Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In the artist’s new sculpture show, it’s mud, trees, and European modernism.

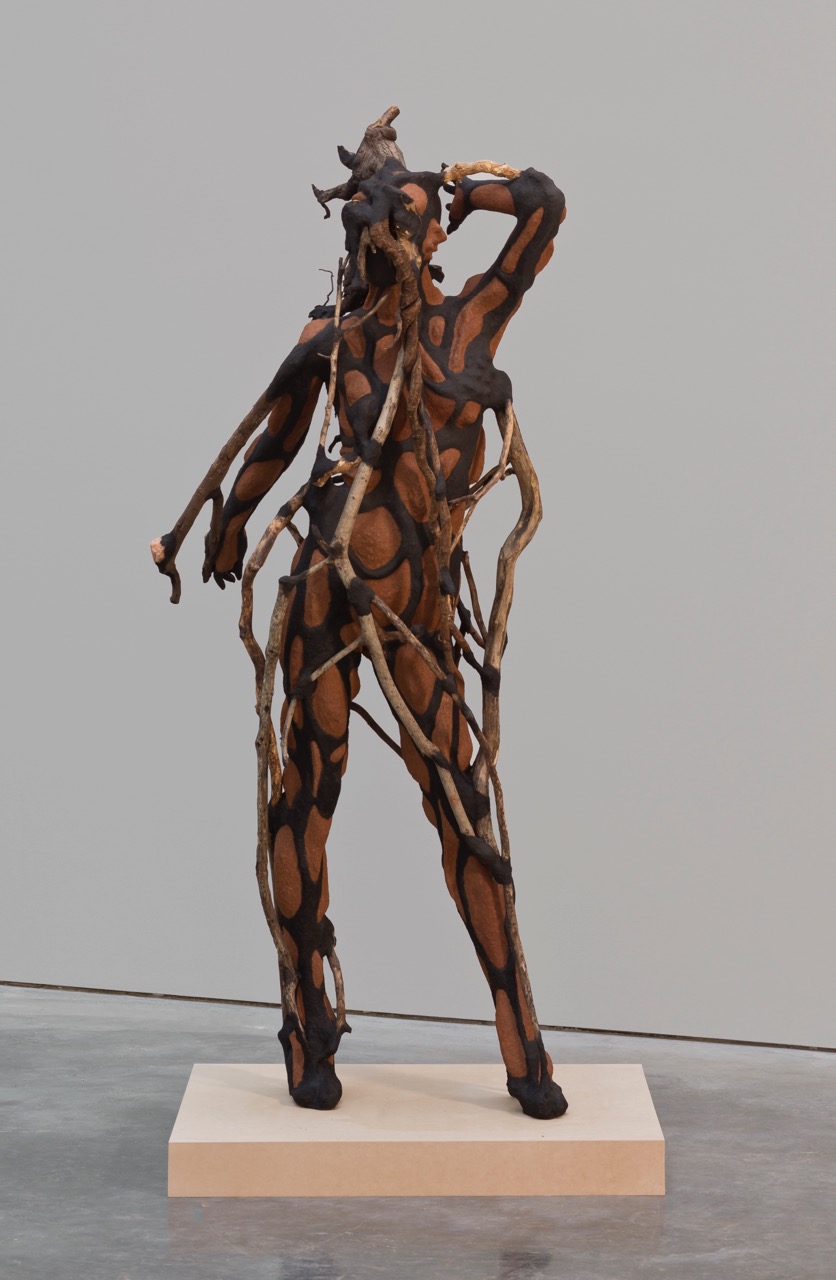

Wangechi Mutu, Ndoro Na Miti, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: David Regen.

Wangechi Mutu: Ndoro Na Miti, Gladstone Gallery, 530 West Twenty-First Street, New York City, through March 25, 2017

• • •

At the far wall of Wangechi Mutu’s exhibition at Gladstone Gallery, among an array of much larger objects, rests a small but irresistible sculpture—a self-portrait, the press release informs us: a cast-bronze head, neck attached, lying on a rough-hewn wooden pedestal. The bust’s smooth cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and full lips are shone to a golden high gloss that gives way to ripples of braided hair, left unpolished and thus dull brown, as bronze is wont to do.

Wangechi Mutu, This second Dreamer, 2017. Bronze and wood. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The piece is called This second Dreamer (2017)—the title alludes to Mwotaji (“the dreamer” in Kiswahili), a smaller version from 2016. But there is another “first” at play here, too: Constantin Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse of 1910, to which Mutu’s piece bears a deliberate and striking resemblance. For the next twenty years, the Romanian-French modernist played with the elemental form of the egg in this series, which he usually cast in bronze or carved in polished marble. The muses’ refined, machine-age finishes deliberately contrasted with their bases, stacked pedestals hacked from blocks of wood or chipped from stone meant to evoke African masks and “fetishes,” Native American totems, and Oceanic tiki figures. In Mutu’s hands, Brancusi’s dream of the Primitive becomes the basis of her own self-fashioning: the face and hair of her dreamer are emphatically Africanized, but the support on which she lays, far from indicating an art untouched by the refinements and corruptions of the modern world, as Brancusi’s pedestals do, looks like something you could buy at a high-end furniture store.

While sculpture has always played a role in Mutu’s career, she is best known for her large-scale collages that combine drawing, watercolor, paint, pictures cut out from magazines, and photographs. These hybrid, sci-fi-meets-fantasy pieces accrete, to an almost obsessive degree, stereotypes of black womanhood until they implode into a dark energy that is as critical as it is erotic. She doesn’t reject these stereotypes so much as lay bare the complexities of forming oneself as a subject within their terms—in all their high-heeled, Beyoncé-assed, lip-glossed glory. In this show, instead of negotiating the fantasies of the black female body as revealed through popular culture, Mutu takes on those conjured by European modernism itself. “Takes on” in both senses: she challenges their racist underpinnings and adopts them, devising herself in their image.

Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse, despite Mutu’s claim of its first-ness in the title for her own work—This second Dreamer—is not a simple point of origin: it too had an antecedent, namely “Africa.” Mutu—an artist of our globalized twenty-first-century world, born in Kenya, raised in England, trained and for some time living in the US, and now based in both New York and Nairobi—stands in peculiar relation to the Brancusi sculpture (and, by extension, to the European modernist tradition) on which she bases her self-portrait. She is dreamed by the Brancusi even as she dreams of the Brancusi: she is what came before the work (the fantasy of African womanhood foundational for European modernism) and what comes after (the fantasy of African womanhood that European modernism produces). Mutu’s self-portrait—this gleaming, ovoid head, at once decapitated and complete—is thus something of a time-traveler, an Afrofuturist recuperation of one of the iconic works of twentieth-century art.

In other words, This second Dreamer is not spawned by Brancusi’s antecedent. This deceptively simple object does many things, but what it does not do—to its great credit—is construct a lineage; its logic is not reproductive (in the way that one creature begets another, its traits and genes passed down according to a chronology of generations), but replicative, in the way of viruses: endlessly reproducing itself within its host, dependent on the host’s DNA for its very form at the same time as it slowly kills it. These are two very different modes of narrating the history of art, and Mutu underlines the point via the most abstract pieces in the show—untitled works she calls, parenthetically, “viruses”: fourteen large globes mounted on thin metal spikes, whose geometric patterns and protrusions recall modernist sculpture, asteroids, and the microscopic world at once.

Wangechi Mutu, Tree Woman, 2016. Red soil, paper pulp, wood glue, and wood, 76 × 34 × 20 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The exhibition as a whole is titled Ndoro Na Miti, Gikuyu words meaning “mud and trees”—the primary (but not exclusive) materials used for the “viruses” and most of the other pieces on view. One finds a massive string of prayer beads, crafted from mud and paper pulp; mud-and-tree portrait busts, including one—Dream Catcher (2016)—sporting a twiggy scaffold emerging from a woman’s head; and a larger-than-life-sized Tree Woman (2016) posed with thrust-out hip and stiletto heels covered in vines that seem to sprout from and encage her body, looking like she has stepped out of the primeval mud straight onto a fashion runway. This wood, like the reddish soil that makes up the admixture of these sculptures, was gleaned outside Mutu’s studio in Nairobi before making its way to New York. The site-specificity of her materials remind us of other moments of displacement of Africa to the US—and the fantasies that both produced and resulted from that violence.

Wangechi Mutu, Water Woman, 2017. Bronze, 35 × 53 × 70 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: David Regen.

These materials are a far cry from the smooth bronze of This second Dreamer and the ebony-black patina of Water Woman (2017)—an arresting, stylized sculpture of an nguva, a water-woman of East African folklore with webbed hands and a fish tail, posed as if for an editorial layout in Vogue. They are a far cry, too, from the felt blankets (often used to wrap artworks during transportation) that are molded into plinths for some of the viruses and shaped into vulvar—or do I mean volcanic?—forms to surround the security cameras in the four corners of the gallery in a way that renders them impossible to ignore. So surprising was their presence for some that I heard more than one visitor ask if it was normal practice for art galleries to have surveillance cameras installed. (For the record: yes, it is.) One of my favorite moments in the show, Mutu’s move interrupts the play of fantasy and mythology (both those of African cultures and of the West) that fuels much of this work by bringing us, the viewers, firmly into the now, and moreover into a space of surveillance, where we are not allowed simply to reflect on the Other but must confront the fact that we, too, are being seen.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and The Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson.