Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Police algorithms, art molecules: a group exhibition interrogates technology and control.

Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown: Kabous, The Left Witness and The Right Witness, 2019 (installation view). Photo: Dan Bradica. Image courtesy the Shed.

Manual Override, curated by Nora N. Khan with Alessandra Gomez, the Shed, 545 West Thirtieth Street, New York City, through January 12, 2020

• • •

One of my most vivid childhood memories involves peeking out from under a blanket in the back of my parents’ station wagon at the drive-in to surreptitiously watch a movie I was definitely not supposed to see: Westworld, the 1973 Michael Crichton dystopian sci-fi flick in which cosplaying robots at an upscale theme park get a computer virus and begin killing the guests. (Yul Brynner was the most murderous of these machines.) Backup systems fail and no one knows what to do, in part because the androids have been built by other androids—their mechanisms are opaque even to the technicians supervising them.

This nightmare scenario—and trust me, even at age three it was the stuff of nightmares—informs an exhibition now up at the Shed, Manual Override, curated by Nora Khan, and including work by Morehshin Allahyari, Simon Fujiwara, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Sondra Perry, and Martine Syms. Just as our digital worlds offer increasingly sweeping (if dubious) promises—a future of quasi-utopian pleasure; methods of organizing society according to objective data analysis rather than flawed human judgment—they have become progressively more complex and impossible to conceptualize. Manual Override raises the troubling questions of how much we control these technological systems and how much we are controlled by them, how much they permit us to transcend our fallible humanity and how much they reinforce our worst tendencies to oppress and control others.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, The Electronic Diaries, 1984–2019 (installation view). Photo: Dan Bradica. Image courtesy the Shed.

The art of Hershman Leeson, who has been working diligently since the early 1980s to explore and unmask the ways technology shapes our experience of the self, is the hub around which the show revolves. Her six-screen installation of excerpts from The Electronic Diaries (1984–2019) feels almost unbelievably contemporary: when camcorders first became available in the 1980s, she started recording her most private thoughts, anticipating by decades the confessional vlogs and Instagram live streams that have become so familiar. Her stories—of unsated hunger and body dysmorphia, divorce, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and much more—are intimate, yes, but she constantly reminds us of their mediated nature, sometimes intercutting them with news images or interviews with friends and collaborators. Around 1993, she began taping conversations with scientists and medical ethicists about topics such as emerging gene-editing techniques and DNA digital storage (the ability to embed massive amounts of information in a gene strand). These discussions are both optimistic and terrifying: we hear the unbridled belief of scientists that technological change will improve and extend our lives by offering new, powerful tools and therapies, as well as cautions about how such advances might be exploited by eugenicists and the surveillance state.

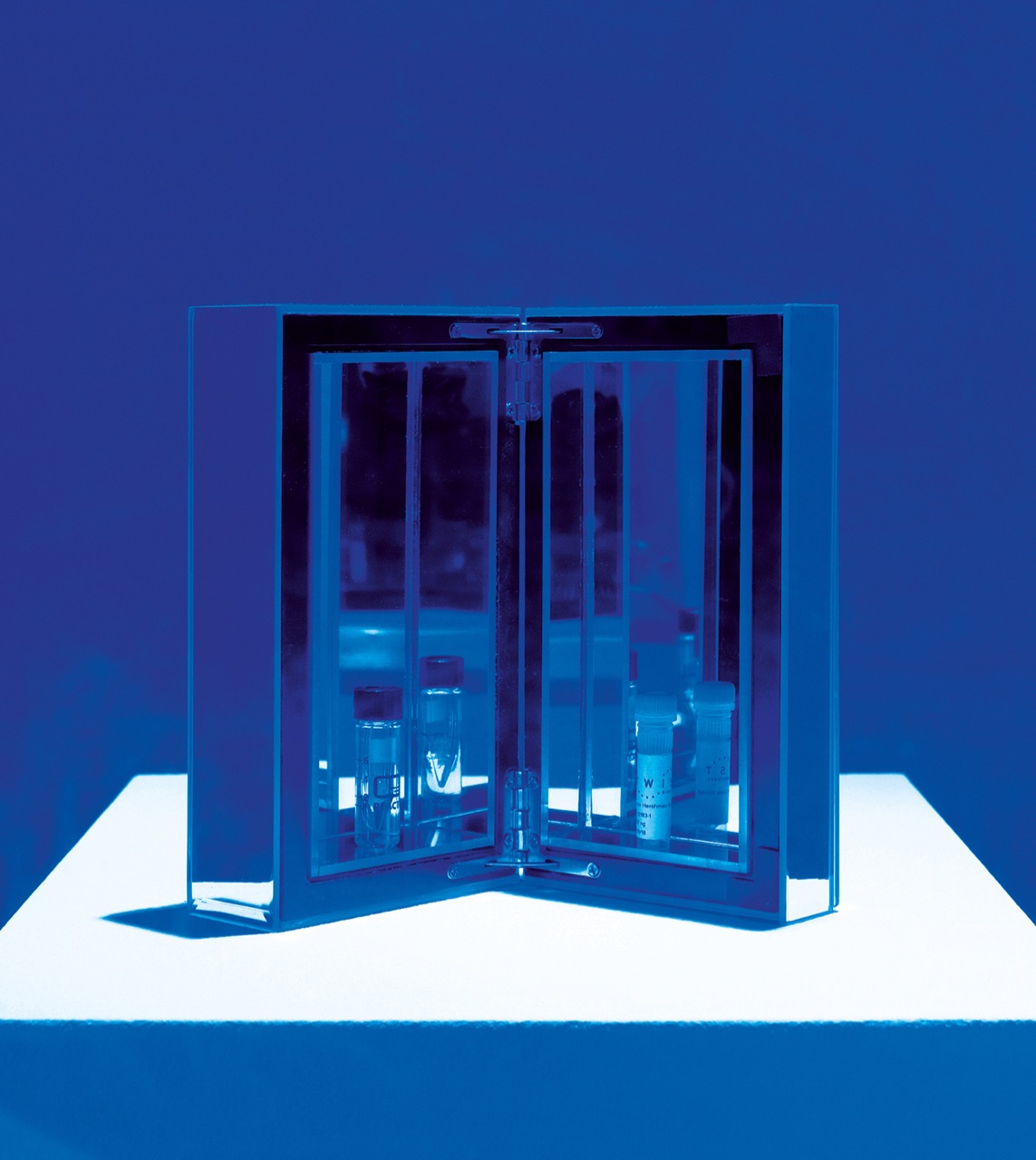

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lynn Hershman Leeson DNA and Antibody inside Room #8 from the Infinity Engine series, 2018. Photo: Franz Wamhof. Image courtesy the artist, Novartis Pharma AG, Twist Biology, Bridget Donahue Gallery, and Anglim Gilbert Gallery SF.

What the artist does in the face of the knowledge gleaned from these exchanges is demonstrated a few steps away. Room #8 (2018) consists, in part, of a glassed-in, secured lab case containing two vials—one holding two decades’ worth of the artist’s research written on a DNA molecule in binary code, and the other a bespoke antibody, created with the help of the pharmaceutical firm Novartis, that uses the letters of her name as the basis of its molecular makeup. Both interventions resist the nefarious potential applications of the biotechnologies she deploys: instead of passively allowing her gene material to be read by others, she is inserting her own reading material into it; instead of waiting for scientists to create antibodies in response to emerging threats, she proactively fashions one on the basis of an arbitrary marker of her identity.

Simon Fujiwara, Empathy 1, 2018 (installation view). Photo: Dan Bradica. Image courtesy the Shed.

Other artists in the exhibition take up the implications of Hershman Leeson’s work in various ways: Perry connects our technological present to longer historical and material processes, Syms explores the mechanization of intimacy in an algorithmic environment, and Allahyari questions the border between virtual reality and the dreamspace. Fujiwara’s Empathy 1 (2018) highlights the exceptionally mediated nature of twentieth-century empathy, and asks us to attend to the ways our current digital environment demands that we submit to control “in exchange for fleeting, concentrated pleasures” (as with, for example, the way we are obligated to sign away our privacy in order to watch cute cat videos on Facebook). In an outer reception area, you may read legal disclaimers and medical warnings about what you are to experience and peruse copies of Fifty Shades of Grey—a book premised on a young woman’s agreement to give up her freedom in order to enter into a world of luxury and sex with a domineering lover. You are then led, along with one other person, into a room and belted into raised chairs without the slightest idea of what is to come. The experience is hard to describe without spoilers, but it was created in collaboration with theme-park designers; the chairs swoop, jerk, and glide in concert with the first-person viewpoints of wildly disparate, found YouTube footage. By its end, you wonder how much this exercise of seeing the world through someone else’s eyes engenders empathy with a person, or with the camera itself.

Simon Fujiwara, Empathy 1, 2018 (installation view). Photo: Dan Bradica. Image courtesy the Shed.

Ultimately, one of the most interesting aspects of the show comes in the form of a “glitch”—a moment when even the most carefully devised technological systems don’t work as planned. Hershman Leeson’s Shadow Stalker, newly commissioned for this exhibition, has multiple components, all focused on the troubling use of digital algorithms by the police—including a film narrated by Tessa Thompson, star of the HBO reboot of Westworld, which explains how such methods often reinforce, rather than reduce, bias against people of color and the poor. Elsewhere, a screen summons you to enter a US zip code to see the likelihood not of violent crimes, as one might expect given the technology’s normal use by law enforcement, but of white-collar, financial offenses. (Manhattan’s Upper West Side has a 100 percent probability of such misdeeds taking place.) An iPad lets you test out how predictive policing software works—you punch in your data and a projected outline of your body on the adjacent wall fills with information about you culled from the internet and from facial-recognition devices. When I did it, I was both relieved and amused at the results: yes, it discovered the name of my ex-husband, but I have not been to Topeka, nor was I born in 1968.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Shadow Stalker, 2019 (installation view). Photo: Dan Bradica. Image courtesy the Shed.

This glitch was not intended by the artist, but nor does it strike me as a “failure” of the artwork per se. It’s a sign, on the contrary, that however powerful and inscrutable our technological environment is, it is not yet foolproof. There is a comfort in this, just as there is comfort when Facebook’s reputedly omniscient algorithm serves me up ads for video-gaming chairs and upcoming Jordan Peterson lectures: apparently there is part of me that remains indecipherable to the overlapping and all-encompassing systems of surveillance and control that define our present and our futures.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her book Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is editor of the forthcoming Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2019), and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.