Jack Gross

Jack Gross

The dark side of surrogacy: Jane Campion returns with a surreal sequel to her crime-drama series.

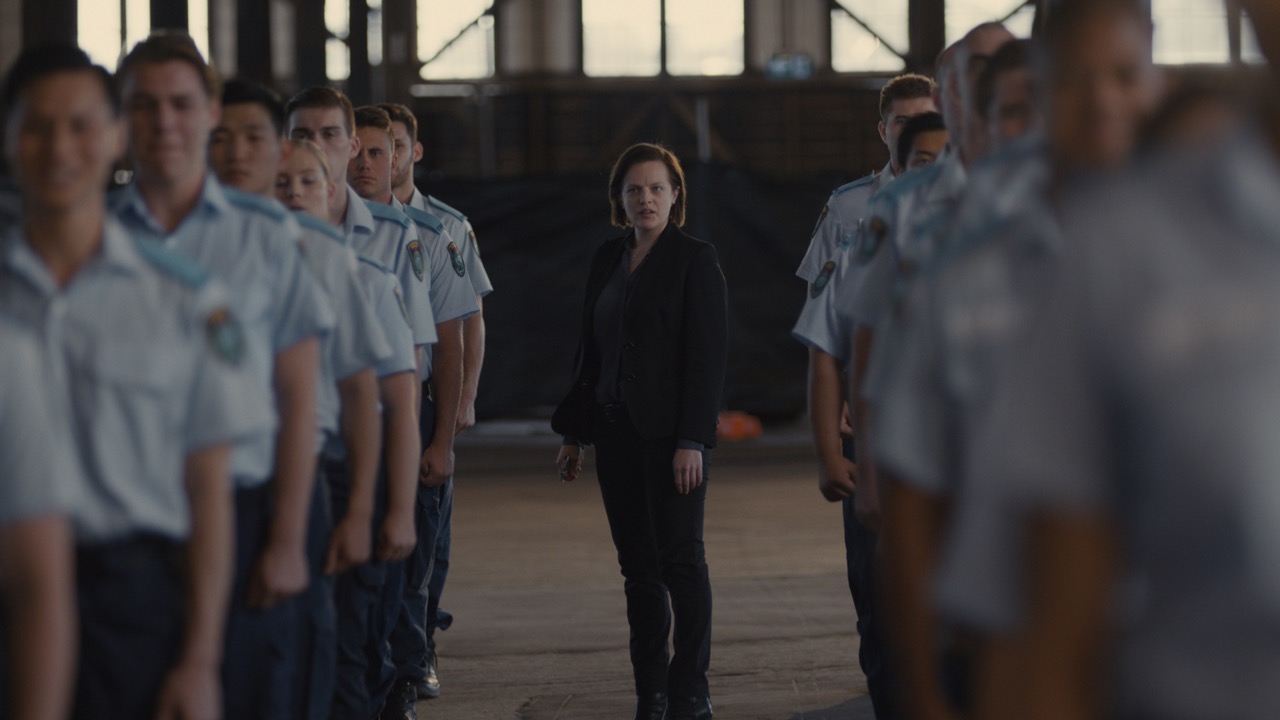

Elisabeth Moss in Top of the Lake: China Girl, season 2, episode 1. Photo: See-Saw Films / SundanceTV.

Top of the Lake: China Girl, directed by Jane Campion, Sundance

• • •

If the crime procedural is the most propagandistic art form, both for its favorable dramatization of law enforcement and its attendant delivery of swift and moral justice, Jane Campion is an unlikely adaptor of the genre. Her most famous film, The Piano (1993), which earned her the only Palme d’Or ever awarded to a woman, was a spare and calmly surreal gothic romance that exemplified a kind of storytelling that shies away from plot—“I’ve never really had an easy time with narrative,” she said in an interview about the film. She favors iconic imagery, richly opaque characters, and moral messiness.

These traits populated Campion’s 2013 TV miniseries Top of the Lake—a widely lauded intervention in the prestige crime-drama landscape that turned a detective story into a hypnotic meditation on sexual violence, misogyny, and community. The series followed Elisabeth Moss as Robin Griffin, a Sydney detective recently relocated to her hometown in southern New Zealand, as she became involved in the case of a missing pregnant twelve-year-old named Tui. As Robin’s investigation unraveled, in Twin Peaks fashion, with layers of crime and culpability lying over the town like a thick fog, what made the series so singular wasn’t Campion’s artful deferral of mystery-solving resolution but the weirdness she injected in the telling of the story.

That weirdness was manifested in a well-funded feminist commune in the small mountain town. Helmed by Holly Hunter as GJ, a parodically rendered self-help guru prone to aphorism, the comedy of this incongruous subplot nonetheless insisted on some of the show’s central questions—where can women be safe?—and provided its most illuminating lines. “The body has tremendous intelligence,” GJ says at one point. “Follow the body.” Cloaked as a new-age maxim, the imperative also describes Campion’s innate power as a storyteller for whom bodies take precedence over words.

Top of the Lake: China Girl, the six-part sequel out on Sundance this month, meets Robin in Sydney, a few years after the conclusion of the first season. (A brief flashback tells us that the move was instigated by a failed engagement preceded by three miscarriages.) She is trying to rebuild a life, navigating the suffocatingly cheery sexism of the New South Wales police department, and preparing to make contact with the daughter she gave up for adoption after becoming pregnant by rape at sixteen. While the subject matter remains as heavy as the first season—delving again into sexual violence, exploitation, and twisted family ties—China Girl’s register is dominated by the offbeat and surreal humor that only occasionally surfaced throughout Top of the Lake. This new season’s many plots intersect in a dizzying, frenzied manner, and its villain provides a strong dose of camp that gives a strange angle to the procedural’s development.

Nicole Kidman in Top of the Lake: China Girl, season 2, episode 2. Photo: See-Saw Films / SundanceTV.

Robin’s daughter, Mary (Alice Englert), now just past the age at which Robin gave birth to her, has spent the years being raised in a large, airy home by Pyke (Ewen Leslie) and Julia (Nicole Kidman). The family is rich, white, and vaguely liberal—consistent fodder for cringe-inducing humor. (“This was her first pony: Sovereign,” Pyke explains to Robin, showing her a photograph of the young Mary.) As Julia has recently left Pyke for another woman, it is also a family in turmoil, and Mary is unrelentingly vicious in her challenges to her parents (“Shove your conventions and your respectability up your cunt, Julia, where nothing has ever lived, where everything dies”).

When Robin meets Mary, they are a strange match. Mary is precocious, funny, and exceptionally articulate; Robin is brittle, guarded, and unsure how to navigate their distance. In their first encounter, Mary tells Robin not to feel bad about an unanswered letter she sent years earlier asking if she could meet her birth mother, and says, dryly, about the unknown rapist who fathered her, “I’ll even kill him if you like. Born to revenge. My daddy was a rapist and then I shot him dead.” And, without a beat, “I like you.” Their bond proceeds with a tentative trust that builds gradually across the subsequent episodes.

David Dencik and cast in Top of the Lake: China Girl, season 2, episode 1. Photo: Lisa Tomasetti / SundanceTV / See-Saw Films.

The relationship is set against the fraying one between Mary and her parents, under particular stress because of Mary’s new and much-older boyfriend, a forty-something German man named Alexander, but who goes by “Puss” (played by David Dencik). A nihilistic pseudo-intellectual whose ceaseless commentary is like an acerbic chorus (“Elegance, but at what cost?” he asks of chandeliers produced with child labor), Puss lives above a brothel called Silk 41 and acts as an English tutor to its mostly Thai sex workers. Unsteadily bearing the villain mantle, Puss is fragile, manipulative, and violent (toward both Mary and the women in the brothel). One of these women is Cinnamon, whose dead body, locked in a suitcase, washes up on Bondi Beach after having been dreamily filmed bobbing in the sea, with long strands of black hair trailing out of it.

Top of the Lake: China Girl, season 2, episode 1. Photo: See-Saw Films / SundanceTV.

The new season kicks into gear as a police procedural when Robin and her new partner Miranda (Gwendoline Christie) are assigned to the case. They discover that Cinnamon was pregnant, but it is quickly revealed that the fetus bears no genetic relationship to her—that she was a surrogate. Robin’s investigation leads her to an expensive IVF clinic, some of whose clients have turned to an illegal surrogacy operation run out of Silk 41 and managed in part, we learn, by Puss.

The global trade in surrogacy can be read as a stark miniature of the class and race exploitation that maintains the bourgeois family form. Campion’s depiction of the industry reflects this, showing us desperate and wealthy Australian couples employing poor, fertile women from the global South to carry their offspring to term. This dynamic is baked into the show’s form: elements of the family drama, an endless source for canonical art, are plotted alongside the violence done directly and indirectly in the name of the family. But Campion’s critique is ambivalent—the intended parents’ fertility anxiety is both mocked and made sympathetic, like Julia’s anxiety over her fraying relationship with Mary.

China Girl’s structure will likely frustrate some fans of the first season’s comparatively credible linearity. But with a richly layered series that leaves several threads untied—we never really get an answer to the question Robin poses to Cinnamon’s body on the beach, “Want to tell me what you saw?”—Campion offers another season of mesmerizing storytelling that skewers her adopted genre.

Jack Gross is a writer in New York and Toronto.