Moyra Davey

Moyra Davey

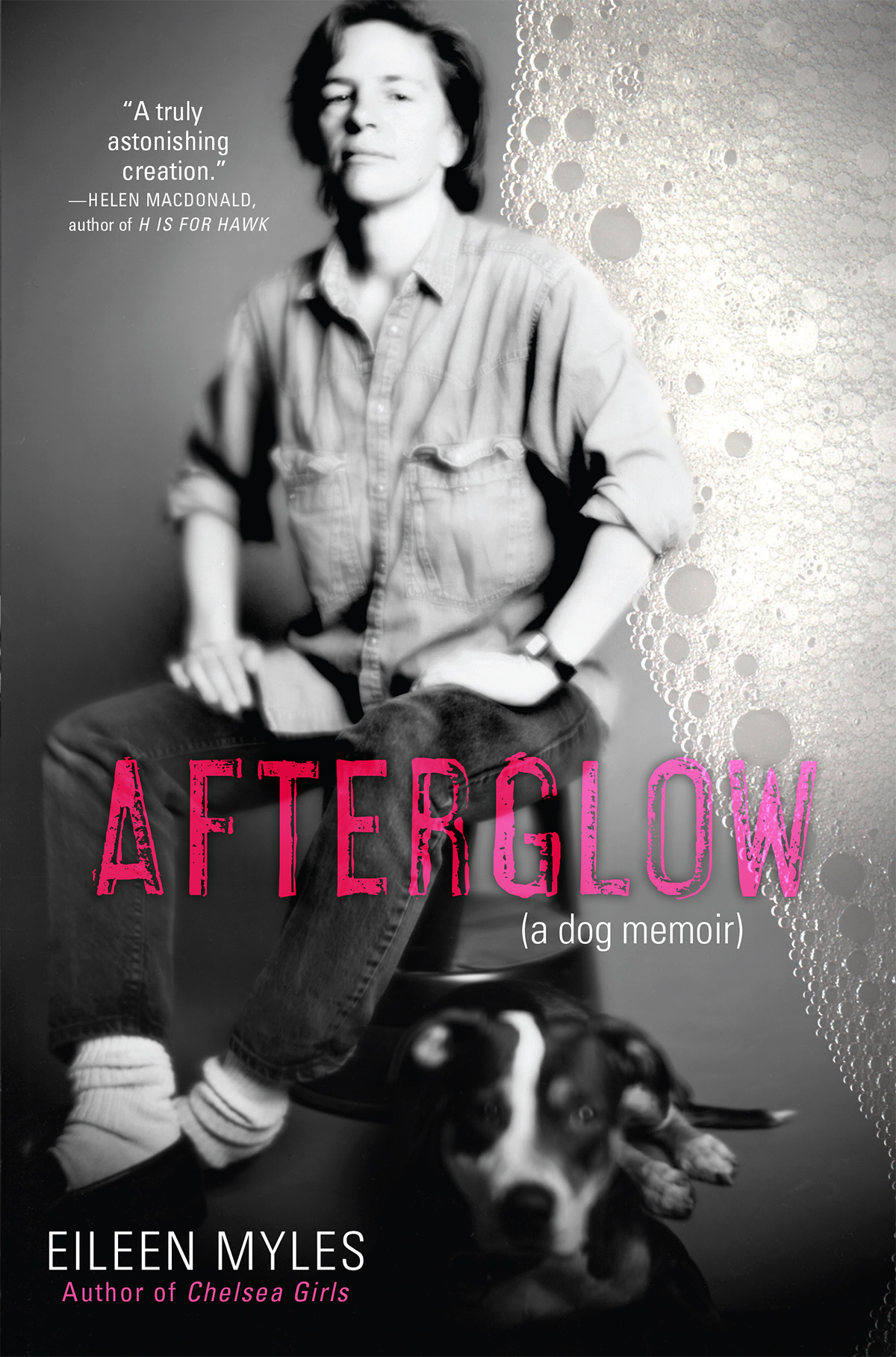

The death—and life—of Eileen Myles’s beloved pit bull inspires the writer’s newest book.

Afterglow (a dog memoir), by Eileen Myles, Grove Press, 207 pages, $24

• • •

After reading Eileen Myles’s previous work of prose, Inferno (A Poet’s Novel), written in a style that is consummately seductive and infectious, I asked: “How can one not write like this?” What is so compelling about Inferno is the permission the author assumes to include everything, to upload it all, not exactly a stream of consciousness, more like some astonishing, sui generis form of ADD. (The epigraph to Inferno is a quote from Walter Benjamin: “The distracted person, too, can form habits.”) Myles’s playfulness with syntax and grammar, the near-banishment of the comma and love of non sequitur, force a close read, with frequent moments of exaltation and quasi-erotic stimulation of the pleasure cortexes of the brain.

In Myles’s new book, Afterglow (a dog memoir), the poet-author writes, “It seems you should obviously always be pleasing somebody with your writing but who.” Myles’s readership has broadened well beyond the East Village poetry circuit, and it is my hunch that that audience is being tested with a more demanding, experimental form. Myles did not want to follow up Inferno with another page-turner, a genre unbefitting Afterglow’s subject: the death and afterlife of the author’s beloved pit bull, Rosie. Instead the writer slows it down and complicates the narrative arc in a way that is challenging, at times to the point of bafflement, but ultimately worth it.

Afterglow begins with Rosie’s death at age sixteen. Incontinent, unable to walk, skin and fur rotting, Rosie’s body is failing and Myles tends to her with a devotion beyond reason. The floor and furniture are draped in towels, the washing machine runs twenty-four seven, Myles bathes Rosie’s butt after each “accident,” and writes about the caretaking and the dog’s decrepitude with a forensic tenderness. Surrounded by friends, Rosie is hand-fed a last meal of carne asada before receiving the gentlest of mortal assists from her vet. The writing that comes after is essentially a work of mourning, but one laced with hilarity and absurdity.

For a start, in the late-stage ministrations it is revealed that dog is god. This is one of many transmutations/migrations of bodies and souls across gender, species, and generations elaborated in the collection of heterogeneous chapters that make up Afterglow. Eileen is a man; Eileen’s father, Ted, a mailman by heredity, is reincarnated as Rosie; eventually all mail carriers are dogs; Eileen’s mother, Genevieve, is the wind rushing through trees. One of Rosie’s final appearances is as deus ex machina to a seemingly blocked Myles. You are a weaver, she tells the writer: think tapestry, rug, The Hunt of the Unicorn, resplendent with faces of humans and hounds. String it all together. And this duly becomes the memoir’s method.

Afterglow wanders in time and place, conjuring enigmatic (at times inscrutable) frames of reference and genres that remind me by turns of écriture féminine, Sun Ra, sci-fi, free jazz, George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog” (plus the myriad dog cartoons of popular culture), Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and finally R. Crumb. I know most of these references are straight, some macho even, but as Myles has queered Rosie and most of the book’s subjects in a way that’s not so easy to pin down, it gave my imagination a green light to roam and alight in eccentric spaces.

Rosie was a companion dog and Afterglow is a companion text. From Ireland, where later segments of this mostly nonlinear chronicle take place, Myles writes: “I’ve set something in motion I can return to again and again. Anywhere.” One day Myles forgets to bring a pen to the dog park and discovers it’s possible to write on the phone, and that it can be done in a pickup truck as well, with infirm Rosie riding in the back. Myles videotapes their final, hobbled walks together and narrates the footage. On one such occasion Rosie is heartbreakingly rendered as the scavenger of a chicken scrap at the park, which she consumes “business-like like old people do.”

Afterglow is composed of disparate, stylistically discrete fragments, but there are touchstones that structure it as memoir, moments one would reliably expect in such an account. Several chapters, including “The Death of Rosie,” “The Rape of Rosie,” and finally “The Walk,” where Rosie’s ashes are dispersed, made me cry. But Myles’s oblique toughness and humor in imagining Rosie’s inner life are what keep this “dog memoir” from ever tipping into mawkishness. The tone set by Afterglow recalls Woolf’s bemused but slightly aloof affection for Flush, the eponymous canine protagonist of her fictionalized biography of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel. I can’t resist including here extracts of deadpan dog observation lifted from the two books, instances where the pets puzzle over some of their poet-owners’ stranger habits: Barrett Browning’s daily ritual of darkening sheet after sheet of white paper with a charcoal stick as observed by Flush; and Rosie’s existential critique of Myles’s addiction to the yellow pad, where “all the vitality floods onto the page while [the writer’s] existence grows wanner and thinner.”

Darwin, Trotsky, Woolf, Roland Barthes, Jean-Luc Godard (and why not Freud while we’re at it, all pained looks in those home movies except when he’s with his chows) adhere to some notion that only the dog offers unconditional love. This view is not upheld in Afterglow: early in the book, Myles’s relationship to Rosie is characterized as “part discomfort & humiliation and part devotion.” (Which immediately made me think of Chris Kraus’s description of her dachshund, Lily, co-owned with Sylvère Lotringer: “She was our talisman, our victim, our vessel of pure comprehension.”) Interviewed by a puppet on a talk show, Rosie, who’s become a floppy puppet herself in old age, is unequivocal about the dog-human bond: “People have us on leashes. People feed us on the floor. They put us to sleep. People put us down . . . [she] rode me like a car. She was interested in how she abused me—she wrote about it.”

Afterglow is no less “a poet’s novel” than Inferno, and in its twisty, woven way it is as much a love letter to human family as to its canine counterpart. Rosie is the purported subject of the memoir, but lineage is a close second, and the ways Myles finds to connect incongruent characters evince the poet’s signature logic. (The writer once said in an interview “If I know the transitions I can write anything.”) Myles writes about Myles’s parents and their Irish relatives, eventually encountered on their soil, with understated empathy. Ted and his family tree form part of the thirsting human tribe entwined in the polymorphous tapestry, that structuring device provided by Rosie when she swoops in and appears to discuss what the tone of the book should be, canine sentience in action.

Moyra Davey is an artist and writer. She was a participant in documenta 14, and is currently exhibiting photographs and video at the Buchholz galleries in Berlin and Cologne. Her canine companion is a Staffie named Rose.