Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Coltrane, Coleman, Dolphy’s death: a documentary charts the 1960s’

free jazz movement.

Sun Ra in Berkeley, CA in 1968, as seen in Fire Music. Photo: Baron Wolman. Courtesy Submarine Deluxe.

Fire Music, directed by Tom Surgal, now playing at Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City; and other select theaters

across the country

• • •

Fire Music’s energetic opening sequence depicts a kaleidoscopic, raucous vintage performance by the Sun Ra Arkestra. A drummer grabs a cymbal on a stand, turns it upside down, and begins crashing it into the stage. A Karl Marx quote materializes on the screen a few minutes later: “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

This chaotic, dynamic new documentary on free jazz, directed by Tom Surgal, plays like a striking riposte to Ken Burns’s staid, gargantuan ten-part series Jazz (2000). That series, for the most part, was a tidy, mainstream version of jazz history, engineered for a crowd more accustomed to Lincoln Center than a downtown club. Fire Music, which takes its name from a spirited 1965 album by the saxophonist Archie Shepp, works to issue a corrective to the prevailing uptown narrative. “The new mainstream has attempted to erase the innovations of the avant-garde from jazz history,” the film declares. Fire Music centers on key artists in the outer reaches of the genre in the 1960s, who pushed jazz forward into wild new terrain.

Surgal is known for directing music videos for bands such as Sonic Youth and Pavement; he is also an experimental musician who has played in several groups, including the band White Out. He has long been an avid collector of free jazz albums, and Fire Music is his first feature-length film. The movie, which was bootstrapped with the help of a successful Kickstarter campaign, comes across as a love letter from an impassioned fan to the music he clearly adores.

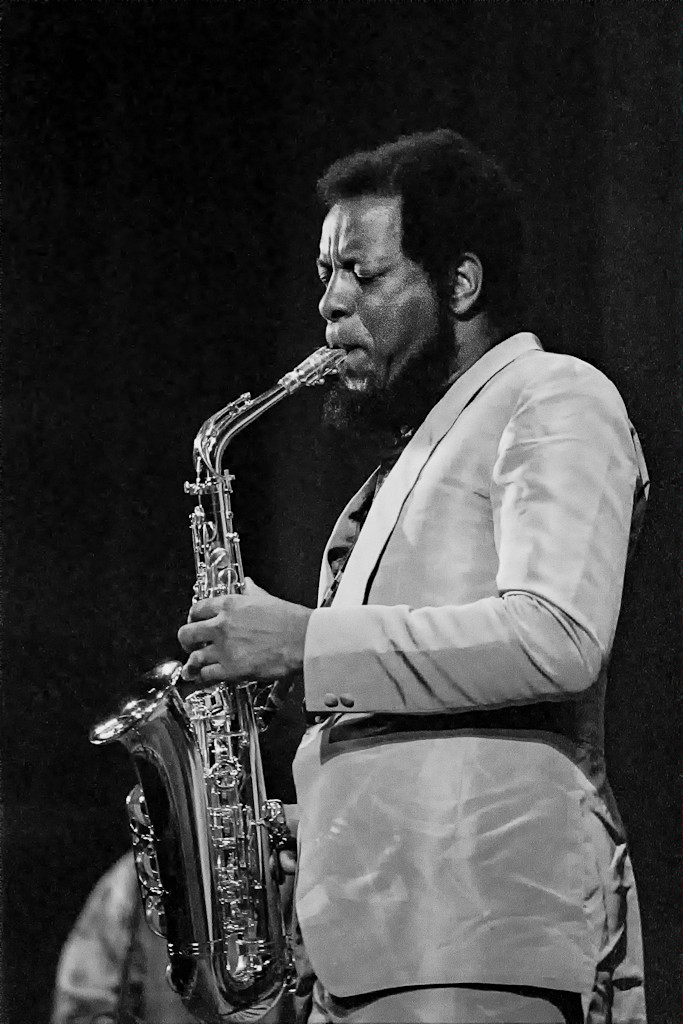

Ornette Coleman performing in 1971, as seen in Fire Music. Photo: JP Roche. Courtesy Submarine Deluxe.

The movie is arranged as a series of brief vignettes of major figures in the development of free jazz, including Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Eric Dolphy, John Coltrane, Sun Ra, Don Cherry, and Albert Ayler. (Many of these musicians received only passing mentions in Burns’s Jazz.) Surgal also includes brief segments on the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the loft jazz scene in New York City, as well as a short primer on European jazz—including the German saxophonist Peter Brötzmann and the Dutch drummer Han Bennink.

In a way, though, Fire Music might be closer to Jazz than it would like to think. Like Jazz, it documents a past long gone by, focusing, for the most part, on more well-known characters. The lineage it tracks may be an avant-garde one, but it’s a canon nonetheless, with its own orthodoxies and omissions.

Carla Bley performing in San Francisco, CA, in 1979, as seen in Fire Music. Photo: Brian McMillen. Courtesy Submarine Deluxe.

The most glaring omission is that only two women are interviewed during the entirety of the film—the pianist and composer Carla Bley and the German singer Ingrid Sertso. While they both provide trenchant firsthand observations, there is almost no discussion of their own creative practices; they’re mostly onscreen to supply anecdotes about prominent male musicians such as Coleman and Dolphy. No other women composers and musicians are even mentioned. There is no discussion of Alice Coltrane, who was a towering figure, nor any of trumpeter Barbara Donald; singer, dancer, and violinist June Tyson; nor of the vocalists Patty Waters and Jeanne Lee, among others. Critical commentary is ably provided by the noted jazz scholar Gary Giddins, but a female writer could have added insights here too. To be fair, several male jazz musicians are omitted from the storyline as well, such as the free jazz percussionist Milford Graves. (That said, Graves was the subject of his own full-length documentary a few years back, the endlessly fascinating Full Mantis.)

Sertso offers the most heartrending anecdote in the film—a vivid recollection of Dolphy’s final minutes (he died suddenly in 1964, at the age of thirty-six). “We brought him to this hotel in Berlin,” she remembers. “He ordered ice cream and juice and Coca-Cola and stuff like that.” Dolphy didn’t know he was diabetic. “He played the first song with us, then he said, ‘Excuse me, I have to go into the dressing room’ . . . the door opened and Eric crawled out, on the floor, and just said, ‘Help me,’ and we immediately brought him to the hospital.” Dolphy passed away shortly after.

The history of jazz is filled with sad stories like this, and Fire Music’s strongest moments come when it explores the human side of the music industry: the poor treatment the musicians often received, and the poverty and squalid living conditions they often faced. It touches only briefly on civil rights and issues of race, with a fierce quote from Shepp on the state of affairs for jazz musicians: “I don’t see how they can get better for Black musicians until they get better for Black people,” he said. “We can’t protect our culture until we can actually alter economic and social institutions to reflect better our needs and our desires, I think.”

John Coltrane performing (year unknown), as seen in Fire Music. Photo: Lee Tanner – The Jazz Image. Courtesy Submarine Deluxe.

Fire Music works creatively with its limited budget, relying heavily on archival material and earlier films. Stunning footage of Taylor playing a Bösendorfer grand piano against a stark white backdrop, and the multi-instrumentalist Bill Dixon passionately discussing the state of the genre with a nearly empty wine glass in his hand, can also be seen in Ron Mann’s fantastic 1981 free jazz documentary Imagine the Sound. (Mann is listed as one of the executive producers on Fire Music.) The black-and-white clips of Charles Mingus are taken from the 1968 documentary Mingus, directed by Thomas Reichman. Fire Music also makes ample use of famous concerts—such as an unforgettable performance of Coltrane playing “My Favorite Things”—and numerous vintage interviews. There are several new interviews, too, but the bygone footage understandably dominates the narrative, as the film centers on the 1960s, and several of the musicians discussed, including Coltrane, Dolphy, and Ayler, passed away several decades ago.

Snippets culled from vintage experimental cinema give Fire Music a dreamy collage effect. Clips from short films such as John Whitney’s Experiments in Motion Graphics (1968), Hans Richter’s Rhythmus 21 (1921), Stan Brakhage’s The Wonder Ring (1955), and Man Ray’s Le retour à la raison (1923) spice up the movie’s more straightforward documentary style with vibrant geometric patterns and abstract images. Old, grainy public-domain footage of New York City’s streets and skyline lend the movie a hazy classic feel, and the film’s typography appears to be carefully selected to be reminiscent of the fonts used in mid-century modern-jazz album covers.

As an introduction to free jazz, Fire Music forms an admirable beginning. But there is still space for a longer, more expansive documentary that takes in the full diversity of the field, that is as open and wide-ranging as the music itself.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.