Ed Halter

Ed Halter

No more Godard remakes! The Museum of Modern Art looks back at a key era in the East Village underground via its films.

Monster Movie Club at Club 57, 1979. Photograph by and courtesy Christina Yuin.

Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983, the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through April 1, 2018

• • •

We often speak of a downtown scene, yet rarely stop to dig up the roots of that petrified metaphor: of the scene acted upon a stage, the scene as setting for a narrative. Herein lies an underlying lesson of the Museum of Modern Art’s Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983, which uses the history of the eponymous venue to focus on post-punk New York’s clamorous, late-bohemian network of artists, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, publishers, impresarios, and otherwise uncategorizable personalities. Club 57 existed at a time when the core of social life took place in public rather than mediated through digital avatars; thus the curatorial operations of the space, as well as the variegated aesthetics of its habitués, prove self-conscious enough to be historicized as a kind of collective, ongoing performance, something like the neon-haired aftermath of an older underground’s attempt to dissolve the borders between art and everyday life. So while MoMA’s Titus galleries do contain some painting and sculpture, the real energy in these rooms springs from the Xeroxed and collaged flyers, posters, and zines marking events held at the spot (which was located in a Polish Catholic church basement at 57 St. Mark’s Place, retooled to minister to a rather different congregation of souls).

Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983, installation view. © 2017 Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt.

Fittingly for a show primarily devoted to understanding events rather than objects, the largest portion of the exhibition itself is ephemeral, consisting of four different screening series, each of which could stand as a substantial program on its own. There’s a weekly selection of videos in the galleries, presenting music videos, cable TV shows, performance documentation, and other Club 57–related media items. These are projected in an exposed situation, pervious to the interruptions of passersby—a cleverly delivered microdose of the much rowdier atmosphere in which films were shown at the club. “You Are Now One of Us: Film at Club 57” re-creates the repertory programming that ran there, which leaned hard into ’60s mod and old drive-in fare that would have held rich camp-nostalgia value for a generation born under Eisenhower and Kennedy. Toward the end of the exhibition this spring, London’s concurrent club life will be considered alongside New York’s via the imported program “This Is Now: Film and Video After Punk 1978–1985.”

Somewhat more perpendicular to Club 57’s history is the series “New York Film and Video—No Wave–Transgressive,” the title of which refers to two partially overlapping movements that grew out of Lower Manhattan during New York’s most economically drop-dead period, roughly the late 1970s to the early 1990s: No Wave Cinema and the Cinema of Transgression. The former category refers to a group of filmmakers associated with the short-lived New Cinema, located just down the block from Club 57, a good number of whom—Vivienne Dick, Eric Mitchell, James Nares—were European émigrés who collaborated with the No Wave musicians of the moment. Filmmaker Nick Zedd first named the Cinema of Transgression in 1985 to describe a somewhat different circle of artists, including Zedd, Richard Kern, Tessa Hughes-Freeland, and others. There are important differences between these two scenes—No Wave Cinema gravitated toward feature-length storytelling, influenced by Godard and Warhol, while the Cinema of Transgression tended toward shorter, more aesthetically aggressive films, frequently punctuated by sex and gore.

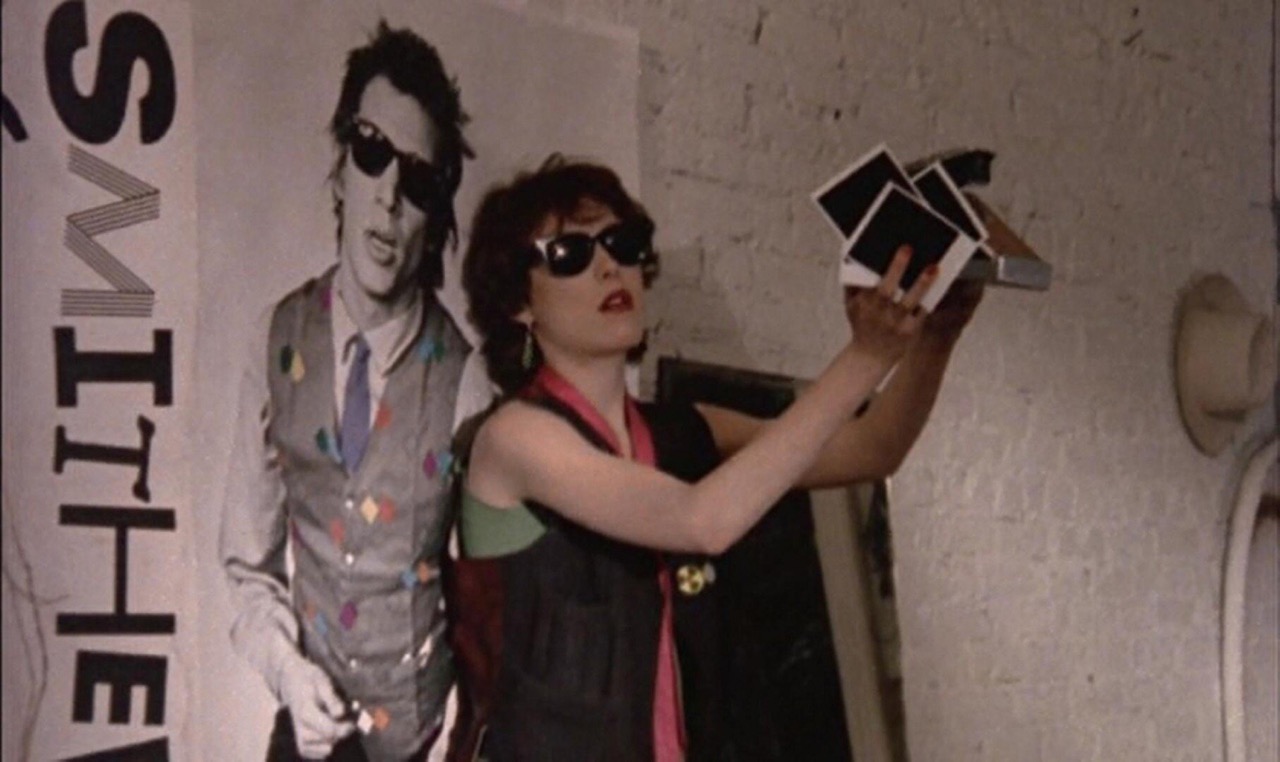

Susan Seidelman, Smithereens, 1982. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

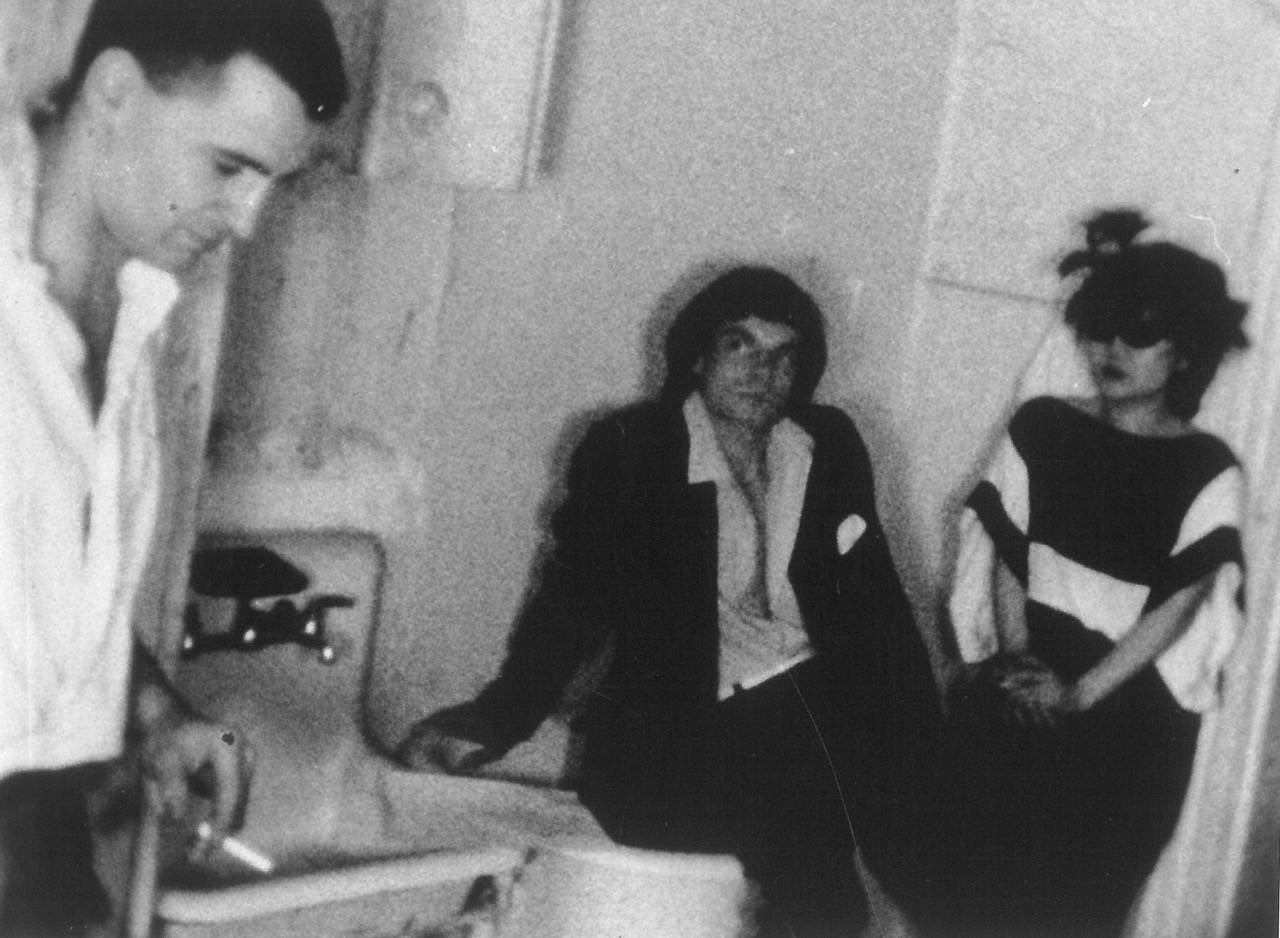

In retrospect, however, the affinities between the two factions seem greater than their differences, and MoMA’s slightly awkward series title indicates the need for a single descriptor for an urban aesthetic that now seems as distinctive as film noir. The blend of documentary and scripted fiction, acting and non-acting, gritty realism and goofy parody easily connect the quasi-pornographic, monster-movie-influenced vibe of the Cinema of Transgression with No Wave Cinema’s graffiti-backdropped, sub-arthouse storytelling; both movements employed low-budget 16mm and no-budget Super 8 formats, often completed and exhibited on video, to produce fuzzy media hybrids that make Hollywood’s Poverty Row movies look lavish in comparison. From Susan Seidelman’s well-told punk-feminist picaresque Smithereens (1982), to Mitchell’s Kidnapped (1978, a guitar-driven redux of Warhol’s Vinyl), to Kern’s violently comedic nuclear family meltdown You Killed Me First (1985), the films in this series celebrate characters who embrace prostitution, drug-dealing, homelessness, and even murder as a given of downtown existence, portraying their own era as one in which living the life of an artist means becoming part of the urban underclass. One of the scene’s origin myths is the story of “Nick the Fence,” a streetwise entrepreneur who jump-started this new epoch in filmmaking by unloading a stash of hot Super 8 cameras at sixty bucks a pop.

Eric Mitchell, Kidnapped, 1978. Image courtesy the filmmaker.

MoMA is not the first venue to celebrate this tendency; since the period became canonized in 1996 with the Whitney Museum’s exhibition No Wave Cinema 1978–1987, it’s been revisited multiple times by the institutions of gentrified Gotham. Many of the titles showing as part of “No Wave–Transgressive” have been screened as recently as 2015 as part of the Museum of Art and Design’s “No Wave Cinema” and Anthology Film Archives’ preservation series “Re-Visions: American Experimental Film 1975–90.” But there are important rediscoveries here as well. One seldom-seen entry is Becky Johnston’s Sleepless Nights (1978), a hard-boiled Super 8 narrative shot in extreme chiaroscuro, still containing zaps of analog-video distortion even after its digital restoration. Johnston’s feature highlights how abject punkdom provided better opportunities for women filmmakers at the time than the industry, as do Smithereens and Rachel Amodeo’s What About Me (1989–93), a late-underground entry that plays like a grimmer update to Seidelman’s tale of female vagabondage.

Harald Vogl, Dear Jimmy, 1978. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Even rarer is the work of Harald Vogl, an Austrian-born director and part of the New Cinema crowd, who produced a string of four potent Super 8 features from 1978 to 1984 that likely haven’t been seen for decades. Vogl’s rangy films showcase many members of the social network who reappear throughout the underground movies of the time, including squeaky-voiced artist David McDermott, New Wave it-girl Patti Astor, musicians James Chance and Pat Place. In Dear Jimmy (1978), Vogl shows Mitchell directing, and pokes fun at No Wave Cinema’s nouvelle vague influences: “No more fucking Godard remakes,” declares one character in the film’s opening. In later projects, Vogl veers deeper into true documentary than most of his peers ever did, including wordless stretches of everyday street life in OK Today Tomorrow (1982) and a trip to Washington, DC, to visit the then-new Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Measure Taken (1984). In that film, footage of protests connects the dots between the cinematic subversions of Vogl’s peers and the political undertones of the No Wave pose. “Ronald Reagan is no good,” the demonstrators chant. “Send him back to Hollywood!”

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. He is the recipient of the Thoma Foundation 2017 Arts Writing Award in Digital Art for an emerging arts writer, awarded by the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation.