Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The exhibition Black Vessel examines the artist’s object-oriented work.

Theaster Gates, Vessel #19, 2020. High-fired stoneware with glaze, 19 × 20 × 20 inches. © Theaster Gates. Photo: Chris Strong. Courtesy Gagosian.

Theaster Gates: Black Vessel, Gagosian, 555 West Twenty-Fourth Street, New York City, through December 19, 2020

• • •

Theaster Gates’s new show at Gagosian is full of intriguing objects—endlessly varied ceramics, Arte Povera–esque paintings made out of roofing materials, and large sculptural installations. This is itself notable, because he’s someone best known not so much for making things as for leveraging his position as an artist to intervene in the world, creating new opportunities for social encounter, community, and collaboration. His most ambitious undertaking, Rebuild Foundation, established in the early 2010s, emerged from Gates’s efforts to buy up and restore buildings on the South Side of Chicago. Along with a growing team of collaborators and employees, the artist hired and trained residents to assist with the work of renovation and rehabilitation; so celebrated was his approach to neighborhood revitalization by powerful Chicagoans that the city agreed to sell him the abandoned Stony Island Trust and Savings Bank building for one dollar to further his efforts. Gates and his team transformed the site into a cultural hub and exhibition space.

Depending on whom you talk to, Gates is either a visionary or—as he has identified himself in the past (though probably more to lean in to criticism than to claim the term)—a hustler: someone who has done much to reinvest in the people and resources of areas left to wither as a result of the intersecting logics of capitalism and white supremacy, or someone who has cynically exploited those same logics, aligned himself with shady politicians like Rahm Emanuel, and taken advantage of white liberal racism in order to create a showcase for his own artistic ambitions.

Theaster Gates’s ceramics studio, Chicago, 2020. © Theaster Gates. Photo: Chris Strong. Courtesy Gagosian.

The truth lies somewhere in between these two pictures: Gates is a complicated mix of opportunism and sincerity. It’s this latter quality that seems to be on full display in Black Vessel, which traces the origins of Gates’s recent object-oriented work. The show argues that whether working in the realm of social practice, ceramics, painting, or installation, the artist has long been thinking in terms of recognizing the value of Black labor and creativity, protecting Black cultural legacies, and transforming spaces to accommodate new loci for Black spiritual experience. The title of the exhibition refers to Gates’s embrace of the vessel as a conceptual motor for the entirety of his oeuvre; he states in the press release that “I always find myself returning to the vessel. It is part of the intellectual life force of my practice and it precedes all other forms of making.”

Theaster Gates: Black Vessel, 2020, installation view. Artwork © Theaster Gates. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

This through line in Gates’s thinking is most clearly visible in the third of four galleries, where twenty-six ceramic sculptures are installed on rough wooden pedestals of different heights and occasionally on the floor; the viewer is invited to walk between and around the pieces to examine them from every angle. Titled Vessels (2019–20), the arrangement speaks on several levels: art historically, it evokes the jumble of modernist sculptor Constantin Brancusi’s studio, while metaphorically it reminds one of being among a group of people. (Each of the sculptures is decidedly individual and distinct, ranging from open pots to bristled spheres to kettlebell-shaped weights to biomorphic humanoid forms, with different glazes and finishes and allusions to Western, Eastern, and African aesthetic models.) In a video accompanying the show—there is no catalog, but Gagosian’s seemingly endless resources have been put toward an extensive interpretive apparatus, including the video and articles in the gallery’s eponymous magazine—Gates speaks about his pottery studio as itself a kind of vessel where people congregate to help him fire his creations, as a space of sociability. Vessels recreates that same atmosphere in the gallery.

Theaster Gates: Black Vessel, 2020, installation view. Artwork © Theaster Gates. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

In the next, massive, room, Gates invokes the vessel once again: by lining the walls of the space with handmade, glossy black bricks, the artist blurs the lines between sculpture and architecture. He also—as with his monumental and aesthetically satisfying paintings fashioned from roofing material, a nod both to his father’s trade and to the work that goes into neighborhood revitalization—blurs the line between art, craft, and commerce: his ceramic blocks are made from crushed-up brick remnants from a commercial manufacturer in North Carolina with which he has partnered. He refashions the bits and pieces and then fires the new forms at extremely high temperatures.

Theaster Gates: Black Vessel, 2020, installation view. Artwork © Theaster Gates. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

In the brick-lined gallery, we find three sculptures, two of which explore another abiding theme in Gates’s work: that of creating and preserving archives of Black knowledge. (One of the primary functions of the Stony Island Arts Bank is to serve as an open-access library and cultural repository.) The first of these objects, New Egypt Sanctuary of the Holy Word and Image (2017), is a tall wooden structure lined with books. From the outside, one cannot see their spines. Only by stepping through a narrow opening onto an elaborately tiled floor—a fragment of the altar salvaged from the since-demolished St. Laurence Church in Chicago—can one identify the tomes as bound volumes of Ebony. Some 15,000 copies of the magazine were destined for the trash when the Black-owned Johnson Publishing Company shut down in 2016, until its president donated them all to Gates at his request. The artist counters the aspirational, middle-class point of view contained in Ebony by encasing the magazines in bindings that are red, black, and green—the colors of the Black Power Movement.

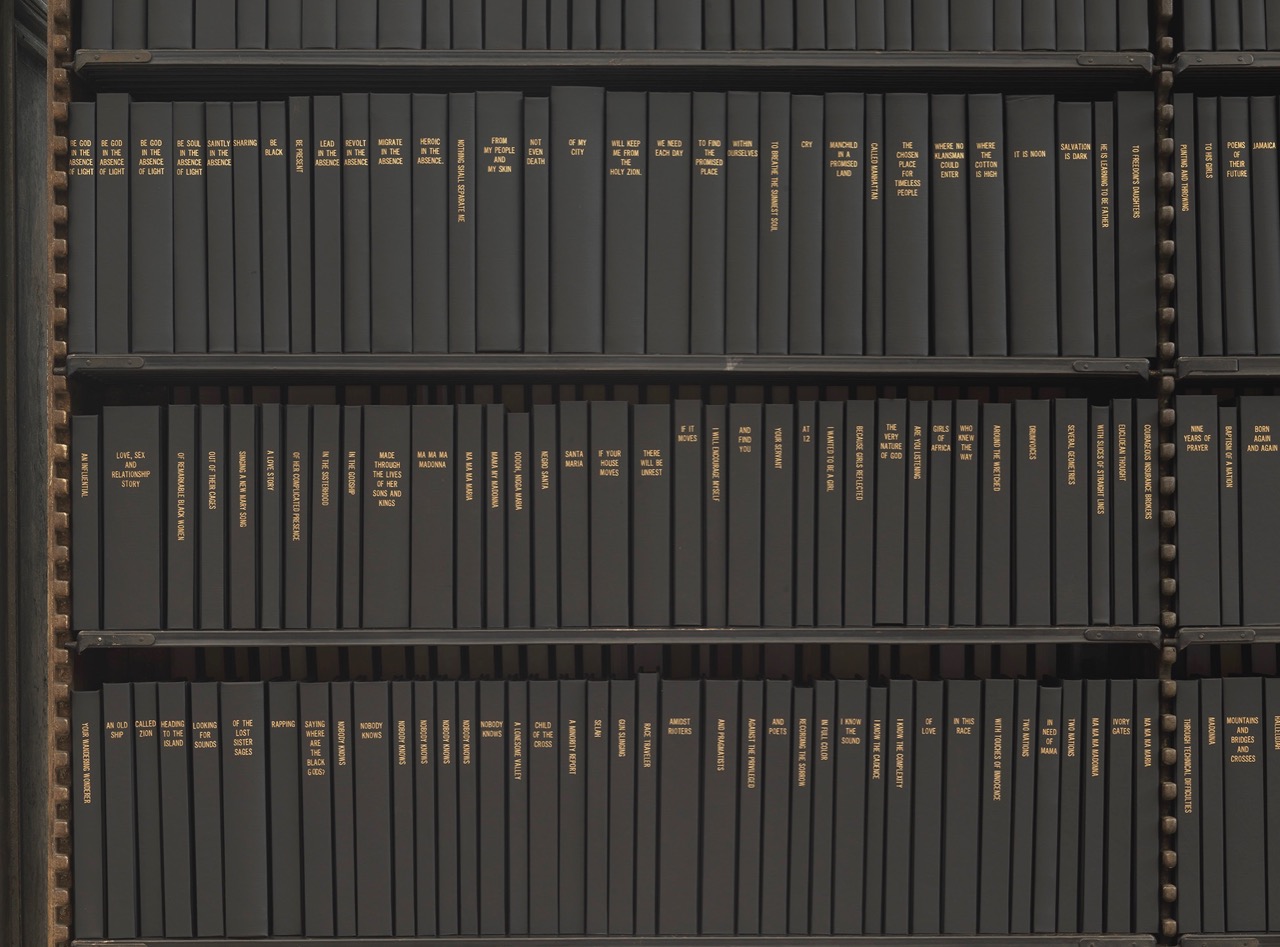

Theaster Gates, Walking Prayer, 2018–20. Bound embossed books and vintage Carnegie cast-iron shelving, 83 × 320 × 19 inches. © Theaster Gates. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

The second object in this room is Walking Prayer (2018–20), another book-related work. Here, we find a salvaged cast-iron library shelving unit, one of the innovations introduced when Andrew Carnegie undertook his early twentieth-century democracy-building project of creating free libraries around the United States and the world. It contains 2,400 identically black-bound books with gold printing on their spines. While the wall label indicates that the contents of these volumes are writings on Black experience by different authors written at different times, their titles have been replaced with phrases of Gates’s own making. As you process down the length of the shelves, these phrases coalesce, sometimes clearly and sometimes not so, into a kind of poem, full of shifts and non sequiturs: “In My Dreams / Don’t Change / Remain the Loyal / Colored Girl / I’ve Always Known / Holy, in Deed / Holy, in Color / Holy, Among Your Brothers and Sisters / Holy, Holy, La Toya / Holy Torkwase / Holy is Your Name / Holy is Our Love” reads one section; “It is Time for a New Order / And Lord Knows I Hope to See It / A Dissociative Identity Disorder / A White Lie / A Black Power / A Black Labor / A Wealth of Possibility / Break Chains” reads another.

Theaster Gates, Walking Prayer, 2018–20, detail. Bound embossed books and vintage Carnegie cast-iron shelving, 83 × 320 × 19 inches. © Theaster Gates. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

The seductive power of works like this is thrown into doubt by the third piece in the room, at least for me—thrown into doubt in the sense that I start to wonder how much of their appeal is predicated on my naivete, or worse, on my inability to see through Gates’s predilection for leveraging liberal anti-Blackness. It consists of a Leslie speaker through which you hear a single chord played on a Hammond B3 organ, an instrument historically linked to Black churches. The sound adds an eerie, mournful, but also decidedly holy atmosphere to the cavernous space; per the artist, it is meant to point to the spiritual dimension of his practice as a whole, something he talks about extensively, including in an interview with Louise Neri in Gagosian’s magazine. In it, he goes so far as to wonder about the possibility of converting “a place of commerce into a sacred space.”

The question may be an intriguing one in relation to Stony Island Arts Bank, which he transformed from a capitalist institution into a site where Black culture is safeguarded and valued. But at one of the richest private art galleries in the world, an epicenter of art speculation and massive wealth hoarding, it sounds like a read: Are we supposed to imagine that Gagosian can transcend its venality under the pressure of Black spirituality? Or is he turning non-Black viewers like me into mindless consumers of Black culture, not that far different from the hordes of gawkers that take bus tours to Harlem to lay their eyes on Black gospel choirs at Sunday morning services before repairing to Sylvia’s for some chicken and waffles, and in doing so, believe they’ve gained an insight into the Black experience? There are moments when I feel like the brilliance of Gates—as an artist, as an impresario, as an activist—is that one never knows. And facing that ambiguity forces a kind of self-reflection that is both necessary and almost unbearably uncomfortable.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, an upcoming retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady’s Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a member of the advisory board of 4Columns. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.