form of joy, of play, of grounding ourselves through art. What a challenge, and a gift, that seems right now.

Geta Brătescu, The Leaps of Aesop, installation view. © Geta Brătescu. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Timothy Doyon.

Brătescu studied in Bucharest in the late 1940s until her education was interrupted by the Communist party’s ascent to power. As with other students of bourgeois origins, she was forced to abandon her courses and find a job, which she did—as an office worker, an illustrator and animator, and after some time as arts editor for one of Romania’s most influential cultural journals, Secolul 20 (The 20th Century, later renamed Secolul 21). The magazine was funded by the Romanian government but operated relatively autonomously, becoming a bastion of enlightened thinking. The Communist regime, even at its most repressive, understood there to be a value in being seen as innovative and forward-thinking in the arts; it allowed an avant-garde to exist as a sort of “open secret,” tolerated or censored by turns depending on the political climate. In the late 1960s, in a period of relative openness, Brătescu was able to resume her fine arts degree and become a member of the Artists Union, which meant she was able to obtain a studio and travel outside the country to see and document art exhibitions. From the 1970s forward, and especially after the fall of Ceaușescu’s government in 1989, Brătescu was a reliable, beloved presence in the Romanian art scene, if hardly a star, according to the exhibition’s curator, Magda Radu. (Radu also organized Brătescu’s showing in the Romanian pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennial, an event that catapulted the artist to international art world fame.)

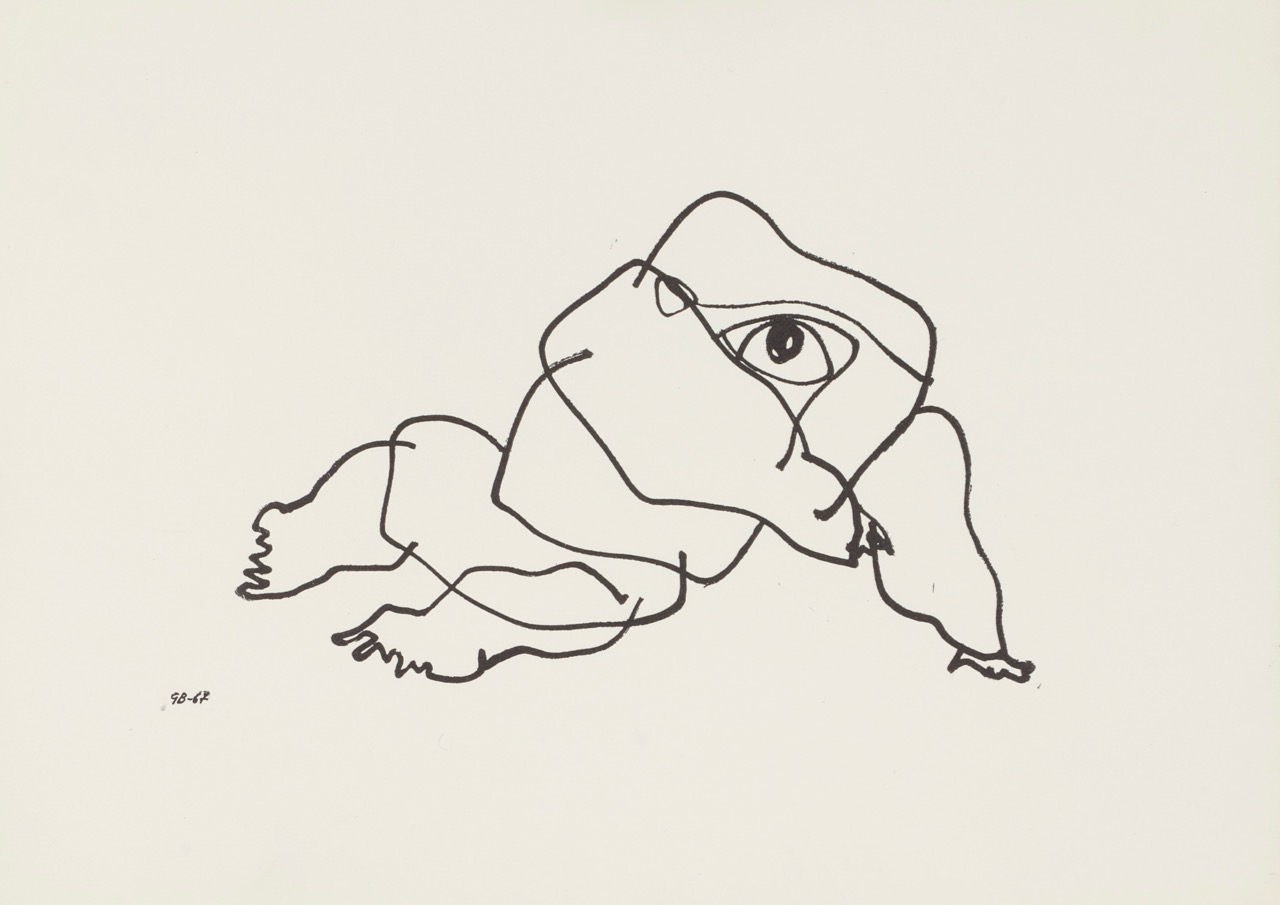

Geta Brătescu, Esop (Aesop), 1967. Detail. Series of 10 lithographs, grey ink on paper. © Geta Brătescu. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ștefan Sava.

The earliest pieces in the show, dating from 1967—a drawing book filled with images nimbly rendered in an energetic, continuous line and an animated film (along with the ink-on-acetate cels involved in its production)—center on the figure of Aesop. Indeed, the ancient Greek fabulist is both an object of Brătescu’s study and a kind of guiding principle for her own artistic persona. According to legend, Aesop was a Greek slave, famously ugly and malformed, who both impressed and undermined his master with his charm, playfulness, and clever way with words, seducing his master’s wife and making him look a fool, eventually winning freedom for himself. He represented, as Brătescu once said, “everything that came to stand against totalitarianism,” perhaps not least because he offered the possibility of oblique and subtle subversions when direct political critique was simply not feasible.

Geta Brătescu, Ionesco—The Clown, 1971. Photograph and collage, 9 3/8 × 7 3/8 inches. © Geta Brătescu. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ștefan Sava.

Aesop’s spirit permeates Brătescu’s work, even when he himself isn’t pictured. Sometimes he appears in other guises, as in Ionesco—The Clown (1971), a doctored photograph of the famous playwright, or in the drawings and prints she did of other tricksters, including a 1974 series of woodcuts of Nasreddin Hodja, a Middle Eastern character who shares some folkloric DNA with Aesop himself. At other times, his presence is felt only as a disruptive spark, most delightfully in Brătescu’s proposition for a public artwork, Magnets in the City (1974), in which U-shaped magnets would be placed around a metropolis—massive ones in a field outside town that would attract metal objects from the pockets of passersby; medium-sized ones in squares and roundabouts for city dwellers to arrange and rearrange, potentially rerouting or blocking traffic as random household objects like teapots and saucepans haphazardly accumulate on them like barnacles; and small ones in children’s playgrounds and schoolyards. The goal of the project, states Brătescu in the accompanying text, is to turn the city into a studio—a site for art—as well as to encourage city dwellers to understand how force works, how to operate in relation to it, how to manipulate it.

Geta Brătescu, Magnetii in Oras (Magnets in the City), 1974. Detail. Photographic montage. © Geta Brătescu. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Mihai Brătescu.

Brătescu channels Aesop’s ludic spirit in two films on view, The Studio (1978) and The Hands (1977), both done in collaboration with Ion Grigorescu, a well-known figure in the Romanian avant-garde. In the former, the camera follows her from waking through the first hours of the day, during which she takes part in an absurd, ritualistic form of play with her surroundings and its contents. In the latter, she focuses her attention on her hands, which become both the subject and the object of her mark making as she traces them on paper, draws their bony structure on her skin, and so on. The artist’s creativity is contained by the studio, the artist’s work is bounded by her body—this inward turning seems at once descriptive (how does one operate in an authoritarian state?) and incredibly freeing.

Geta Brătescu, Jocul Formelor (Game of Forms), 2012. Series of 7, collage on paper. © Geta Brătescu. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ștefan Sava.

The same goes for Brătescu’s pragmatic approach to materials, using whatever is available (scraps of fabric and cardboard, cigarette papers, yogurt cups, and so on) to fashion her marvelous objects. Books can be humble paper accordions with repeated shapes (Memory VI, 1990, Déjeuner sur l’herbe, c. 2006). Drawings can come into being with a mere scissor’s cut (her series Game of Forms, 2010–15, Magic Form, 2009). Masklike “portraits” can be created merely by molding wet paper on a bowl (Mothers, 2004). Her most abstract works, which have earned her fame in recent years—collages based on a few geometric shapes deployed in myriad, endlessly inventive combinations—emerged in the 1980s, during a period of harsh repression by the government. At the point that many of us are feeling a bone-numbing political exhaustion, Brătescu gently reminds us that we have no good excuse to throw in the towel. Making art can be a simple process of making do, within whatever political and material constraints exist at the moment—and, at certain moments in our history, making do can be a triumph all its own.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and the Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson, and another book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, will be published by Badlands Unlimited in spring 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.