Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In a new exhibition of the artist’s work, a refusal to be defined by conventional borders and colonial histories.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum: I have withheld much more than I have written, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum: I have withheld much more than I have written, Galerie Lelong & Co., 528 West Twenty-Sixth Street, New York City, through October 22, 2022

• • •

The title of Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s first solo show in New York City, I have withheld much more than I have written, comes from a 2018 cycle of prose poems by Dionne Brand, The Blue Clerk. In it, we hear of a writer whose verso pages of her notebook—those left blank—are being carefully baled and cataloged, becoming a burdensome archive of the unsaid. The installation and nine paintings on view at Galerie Lelong (all 2022) are dense with citations from literature, art history, geology, ethnography, landscape painting, music, film, and theater, and are composed of intricate layers of marks and images. Sunstrum’s borrowing from Brand is curious, for what could possibly be left out of this thicket of meaning? The move suggests that in the artist’s quest to address how the subject is formed within families, in diasporic movements, and in relation to colonial histories, even this surfeit of references is not sufficient to convey the complexity of experience.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum: I have withheld much more than I have written, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum. Pictured: Mumbo Jumbo and the Committee, 2022. Installation with wood, film, and painting components; running time: 56 seconds; painting: 48 1/8 × 96 inches.

The show opens with Mumbo Jumbo and the Committee, which has three main components: a stop-motion film projected onto a wood-framed screen standing near one wall; a set of uncomfortable, straight-backed wooden pews in the middle of the room; and, on the opposite wall, a wood panel diptych with oil and pencil (The Committee) portraying an audience of dark-skinned Victorian men and women sitting in a drawing room around and behind a red projector. Standing in front of the painting, you are caught up in their gazes, which hover between curious appraisal and strict disapproval. Turn around, sit on the pews, and you become part of this surveilling ensemble, looking at what they see through that red projector: Sunstrum’s film, featuring seven characters, all played by the artist, wearing different nineteenth century–esque costumes that communicate subtle, yet unmistakable, variations of class and station. A colonial adventuress fusses over a recording device while others lounge, receive, and attend. They occupy an interior with a checkerboard floor, chairs and settees of different styles and periods (including very contemporary), a flimsy portable movie screen, and other props and décor. Strangely, the back wall of this room is not at all wall-like: it opens out onto or dissolves into a landscape painting, complete with a smoldering volcano, that nods both to Frederic Edwin Church’s spectacular 1862 images of the Cotopaxi volcano in the Ecuadorian Andes and to Daguerre’s diorama theaters, in which audiences were regaled for the first time with a moving image animated by sound and light effects, a precursor of modern cinema.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum: I have withheld much more than I have written, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum. Pictured: Mumbo Jumbo and the Committee, 2022. Installation with wood, film, and painting components; running time: 56 seconds.

In this scene, Sunstrum, via her alter egos, becomes entangled in many of the discourses and technologies that exert pressure on Black women’s identities: the colonial penchant for measurement and categorization; the ethnographic applications of painting, drawing, photography, and film; the relationship of “the native” to the land; and the spectacularization of the female body among them. But there is another set of terms at play here, having to do not with the extrinsic demands and limitations imposed by whiteness but with the intrinsic expectations of family and community—that disapproving Committee is, like the artist herself, Black. As ever, the title is a signal: the term “mumbo jumbo” descends from a Mandinka word that was introduced into English by a British colonist and has come to mean, in a derisive way, a deliberately confusing language. In its original context, it may have referred to a masked male dancer who would resolve conflicts within polygamous households, usually by punishing women for stepping out of line. The word seems to perfectly sum up the double bind that the piece alludes to.

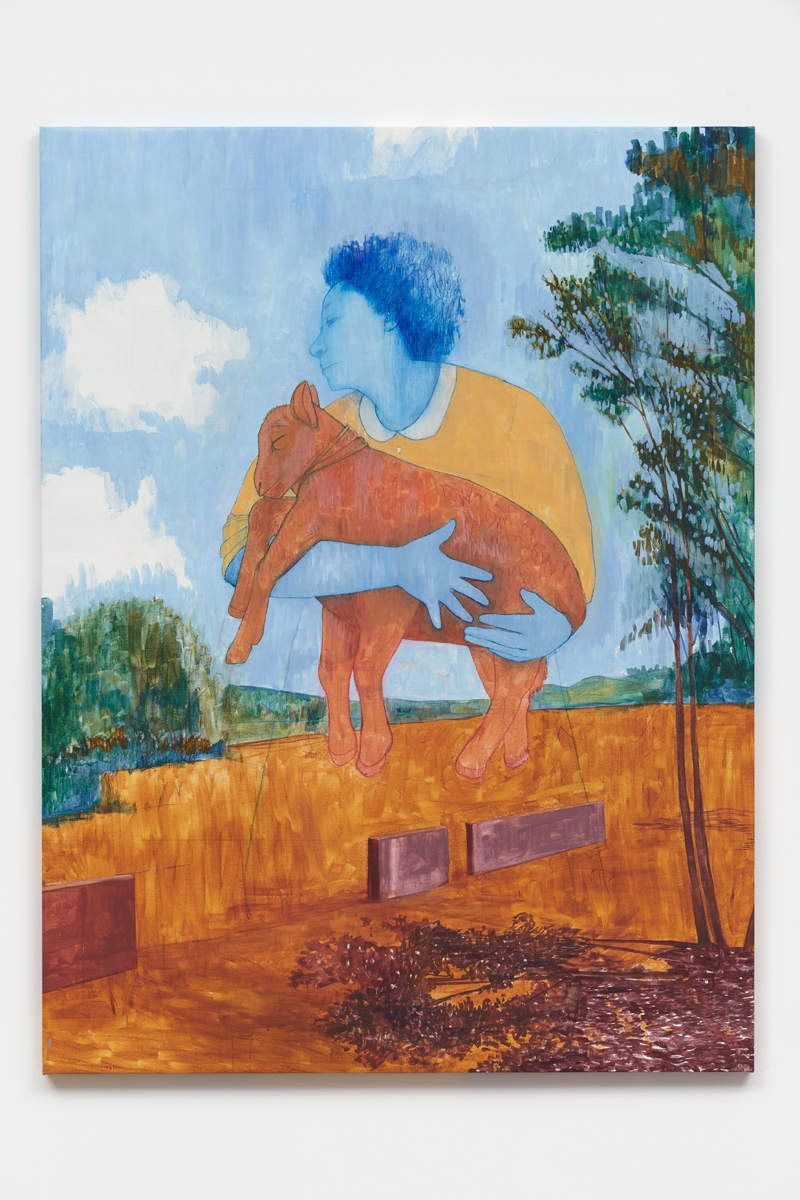

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Lambsheart, 2022. Oil and pencil on linen, 78 3/4 × 66 7/8 inches. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum.

Sunstrum was born in Botswana to a Botswanan mother and a (white) Canadian father and has lived in various parts of Africa, Southeast Asia, Canada, and the US; in her adulthood, she has been forced to move because of immigration rules that categorized her as not sufficiently one thing or another. She has described feeling as a child like she and her nomadic family were “a traveling band of a spectacle,” a familiar experience for those whose identities span borders and taxonomies of racialization.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Frangipani, 2022. Oil and pencil on linen, 78 3/4 × 66 7/8 inches. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum.

This theme of belonging and unbelonging that marks diasporic experience weaves its way through the paintings in the main gallery. Lambsheart portrays a blue-skinned woman cradling a six-legged baby sheep in her arms. The figure (a stand-in for the artist, as in most of the works here) has no belly or legs, but hovers, unrooted, above the yard of her grandmother’s house in Botswana. You can see the remnants of a crumbling, temporary outbuilding below, one of many successively built on this spot as per local custom, a palimpsest of the way the land was used over time. In Frangipani, a woman finds solace from the harsh southern African sun under the branches of a shade tree, the dapples of sunlight and shadows of leaves on her dress tying her to the landscape while her blue-shod feet—four of them—suggest movement, even flight, as if she were a stilled Muybridge photograph. Based on the French artist Auguste Toulmouche’s academic painting The Hesitant Fiancée (1866), Front Room depicts a woman seated in an armchair, her hands clasped by two others who bend over or crouch beside her. A third gazes out an open doorway, either standing guard or yearning for freedom, it’s hard to tell. It is unclear, too, whether the embraces we see are comforting and supportive or repressive and restrictive, though, truth be told, in real families it’s often hard to parse that distinction anyway.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Front Room, 2022. Oil and pencil on linen, 78 3/4 × 86 5/8 inches. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum.

In a video on the gallery’s website, Sunstrum says that she often refers to her work as drawing, even when it moves into the space of painting. And indeed, the artist mines the history and formal opportunities of her favored medium to reinforce her understanding of identity as a sedimentation of the myriad ways power manifests, from the grandest of longue-durée histories to the microcosmic interactions within families. Sinner Get Ready is a gorgeous example: across two joined-wood panels, you see a checkered floor (echoing the setting of Mumbo Jumbo and the Committee) and settee rendered in colored pencil and thin washes of oil; ghostly layers of a landscape (this one borrowed from a nineteenth-century Black artist, Robert S. Duncanson); and palm trees as well as other, less-definable objects. In one of the multiple foreground planes that make up this image a woman lies prone with legs bent in the air—those tender toes! that limpid hand!—and a visage so oversize that it reads as a moai statue from Easter Island. The drawing is precise, even classical, in a way that recalls both the best of nineteenth-century high art and the other, more prosaic uses to which drawing was put at the time, including the recording of colonial territories and people.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Sinner Get Ready, 2022. Oil and pencil on wood panels, 40 1/8 × 63 3/4 inches. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum.

The woman in Sinner Get Ready is captured by such an ethnographic pencil, but defies it, too, with her fierce countenance. Whatever we might think we know about her, whatever her overdetermination by the discourses that produce her in our imaginations, she exceeds what the line can describe, or what words can say. Sunstrum’s brilliant hunger to put everything in her images reveals the language that tries to bind Black womanhood as so much mumbo jumbo, and offers up a space for imagining differently.

Aruna D’Souza is the 2022–23 W. W. Corcoran Professor of Social Engagement at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, DC and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.