Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In the work of six Black artists, representation beyond

white supremacy’s archives.

The Black Index, installation view. Courtesy Leubsdorf Gallery. Photo: Stan Narten. Pictured: Alicia Henry, Analogous III, 2020.

The Black Index, curated by Bridget R. Cooks, Bertha and Karl Leubsdorf Gallery at Hunter College, 132 East Sixty-Eighth Street,

through April 3, 2022

• • •

Quick on the heels of the invention of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, criminologists, sociologists, and ethnographers seized upon the new technology to facilitate their mission to explain the world by indexing it. Through a process of categorization, people—colonial subjects, the lower classes, deviants of all kinds, but, above all, Black-skinned people—were reduced to types, imprisoned within discourses of criminality, disposability, death, and abjectness that were all but impossible to exceed. This curtailment of Black subjectivity was achieved, in part, by the sheer repetition that photography allows, a repetition that is numbingly apparent in the American visual landscape, in the hundreds of photos of Black bodies hanging from trees that haunt our archives, in the infuriatingly endless images of people rendered lifeless by police violence, in the one-after-another monotony of mugshots. Any one of these pictures (or the events they represent) may serve to strip the humanity of an individual, but the appearance of hundreds and then thousands and then millions of them over time strip the humanity of a people as a whole.

The Black Index, installation view. Courtesy Leubsdorf Gallery. Photo: Stan Narten.

“The Black Index,” a term coined by Dr. Bridget Cooks, a scholar of African American Studies and Art History at University of California, Irvine, serves as the conceptual motor for a show she has curated that is now at the Leubsdorf Gallery at Hunter College. If the index—or, to supply the almost always missing term, the white index—is a way of recording, organizing, and retrieving knowledge, the Black Index, as sketched out by the six artists included in this small but exceedingly thoughtful exhibition, is an anti-archival project, resisting the ways that such work of categorization, visual and otherwise, have long been part of a larger system of antiblackness. In semiotic terms, the index is a sign that claims an essential, physical link to what it represents: just as smoke is a sign for fire, a photograph is a chemical imprint of light playing off the sitter. Photography, in other words, is evidentiary, and the white index draws upon that presumption of truth. The works gathered in Cooks’s show explore, by turns, the way that photography, despite its claims, constructs its own falsehoods, and in so doing demonstrates what is left out of its purview.

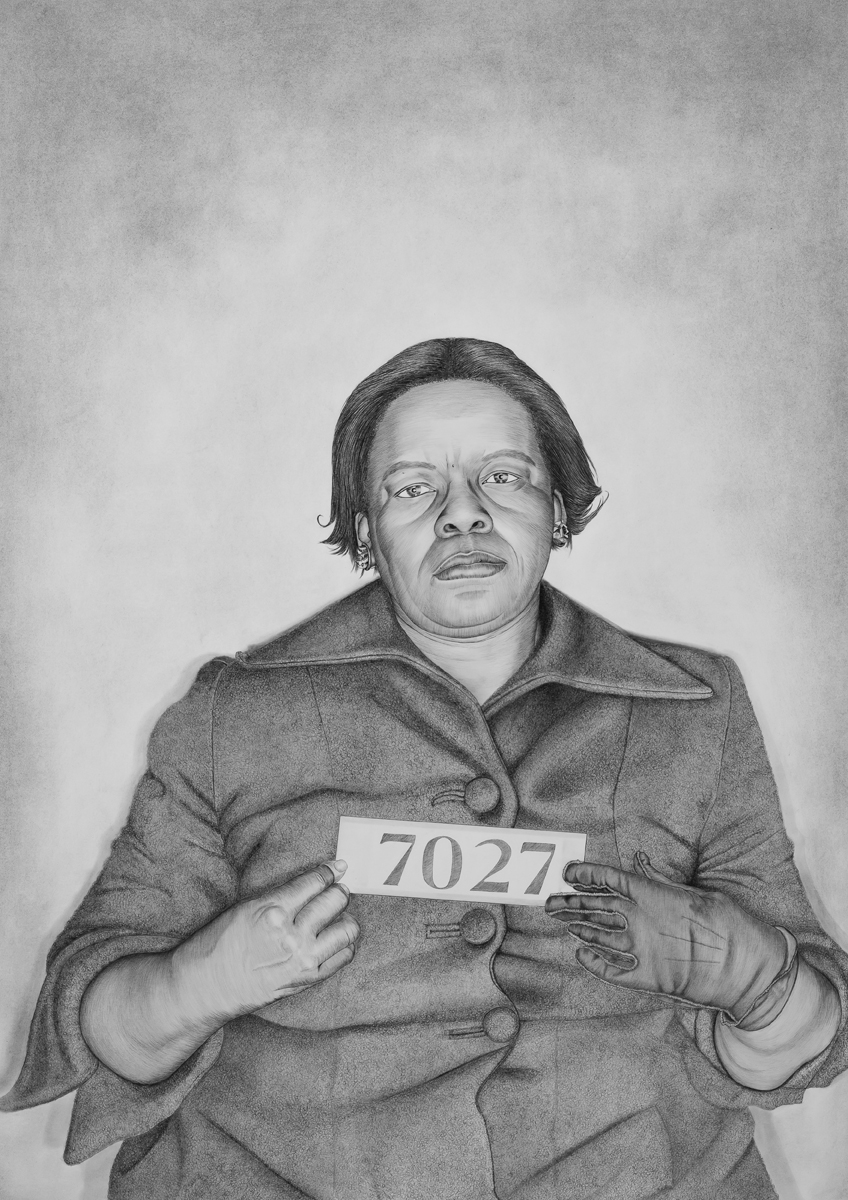

Lava Thomas, Mugshot Portraits: Women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Alberta J. James, 2018. Graphite and conté pencil on paper, 47 × 33 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery. Photo: Phillip Maisel.

Enter from the street side of the gallery and the first works you will see are three drawings from Lava Thomas’s Mugshot Portraits: Women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. (Though the series is ongoing, the three pictures here were all made in 2018.) Based on police photos of women arrested during the Alabama protests, Thomas’s precise, mimetic renderings in graphite and conté pencil entirely upend the visual conventions of the arrest photo: where mugshots attempt to reduce the sitter to a booking number and the status of a criminal, Jo Ann Robinson, Alberta J. James, and Addie J. Hamerter are instead revealed in their insistent individuality.

The Black Index, installation view. Courtesy Leubsdorf Gallery. Photo: Stan Narten. Pictured: Whitfield Lovell, The Card Pieces, 2020.

An earring, the knit of a sweater, one leather glove (the other presumably lost in the demonstration), a hint of a defiant smile: by homing in on these tiny details in the source images, Thomas restores some of the dignity the police tried to strip away from these protesters. The same strategy—using slow, careful, and loving attention to make space for the Black subject—animates Whitfield Lovell’s The Card Pieces (2020). In each of the twenty-four works, the artist pairs a charcoal pencil drawing, based on a photograph, with a real playing card that is collaged below. Some of Lovell’s sources come from family albums, old tintypes, photo-booth pictures, and the like. In contrast to the frightful images of Black pain that litter our social media feeds, these are pictures taken to commemorate, to celebrate, to record moments of pleasure, or even love. (The full series, which is still in process, will include one drawing for each of the fifty-four cards, including the jokers, in the vintage deck.) The juxtaposition of figure and playing card is not necessarily arbitrary: a drawing of Lovell’s mother, the only identifiable person in the group, hovers above the ace of hearts, a seemingly deliberate choice. But in most cases, the relationship is not obviously meaningful. It is mysterious enough, that is, to open up a space of imagination. We are encouraged to wonder about the life, the personality, the events that might have made it appropriate to pair this elderly woman with a king of spades or that young man with a five of diamonds, and so on. What might have been a parlor game now becomes a challenge to us to attribute a subjective fulsomeness to people who might have otherwise gone unnoticed—that is, to surmise the hand that fate may have dealt them.

The Black Index, installation view. Courtesy Leubsdorf Gallery. Photo: Stan Narten. Pictured: Alicia Henry, Analogous III (detail), 2020.

As much as individuality is insisted upon, so is collectivity. The Civil Rights protesters depicted by Thomas, for example, found their strength in numbers. In a canny curatorial move, next to her drawings is a piece, both tender and eerie, by Tennessee-based artist Alicia Henry. Analogous III (2020) is made up of three hundred or so faces, fashioned from leather, sometimes embellished with thread and paint. They are assorted sizes and shapes, and the leather is treated in different ways (dyed, soaked, air-dried), producing varied tonalities and causing them to curl and buckle irregularly. Eyes and noses and mouths are cut out crudely, yet carefully, so that the faces seem both masklike (in other words, obscuring identity) and decidedly particular. The cutouts are grouped on the wall in a manner that suggests movement—like a parade, or a procession (perhaps a funeral procession?), or a march.

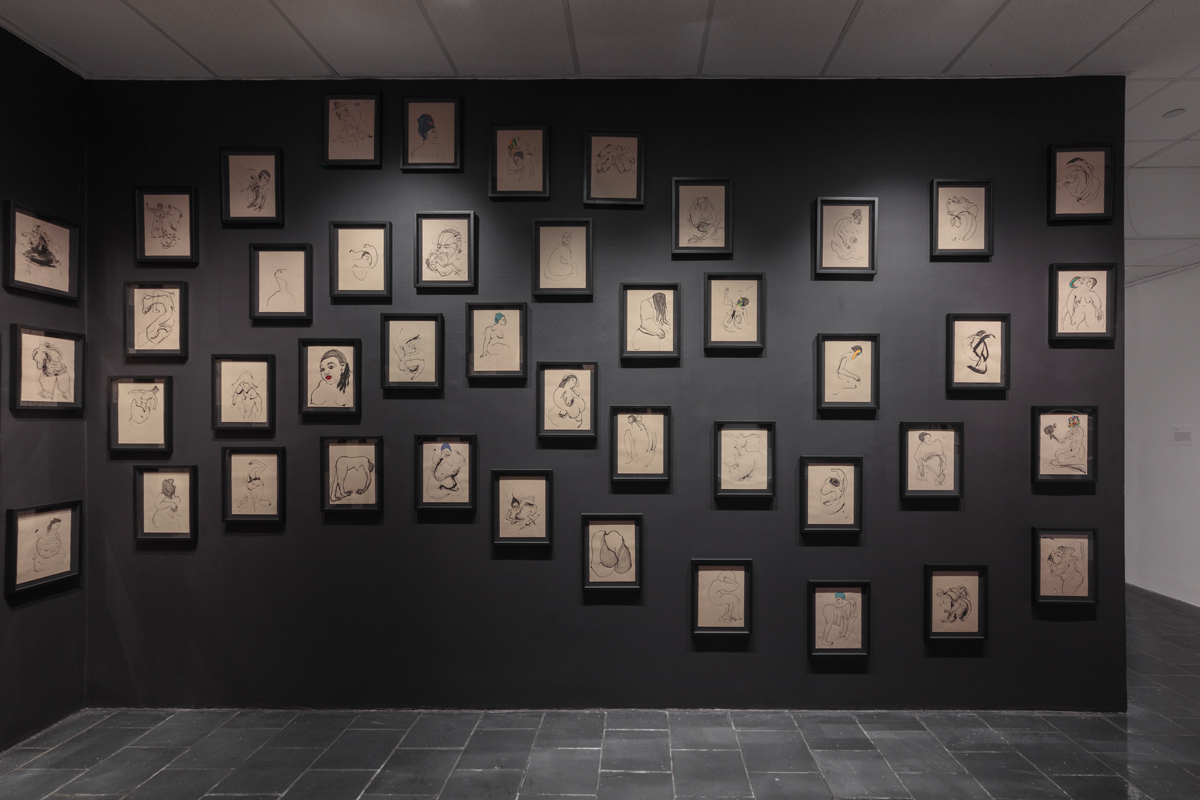

The Black Index, installation view. Courtesy Leubsdorf Gallery. Photo: Stan Narten. Pictured: Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, The Evanesced: The Untouchables, 2020.

The care that emanates from Henry’s approach—a care that is as much about the sensitive treatment of her materials as it is about the abstracted figures she’s depicting—is also evident in one of the most stunning pieces in the show, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle’s The Evanesced: The Untouchables (2020), a hundred India ink and watercolor drawings of women. The series grows out of a larger body of work Hinkle has been making since 2016 in honor of the countless number of Black women who have been murdered, trafficked, abused, or disappeared around the world. The Untouchables adds to this community of lost souls those who have died in the COVID epidemic. The artist refers to the pictures as unportraits—stand-ins for, perhaps, or representatives of a larger community of women whose lives were treated as disposable. Decidedly nonmimetic in form, Hinkle’s drawings function as homages, but also as conduits for the power, energy, and vitality of the lives that were lost. Some of her subjects have two heads, others seem to drip eyes from their full breasts, still others float or fly or smile or mourn. The artist renders the lines quickly, using brushes she makes herself—the ritual of crafting her tools is part of the way she pays tribute to her subjects—and, because they are in ink, once they are put down on paper they are fixed. In a world that wants to efface Black women, Hinkle’s work seems to brook no possibility of erasure. The Evanesced creates a kind of counter-index: while organized by an overarching category (women who have been murdered, abused, etc.), its subjects resist categorization. Like the other artists in this exhibition, Hinkle offers up Black life, acknowledging but defiantly resisting white supremacy’s archives of Black pain, violence, and death.

Aruna D’Souza is currently Edmond J. Safra Visiting Professor at the National Gallery of Art and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. A forthcoming collection of the writings of Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames & Hudson), which she edited, will be released in March 2022. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.