Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The artist composes a complex revision of Harlem’s

National Memorial African Bookstore.

Leslie Hewitt: Reading Room, installation view. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarelli. Image courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

Leslie Hewitt: Reading Room, Perrotin, 130 Orchard Street,

New York City, through October 26, 2019

• • •

Leslie Hewitt’s work has long been involved in resisting the simple seductions of the past—or, to be more precise, in finding ways to engage history without imagining that it is possible to reenact its greatest triumphs in our very different present. How to remember without becoming nostalgic or turning the past into a fetish? These questions animate Hewitt’s exhibition Reading Room at Perrotin’s space on the Lower East Side.

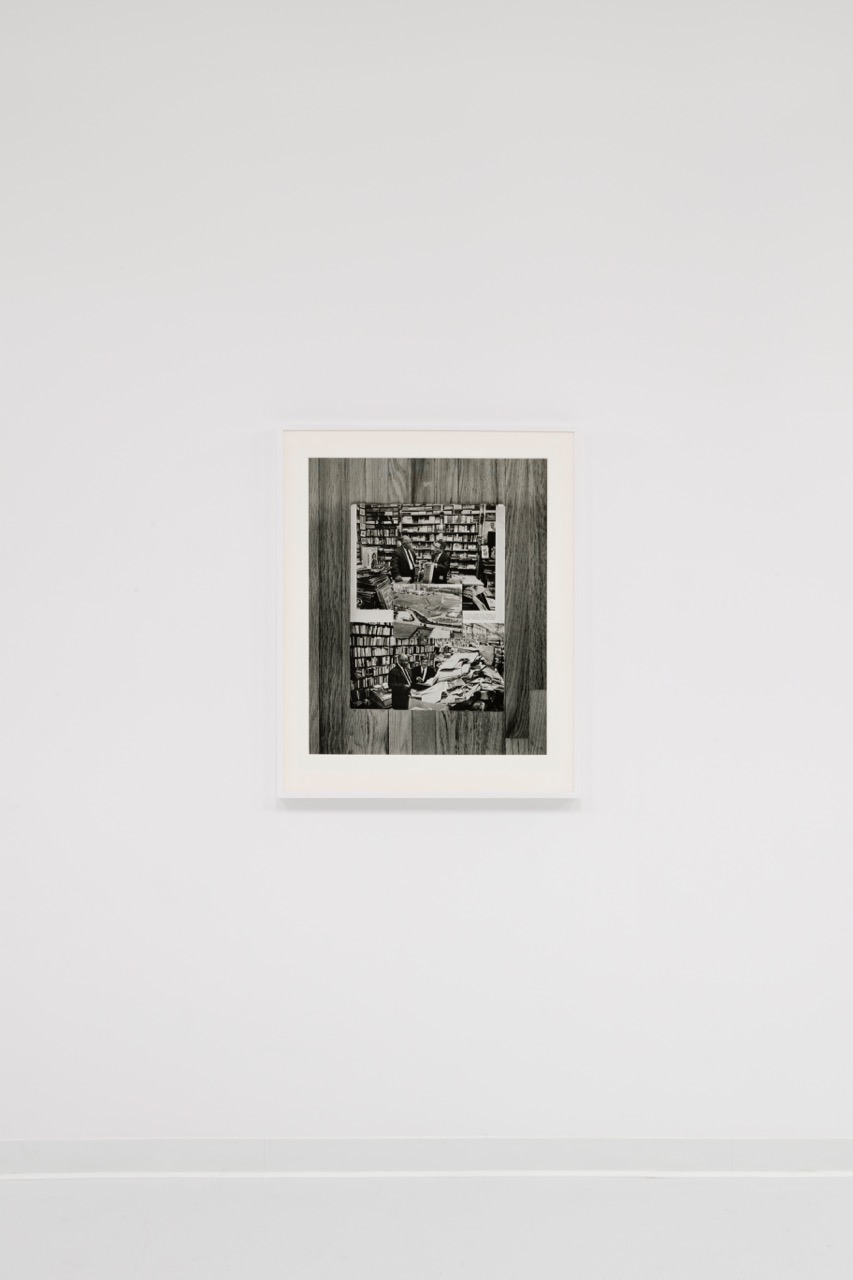

The beating heart of the show is located in the gallery’s annex-cum-bookstore, where a framed gelatin silver print, the second of ten from her series Riffs on Real Time (2012–17), hangs on the wall. The photograph is constructed of layers—the wide strips of an oak floor, on top of which sits the page of a magazine, on top of which lies a found aerial snapshot of a helicopter landing field. The torn-out page contains a story about the National Memorial African Bookstore, a hub of Black intellectual and political life in Harlem founded in the 1930s by Lewis Michaux. At its height, the shop packed over 200,000 books onto its groaning shelves—books by and about African Americans, Africans, and others of the Black diaspora—and was a regular stop for figures like Kwame Nkrumah (who became Ghana’s first president), Malcolm X, Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, and other authors, activists, and scholars. It closed in 1974, a few years before Hewitt was born.

Leslie Hewitt, Riffs on Real Time (2 of 10), 2012–17. Gelatin silver print, 37 3/4 × 30 3/4 inches. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarelli. Image courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

Here and in the next room, Hewitt has created an imaginative reconstruction of the National Memorial African Bookstore—not a simulacral re-presentation of the past but rather a rebuilding of it in different visual and material languages, in a manner that is as much about what we cannot see or experience as it is about what we can. Hewitt never tries to picture the shop, the community who gathered there, or the larger political field in which it was embedded (even the photos contained in the magazine layout in Riffs on Real Time [2 of 10] are partially obscured). Rather, in a variety of media and forms, she attempts to map the conceptual possibilities opened up by knowing about this lost and treasured space.

Leslie Hewitt: Reading Room events poster. Image courtesy the artist.

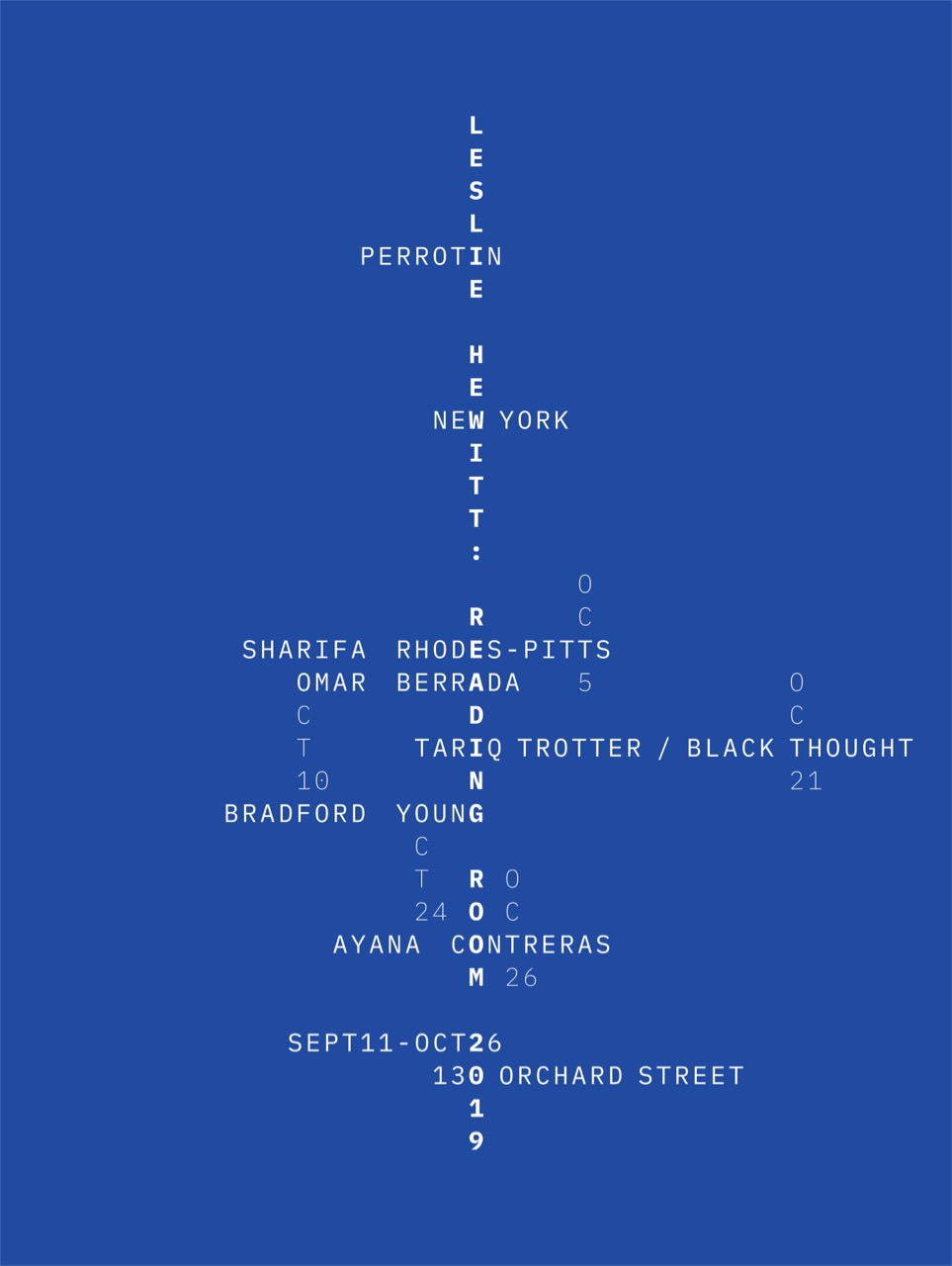

Across from Riffs on Real Time (2 of 10) are the metal bookshelves that normally house Perrotin’s stock; Hewitt has filled one very long shelf and part of another with an array of writings that inform her approach to history and visuality. The selection includes works by Du Bois, Hughes and Roy DeCarava, Fred Moten, Harun Farocki, Hito Steyerl, Jacques Rancière, and others; topics range from theories of the photographic and cinematic image to histories of protest and Black liberation to concrete poetry to Korean painted screens and Dutch still life. This collection will be supplemented, over the course of the show, by a number of events—readings, performances, and conversations featuring curator/writer Omar Berrada, DJ/collagist Ayana Contreras, historian/writer Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, cinematographer Bradford Young, and musician Tariq Trotter / Black Thought. (Striking blue posters announcing the schedule sit in a pile, Felix Gonzalez-Torres–style, on the floor nearby.)

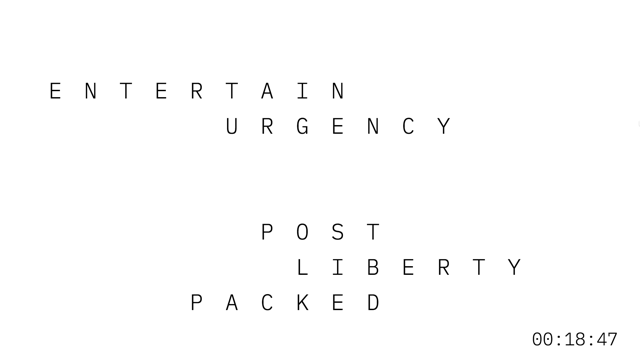

Leslie Hewitt, Forty-two, 2019 (still). 42-minute-long technoscape film. Image courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

The eclecticism of texts, voices, and ideas on display here points to the capaciousness of Hewitt’s thinking. It also alludes to her belief that looking at visual images is a form of reading, and that reading is a form of collective practice. This theme emerges most compellingly in the video Forty-two (2019). Running for exactly as many minutes as the title of the work, which itself refers to the number of years the National Memorial African Bookstore existed, the piece is in fact a concrete poem—a genre that conflates reading and looking, forcing us to see words in their spatial disposition on the page or, in this case, on the screen. The words in question here are the product of Hewitt’s research into Michaux’s shop, gleaned while looking closely at extant images of the site; they come from the volumes visible in archival photos or from the artist’s thoughts while she was poring over these documents. After amassing over a thousand words via this process, she worked with programmers to build a machine, using a 1960s coding language, that would arrange and rearrange them on the screen, resulting in an abstract, but still lyrical, homage to the place. (The gridded poems are interrupted at intervals during the video to reveal the underlying programming language.) In Hewitt’s installation, we are being offered access to the past, but one that has been translated in multiple ways in its path to the present.

Leslie Hewitt: Reading Room, installation view. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarelli. Image courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

A series of framed photographs and a group of five powder-coated steel sculptures in Perrotin’s main gallery continue the artist’s dismantling of clear-cut dichotomies. Drawing on the art historical tradition of the still life, the photos (or photo-sculptures, as the artist terms them) all depict a square wooden panel leaning against Hewitt’s studio wall, perched on a pile of paperback books; the careful arrangements often include other found or created objects (snapshots strewn on the oak floor in front, torn photos tucked between wall and lumber, chunks of onyx or obsidian, a conch shell, an abstract ink drawing made by the artist, a brass Möbius strip, also made by the artist). The books on which the wood panel is set are mostly stacked with their spines to the wall, but in a few cases you can see that the pile includes Jean-Paul Sartre’s Black Orpheus, Henry Dumas’s Ark of Bones, or both.

Leslie Hewitt, Untitled (Cornucopia), 2019. Digital chromogenic print in custom elm frame, 52 3/8 × 62 3/16 × 7 1/16 inches. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarelli. Image courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

With their substantial elm frames and their disposition (they also sit on the floor, leaned against the walls), the works blur the distinction between image and object—they are not simply photographs of still lifes, but photographs as still lifes. They speak to the possibilities of the medium as both a mechanism for seeing and a tool for occlusion—their crisp, almost impossible clarity promising a kind of visual access that is then countered by the obdurate wood panel, which itself functions in the dual role of stopping our gaze and offering us a space for imaginative projection.

Leslie Hewitt: Reading Room, installation view. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarelli. Image courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

Reading, as the philosopher Rancière reminds us in “The Ignorant Schoolmaster,” is itself merely a form of deciphering images—the ability to recognize an e as different from a c or an o. Hewitt’s practice seems to hinge on a similar observation. The succession of photos, with their minor shifts of arrangements, objects, light and shadow, forces us to slow down, to make sense of their minute variations the way we might a text. The bent and folded metal sculptures that lie on the floor at the center of the room also engage this notion of seeing-as-reading but operate in the opposite direction. Each of them seems radically different, and in their somewhat random, even slightly chaotic arrangement they counterpose the photographs’ careful geometries—that is, until you recognize that each is made of the same three-by-six-foot rectangle. Theme and variation are held in such tension in the works here that their analogues—similarity and difference, but also present and past, or historical and contemporary—are rendered simultaneously nearly imperceptible and yet hugely significant. In Hewitt’s complex revision of the National Memorial African Bookstore, the place is evoked at every turn and yet held at an irrevocable distance, as if to underline the point that the chasm that separates us from it is both infra-thin and vast. But that chasm is, in Hewitt’s subtle and delicate eye, where meaning lies.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her book Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is editor of the forthcoming Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2019), and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.