Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The artist questions Pakistan’s legacies of colonialism and neoliberal economics via an imagined travel agency.

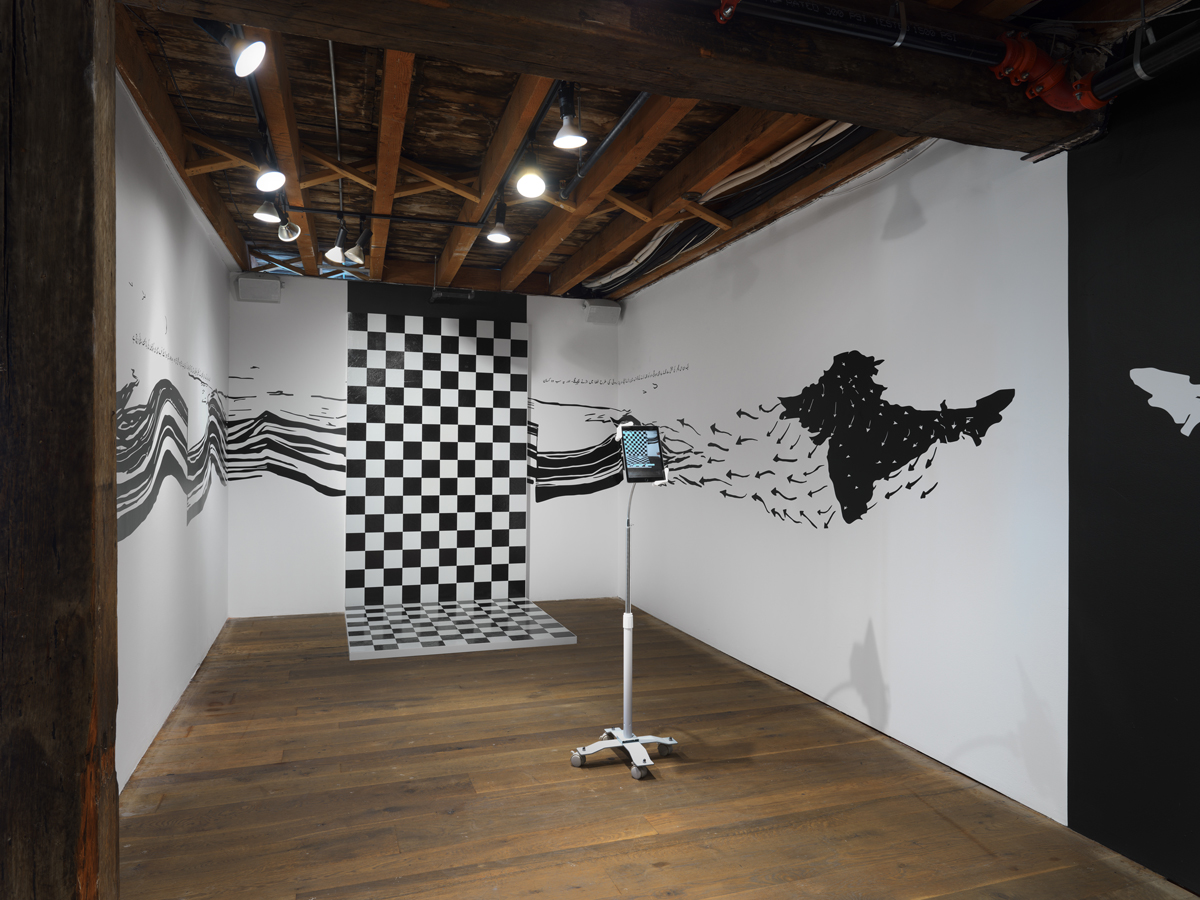

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Black mai chaiye, yah white mai? (Do you want it in black or white?), 2022. Wood, plaster, vinyl tiles, Unity AR software.

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, curated by Gabriel Florenz, Pioneer Works, 159 Pioneer Street, Brooklyn, through December 11, 2022

• • •

Over the past twenty-odd years, global flows of money and labor have shifted, eddied, and reversed with respect to Pakistan. The destabilizing effects of the US War on Terror and the invasion of Afghanistan have meant that fewer foreign tourists avail themselves of the country’s natural and historical splendors. Trump’s 2017 “Muslim Ban” was only the most spectacular instance of what amounts to decades of visa restrictions for people from the Middle East and South Asia, which has meant fewer Pakistan nationals are able to travel abroad. And there has also been a great deal of “return migration”—including by those who were lured by higher-paying jobs in wealthier nations and have decided to come home, flush with cash and used to the luxuries of life in the Gulf or the West.

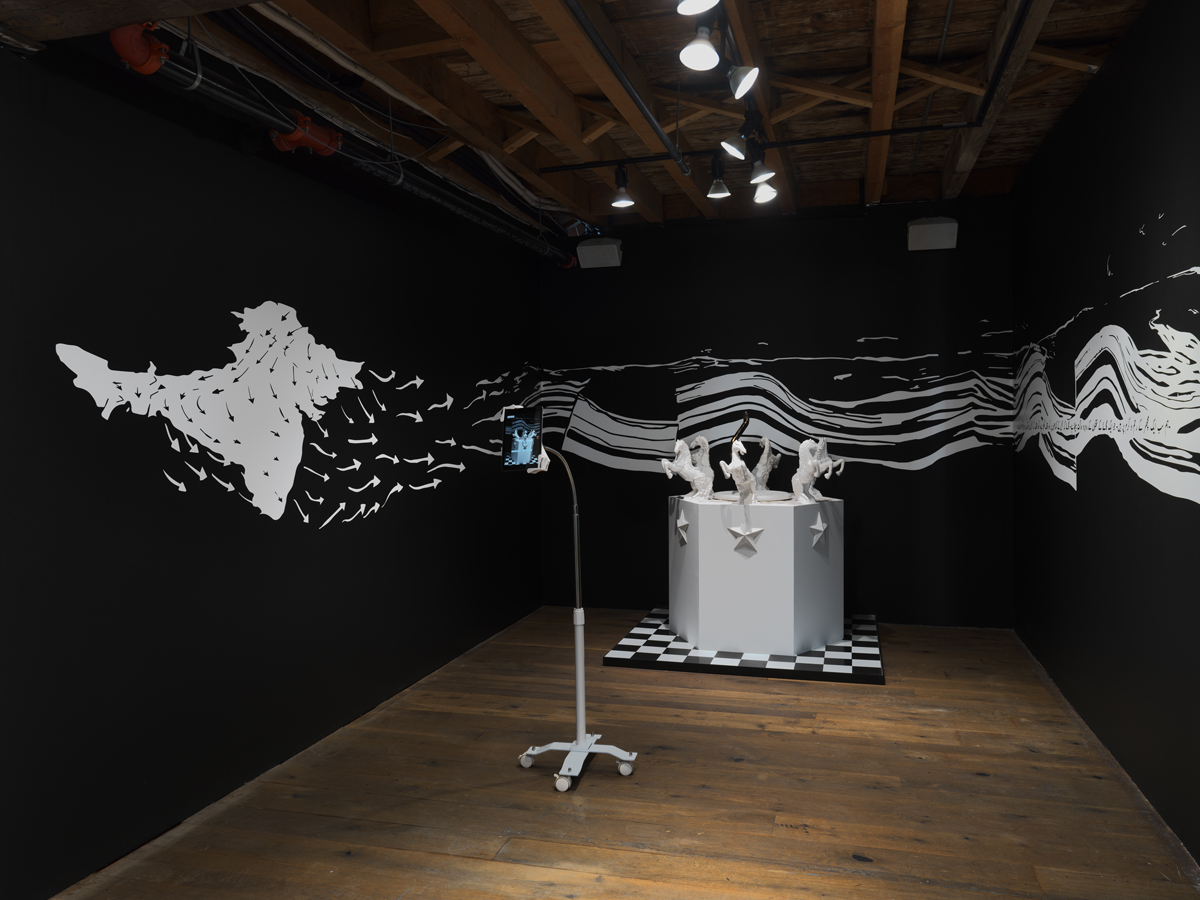

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Gorah ki chowk (Horse Roundabout), 2022. Ceramics, wood, plaster, vinyl tiles, Unity AR software.

Umber Majeed has been tracing these currents in a project called Trans-Pakistan Zindabad (Long Live Trans-Pakistan); its latest iteration, Made in Trans-Pakistan, is now on view at Pioneer Works. Majeed draws upon two seemingly unrelated events—one deeply personal, the other national, and even international, in scope—and uses a variety of media, including ceramic sculpture, augmented reality, and video, to bring to the surface ways in which those events are interconnected: on one hand, the collapse of her uncle Haroon Waheed Pirzada’s travel agency, Trans-Pakistan, in 2005, due to tourism’s decline, and on the other, the growth of deluxe gated communities catering to the monied émigrés who have made their way to Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, and other urban centers. Bahria Towns, the developments Majeed focuses on, have expanded through illegal land grabs that have displaced, sometimes violently, centuries-old neighborhoods and replaced them with shiny, new, heavily policed tracts of housing and awe-inspiring amenities. They are currently home to over a million people—a recolonization or neo-colonization of the country by capitalism on behalf of those who, because of the long-term effects of the British Raj and neoliberal economics, were forced to leave a generation or two ago in order to make a living.

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured, right: Yeh Lo, 2022. Lenticular print, 30 × 20 inches.

Trans-Pakistan Zindabad takes the form of speculative fiction: What if Pirzada’s travel agency still existed? This chapter of the project, Made in Trans-Pakistan, opens with two pieces on either side of the entry to the small gallery that houses the main part of the show: a short, looped video, Fotocopy.net (2021), and a lenticular print, Yeh Lo (2022), whose title translates roughly as “take this.” Centered on the original logo for the agency, both function as calling cards of its reincarnation. The works adopt an aesthetic that Majeed, in interviews, has referred to as “South Asian digital kitsch”—a mashup of pixelated elements defined by shifts in color, scale, resolution, and style that’s instantly recognizable to those familiar with the subcontinent. Fitting for a moment in which tourism has been made nearly impossible in Pakistan, they announce their offerings to be none other than Bahria Towns—places to which the public is given limited access to view their wonders: replicas of monuments including the Sphinx, the Taj Mahal, the Eiffel Tower, and the Statue of Liberty. If Pakistanis cannot easily travel to the world, the world travels, in such simulacral communities, to Pakistan.

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured, left: Fotocopy.net, 2021. Video, 30 seconds.

This seemingly small exhibition uses the logic of the hyperlink to push the viewer out into an expansive universe. Fotocopy.net is a 3D interactive web environment in which one can complete connect-the-dots puzzles based on cute animal sculptures hung above waste-water lagoons that sit outside the Bahria Towns’ entrances to distract from the off-putting realities of these otherwise picture-perfect locales. At Pioneer Works, an NFT minted from Fotocopy.net offers an image of a blue man traversing a spinning globe that occasionally, and abruptly, reverses the direction of its rotation; the tagline “experience a touch of culture with every pixel” floats across the screen, as does, paradoxically, the word “mobile,” rendered in the manner of cell-phone advertisements. (Not coincidentally, cell phones are the only things visitors can bring into Bahria Towns, for security reasons.) What kind of mobility is being offered—not just to the Pakistanis who are the immediate subject of the work, but to all of us living in this strangely connected world of ours?

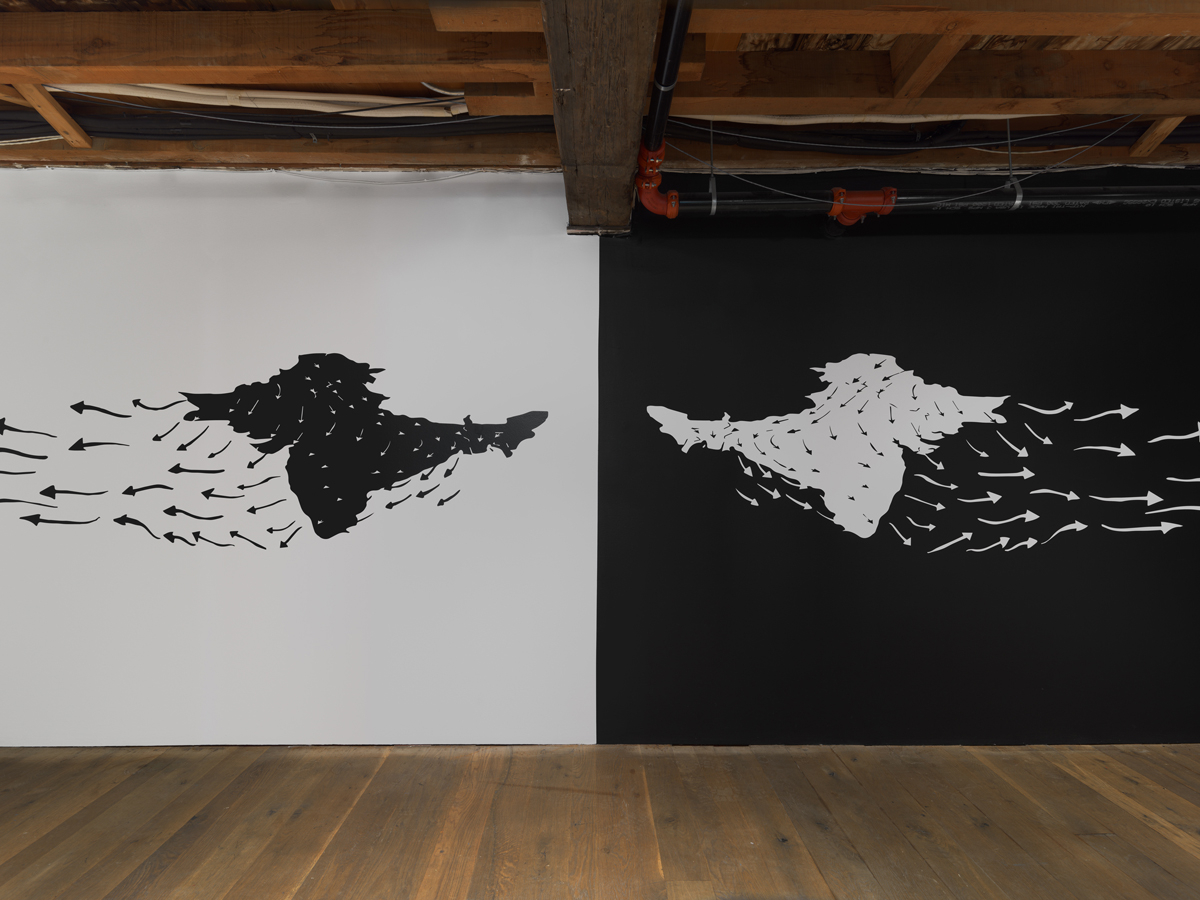

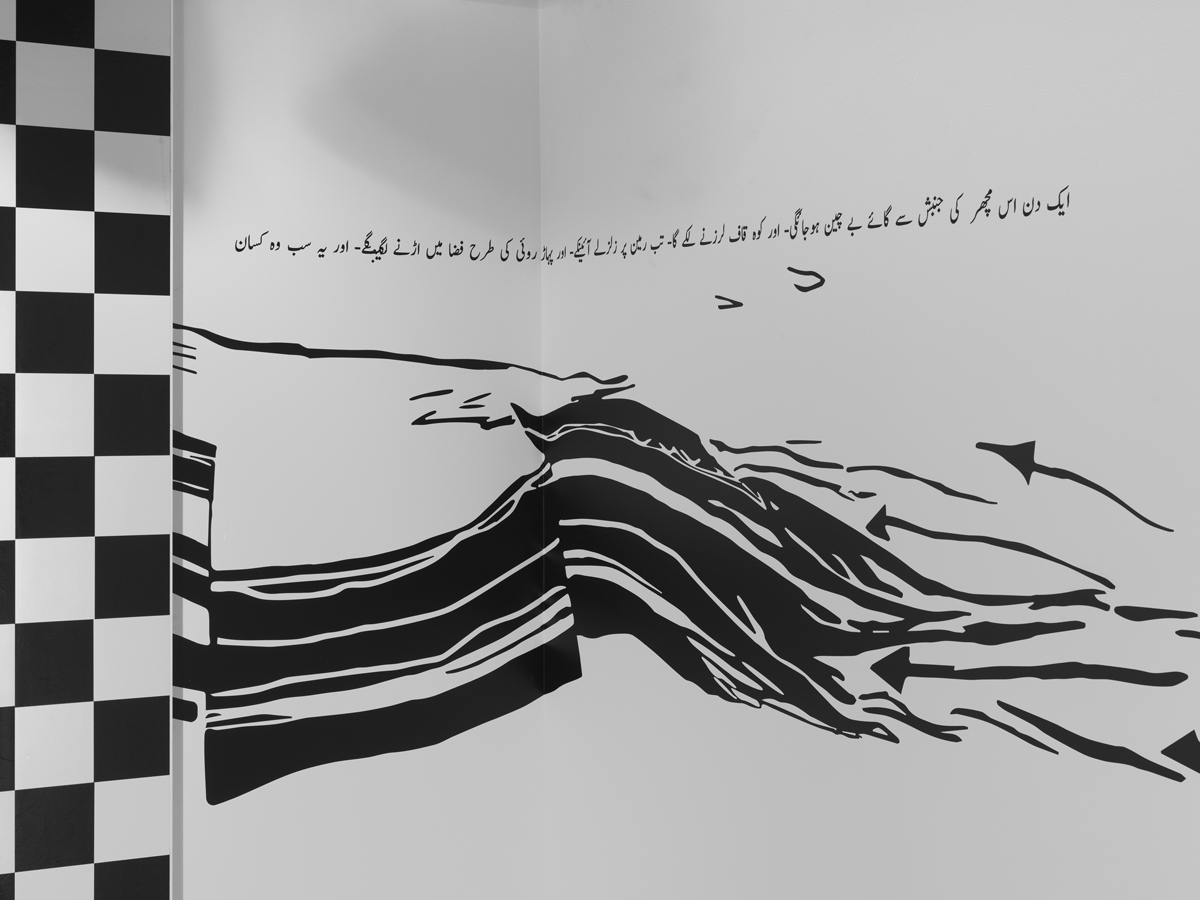

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Umber Majeed in collaboration with Asad Alvi, Untitled, 2022. Vinyl, 48 × 887 3⁄4 inches.

Half the gallery’s walls are painted black and the other half white, each side adorned with vinyl graphics (black on white on one half, and, reversed, white on black on the other) depicting the subcontinent with arrows emanating from it. In both cases, the arrows point outward, toward the west, and eventually coalesce into a Pop-ish painted brushstroke, like a glitched Lichtenstein, alongside Urdu phrases. On one side of the room is Black mai chaiye, yah white mai? (Do you want it in black or white?) (2022), composed of a tiled platform that runs up one wall; look at the live feed of the gallery on the accompanying tablet and you will see, thanks to augmented reality software, words, images, and diagrams floating in space against the checkerboard stage set. The title of the piece and much of the text on the wall and in the virtual environment (the latter appearing in Urdu script and transliterated into Roman) refer to familiar words and catchphrases one hears in Pakistan’s urban marketplaces—“you want it in black or white?” “the name is enough!” “it’s a first copy, a first!”—all referring, obliquely or directly, to the circulation of pirated goods and counterfeits. (The texts have been translated and glossed by the scholar Asad Alvi in a document available via a nearby QR code.)

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Umber Majeed in collaboration with Asad Alvi, Untitled, 2022 (detail). Vinyl, 48 × 887 3⁄4 inches.

On the opposite wall we find Gorah ki chowk (Horse Roundabout), consisting of a hexagonal plinth atop which rear a circle of ceramic horses; at the center is a pipe that bends its way upward. Again, one is encouraged to view the space via a mounted tablet; the screen shows animated plumes of plastic shopping bags spouting like water from that pipe and crude butterfly shapes flitting about. The sculpture is a replica—an unauthorized copy—of ones that sit at the centers of well-manicured roundabouts across the country. Another QR code links to a set of videos, hosted on the Kitchen’s Video Viewing Room, that provide virtual “tours”—concocted by this speculative Trans-Pakistan travel agency and narrated by Majeed—of the various Bahria Towns, including one outside Karachi, with its very own faux Trafalgar Square.

Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Gorah ki chowk (Horse Roundabout), 2022 (detail). Ceramics, wood, plaster, vinyl tiles, Unity AR software.

Pakistani families who cannot afford to live in Bahria Towns are permitted access to their real-world tourist attractions only after extensive security screenings. Majeed’s invitation to visit via digital technology defies the corporation’s attempt to limit and control mobility into and within its development. Despite the geopolitical turmoil that might prevent travel to Pakistan (and now, after the floods that recently devastated the country, environmental disaster brought on by unimpeded industrialization), we can go to Pioneer Works to visit a replication of a replication in an augmented reality facilitated by a travel agency that is an imagined revival of a lost original. In Majeed’s hands, the continual degradation of the original through the copy does not result in a lamentable distance from experience, but another modality of it—a pirated experience, one could say, snatched from the clutches of global capitalism.

Aruna D’Souza is the 2022–23 W. W. Corcoran Professor of Social Engagement at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, DC and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.