Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Haunting, evocative paintings by a founder of LA’s Underground Museum.

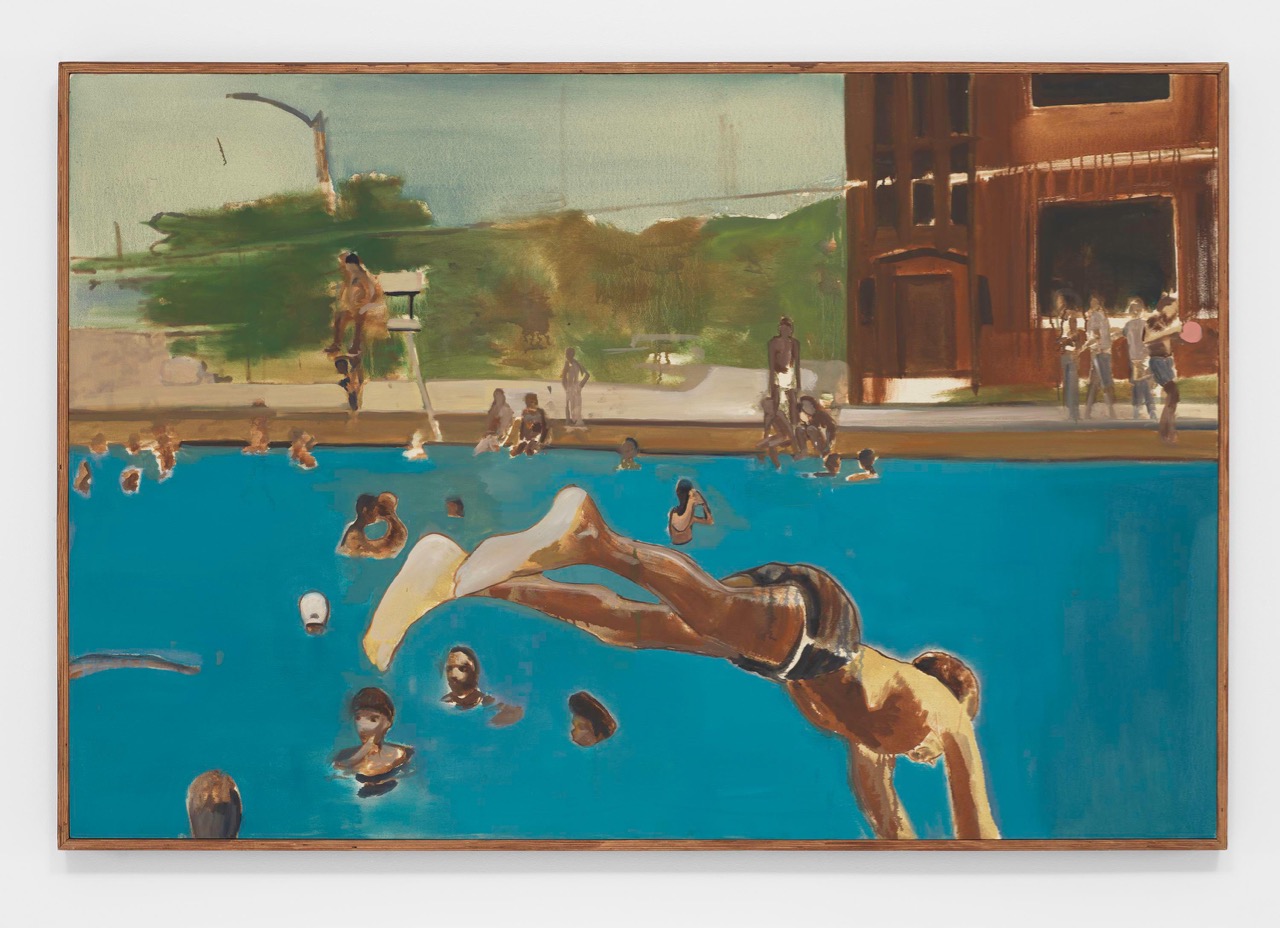

Noah Davis, 1975 (8), 2013. © Estate of Noah Davis. Image courtesy Estate of Noah Davis.

Noah Davis, David Zwirner, 525 and 533 West Nineteenth Street,

New York City, through February 22, 2020

• • •

By the time Los Angeles–based artist Noah Davis passed away in 2015, at the tragically early age of thirty-two, he had made a mark on two distinct fronts: first, as a figurative painter, and second, as the principal founder of the Underground Museum, one of the most interesting Black-centered art spaces to have emerged in the US in recent years. While Davis’s latter achievement is more widely known, a new exhibition at David Zwirner shines a light on the former: curated by Helen Molesworth, the show gathers thirty-one of the artist’s canvases made between 2007 and his death, demonstrating the depth of his talent and suggesting ways in which his approach to painting shared common ground with his vision for the museum.

Cofounded with his wife, the sculptor Karon Davis, and in collaboration with his brother, the filmmaker and video artist Kahlil Joseph, along with other friends and family members, the Underground Museum opened its doors in 2012 in three adjacent storefronts in Los Angeles’s Arlington Heights—a largely working-class Black and Latinx neighborhood. Over time, the project has become a vital center for the arts, as well as a community hub, entertainment venue, educational resource, and even salon—a place where visitors are as likely to attend Solange’s record launch as they are to take part in a yoga class or shop at an on-site farmers market or see an art exhibition that includes the likes of David Hammons, Pope.L, and Deana Lawson.

In contrast to many mainstream museums trying to bring “diverse” audiences to their doorsteps, Davis’s idea was the opposite, and all the more radical for it: he wanted to deliver “museum quality” art to an underserved area. Until he managed to convince established institutions to partner with him by lending works (an effort that eventually led to a relationship with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and then-MOCA curator Molesworth), Davis found clever and subversive ways to make do. His first show in the space, The Imitation of Wealth, recreated blue-chip artworks—a Jeff Koons vacuum cleaner, a Marcel Duchamp bottle dryer, a Dan Flavin fluorescent-light sculpture, and so on—using inexpensive stuff he sourced on Craigslist or in a hardware store, thereby “bringing a high-end gallery into a place that has no cultural outlets within walking distance,” as he explained in an interview. This détournement cannily challenged the terms of the élite art market—what, for example, makes a Koons Hoover at Gagosian Gallery more valuable or worthy of contemplation than a Davis Craigslist find in a storefront in Arlington Heights? But it did so, importantly, by claiming and putting to use an artistic canon that, for all its blind spots and exclusions, belonged to him and his neighbors as much as to anyone else.

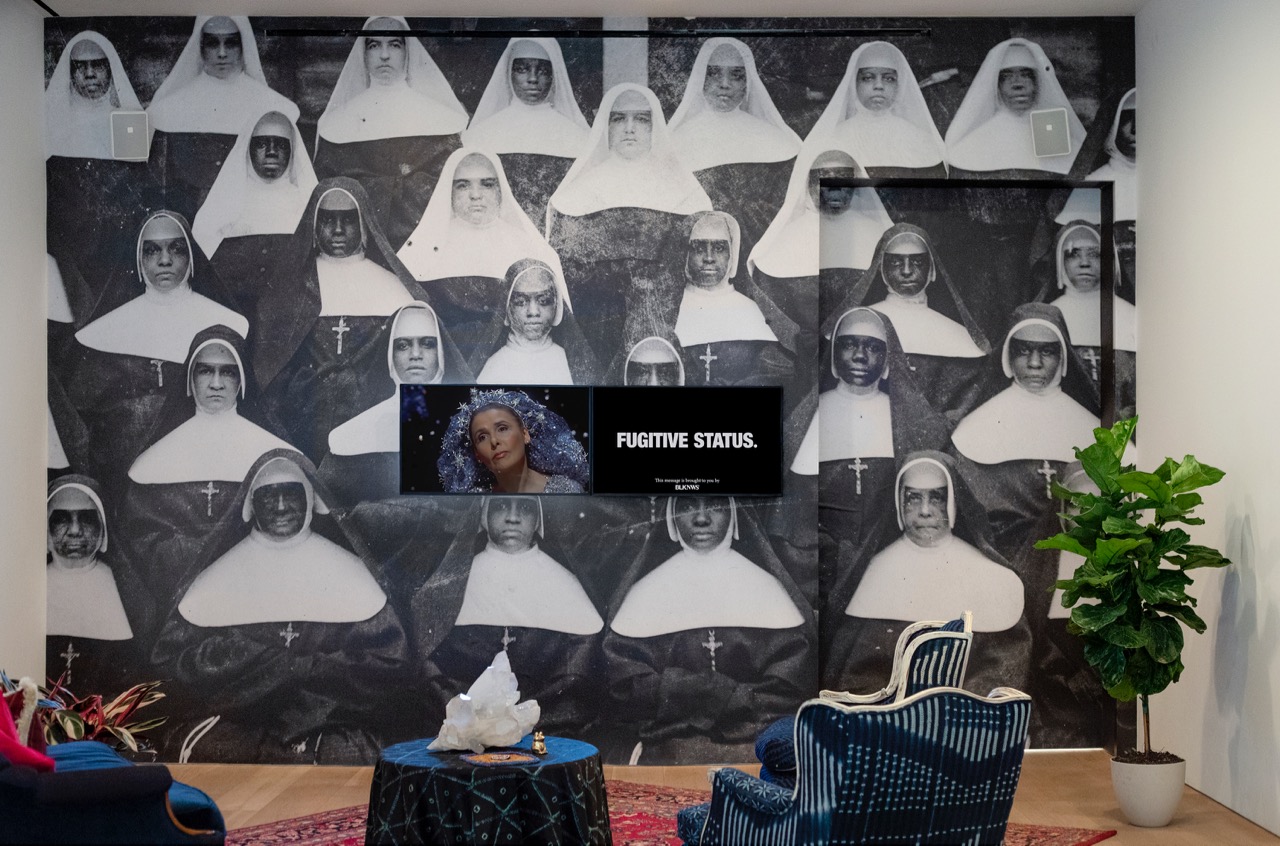

Noah Davis, installation view. Image courtesy Estate of Noah Davis and David Zwirner.

Tucked away in one of Zwirner’s side galleries is an installation meant to stand in for the back offices of the Underground Museum: art by Noah Davis, Karon Davis, and Joseph; Shelby George furniture designed by Davis and Joseph’s mother, Faith Childs-Davis; models for past exhibitions; and a selection of books from Zwirner’s library give a sense of the informal, familial, and generous nature of the venture. Seeing the radical institution reabsorbed by the very type of high-end gallery it was meant to challenge and subvert is disconcerting, no matter how valuable the gesture is for contextualizing Davis’s studio practice. Happily, though, the real focus of the show is the artist’s paintings, which occupy the rest of the gallery’s massive Chelsea outpost. This work—muted but lush, haunting, deeply evocative—loses none of its potency in its relocation to Zwirner.

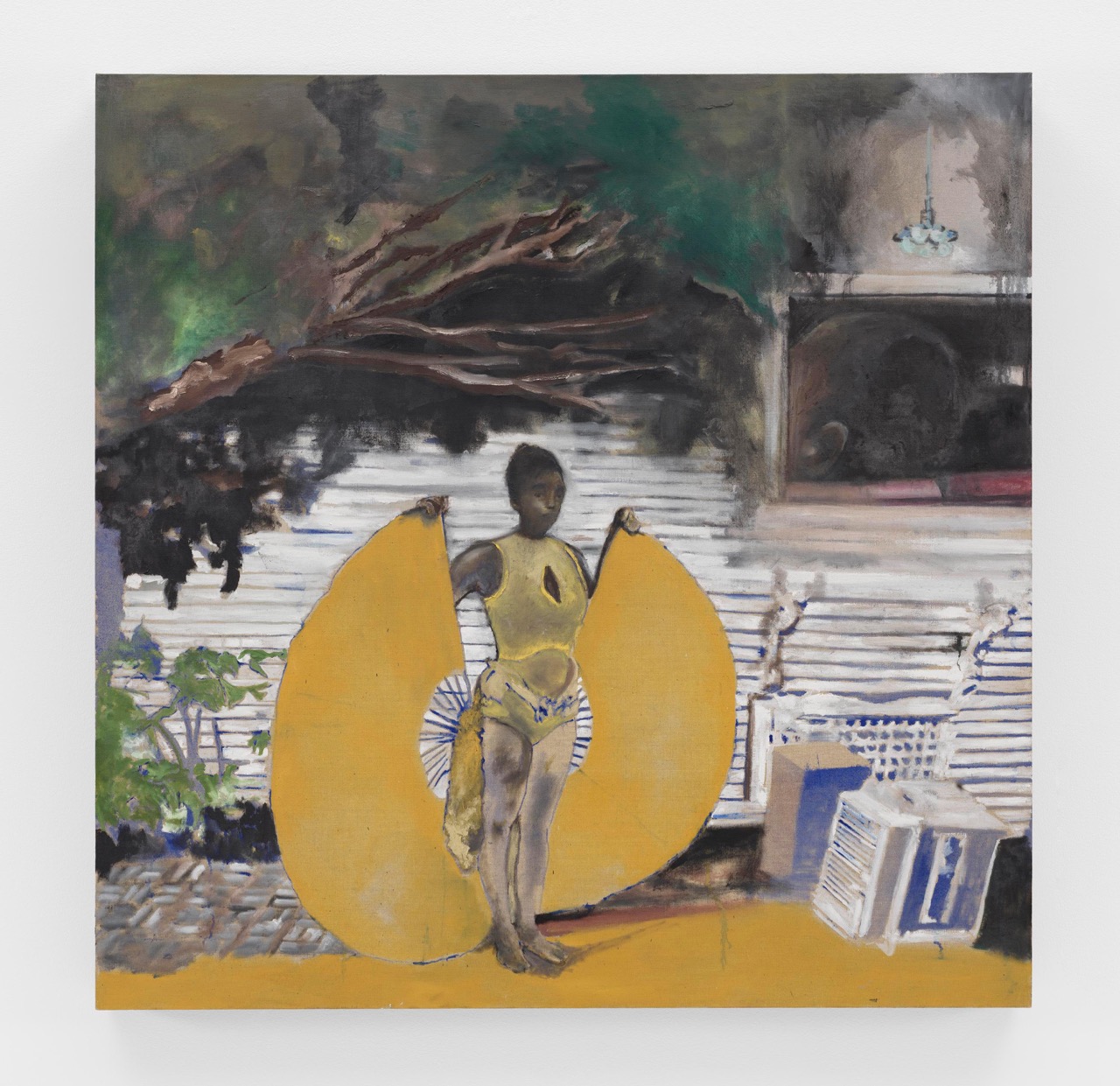

Noah Davis, Isis, 2009. © Estate of Noah Davis. Image courtesy Estate of Noah Davis.

Though distinct from the Underground Museum, Davis’s poetic, atmospheric paintings share with that project an abiding museological impulse in their desire to engage the history of art to tell resonant stories about Black subjects. Isis (2009), done in oil and acrylic on a forty-eight-inch-square support, depicts a leotard-clad woman with a melancholy gaze in a contradictory space. At first glance, she looks to be standing against the exterior of a clapboard house, alongside a discarded box and an air-conditioning unit and shaded by some tree branches, but, thanks to a patch of parquet flooring, it might equally be a stage set. And what is she doing there at any rate, holding up a goldenrod-hued, circular, fanlike—train? skirt? wings? parachute? And why is the interior of this modest house adorned with a glittering chandelier, visible through a large window in the upper right? Yet for all this indeterminacy, the picture is firmly rooted in art history: that chandelier is lifted from Édouard Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère, the scrubby application of paint to stand for foliage evokes passages from Edgar Degas’s depictions of ballet and theatrical sets, and the woman herself seems to be a time-traveling version of Miss La La, a Black acrobat depicted by Degas and other French artists in her heyday performing in the cabaret halls of Paris.

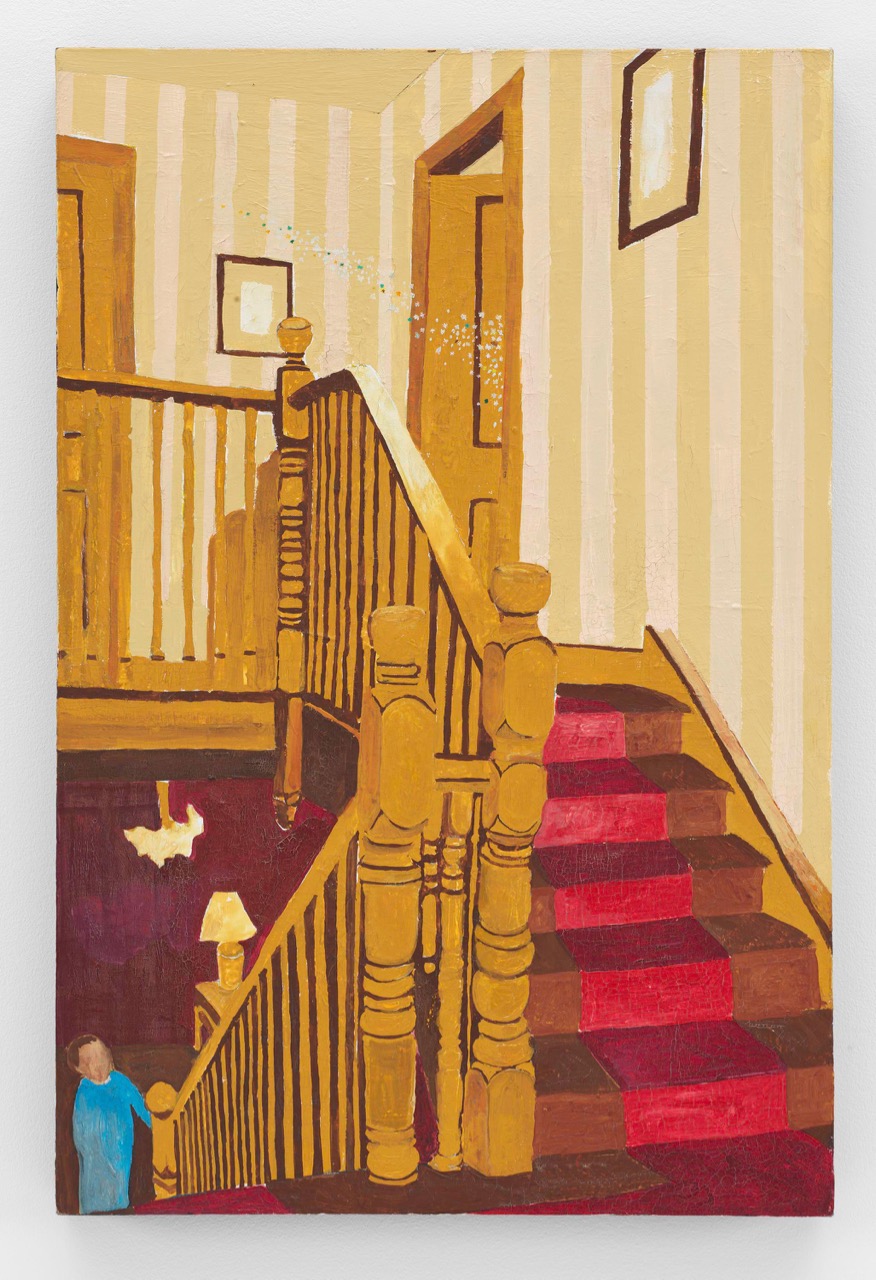

Noah Davis, Delusions of Grandeur, 2007. © Estate of Noah Davis. Image courtesy Estate of Noah Davis.

Delusions of Grandeur (2007), a vertical canvas rendered in oil and gouache, is a jewel-like scene of intimate domesticity straight out of Édouard Vuillard and the Nabis: tucked in the lower left-hand corner of the composition, a small, faceless child clad in cerulean blue contemplates climbing a flight of stairs. The repetition of verticals—the yellow-striped wallpaper, the mustard-colored balustrades and newels, the red runner that snakes up the steps, the door frames on the second floor, the empty picture frames that hang on the wall—suggest the Herculean nature of the task from the child’s point of view, resulting in a deft psychological portrait. The visage of the Black Boy Scout (2013) is impastoed and scumbled, like Paul Cézanne’s early portraits of his Uncle Dominique; the foreground figure in 1975 (8) (2013) dives into the azure expanse of a David Hockney swimming pool; two abandoned Edward Hopper houses float against a Mark Rothko–like background in The “Fitz” (2015). Such historical references provide much-needed ballast for work that can be almost disorienting in its emotional intensity.

Noah Davis, Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque, 2014. © Estate of Noah Davis. Image courtesy Estate of Noah Davis.

A strong cinematic mood is apparent in two paintings drawn from a 2014 series depicting Pueblo del Rio. One of LA’s oldest and largest housing projects, designed by modernist architects including Richard Neutra and Paul Revere Williams in the early 1940s, it was eventually plagued by poverty, gang violence, and over-policing. Davis’s paintings function as an imaginative reclamation of space, in which Black artists (a classical pianist playing a concert grand in Pueblo del Rio: Concerto, ballerinas in a strict, symmetrical formation in Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque) reanimate empty architecture with their creative endeavors—not a bad analogue for what Davis and his collaborators were building in three dimensions.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, an upcoming retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a member of the advisory board of 4Columns. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.