Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

In the photographer’s new show, noir aesthetics and the work of

Donald Judd.

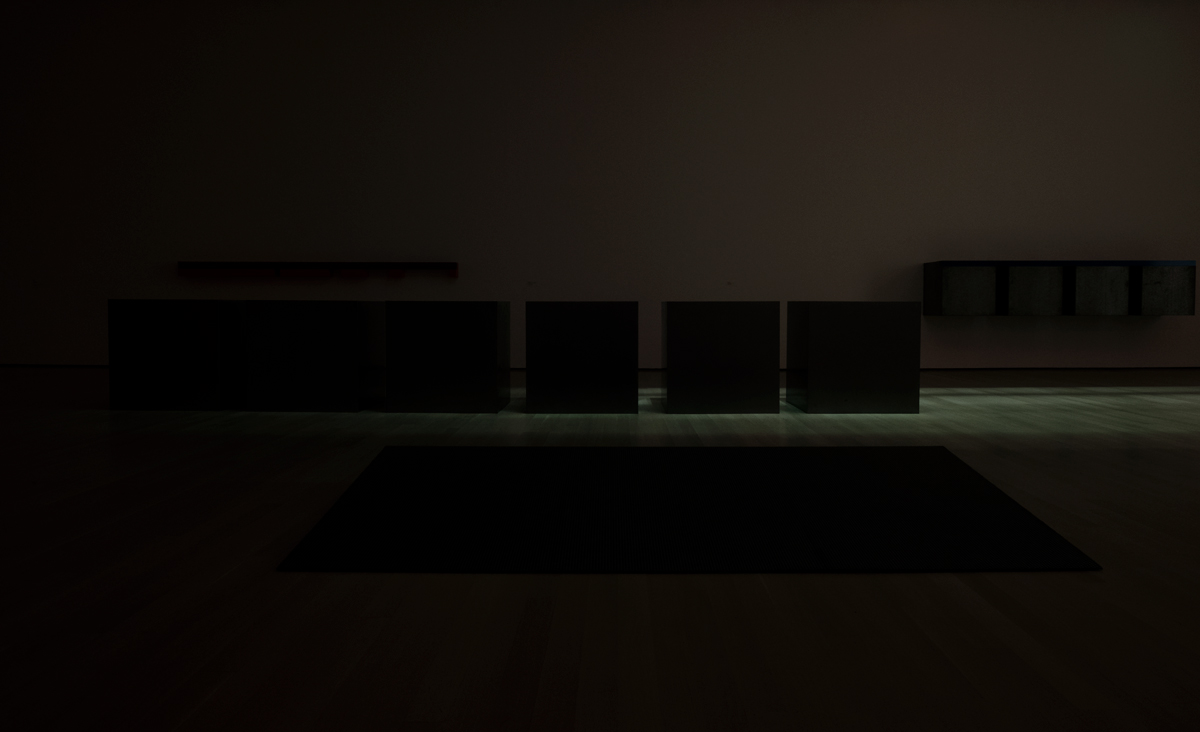

Louise Lawler: LIGHTS OFF, AFTER HOURS, IN THE DARK, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

Louise Lawler: LIGHTS OFF, AFTER HOURS, IN THE DARK, Metro Pictures, 519 West Twenty-Fourth Street, New York City, through

October 23, 2021

• • •

The twelve dark, almost black, photographs of Louise Lawler’s cinematically ominous and truly thrilling new show at Metro Pictures were taken over the course of two evenings at the Museum of Modern Art, after it shut down for the day. Returning to the sixth-floor galleries where her acclaimed survey WHY PICTURES NOW was mounted in 2017, as though to the scene of a crime, the Pictures Generation conceptualist shot the unlit installation of another artist’s retrospective—Donald Judd’s (his first in the US in three decades). Judd opened in March of 2020, languished for months during the lockdown, and closed a few days after the Trumpist convulsions of January 6. Lawler’s long exposures (which are dated 2021, and so must have been taken during that final stretch) capture the smooth silhouettes of the preeminent Minimalist’s work emerging from the sleeping museum’s gloom. The photos form a fitting, forbidding coda to the major exhibition’s strange ten months, and an elegant swan song for the artist. It will be her last show at the gallery—Metro Pictures’ founders Helene Winer and Janelle Reiring announced in March that they would be closing after forty-one years in business, citing “a demanding year of pandemic-driven programming and the anticipated arrival of a very different art world” as reasons.

Louise Lawler: LIGHTS OFF, AFTER HOURS, IN THE DARK, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

Most of the prints in LIGHTS OFF, AFTER HOURS, IN THE DARK are of a good size, though for Lawler they aren’t huge. (She has in recent years often made wall-spanning “adjusted to fit” murals from her images.) The works often evoke big flat-screen TVs with their proportion and finish, and, while it’s not uncommon for large-scale photos to act as mirrors, Lawler uses the reflective quality of her glossy surfaces here particularly powerfully, showing viewers to themselves as inky apparitions transposed onto, or transported into, the deserted rooms of MoMA.

Louise Lawler, Untitled (Cadmium), 2021. Dye sublimation print on museum box, 48 × 71 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

In these eerie settings, the units of Judd’s signature “stacks” are gray bars on gray walls; his famous cadmium red, which usually appears strident, here broods, smoldering on the surfaces of his untitled “boxes”; other floor sculptures read as sharp-edged voids; and shiny industrial materials (aluminum, galvanized iron, stainless steel, plexiglass) catch ambient light leaking into the exhibition from skylights and hallways. There is something mordantly funny at work in these painterly photos, in the way Lawler has patiently coaxed Judd’s “specific objects” (he eschewed the term sculpture for what he saw as a radical new art) from the shadows, recalling Suprematist or Cubist abstractions, as well as the voluptuous tenebrism of Baroque interiors—all the old, European art Judd disdained.

Louise Lawler, Untitled (Skylight), 2021. Dye sublimation print on museum box, 48 × 78 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

The night sky’s green glow haloes a series of rectangular enclosures in Untitled (Skylight); a hazy column of light in the dim, grisaille Untitled (Night) might illuminate a crucifixion—or announce a monster. The fiery glare of an exit sign, spilling onto the ceiling in one picture, and the tiny eye of a ceiling security camera or sensor in another are horror-movie flourishes, taking Lawler’s long engagement with noir aesthetics—and institutional critique—to a new place: one that is less restrained, ironic, or melancholic, and more genuinely terrifying, even apocalyptic.

Louise Lawler, Untitled (Brass and Blue), 2021. Dye sublimation print on museum box, 48 × 71 inches. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

The work looks and feels different, but these pictures are not such a departure for the artist. For over four decades she has photographed art objects in situ—in homes, auction houses, and storage spaces, as well as in museums—highlighting their status as products and property, their unlofty social meanings beyond or in contradiction to their ostensible content. Lawler’s first show with Metro Pictures, in 1982, bluntly titled Arrangements of Pictures, included cropped, fragmented images of historical artworks hanging at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She also presented a related gesture of appropriation, an installation of selected works by fellow artists represented by the gallery (Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman, and Laurie Simmons among them). This time, the “arrangement” was both compositional and financial. Individual pieces sold were subject to a 10 percent markup (Lawler’s fee as a consultant). This semi-satirical commission system complemented the postmodernist and materialist ideas about authorship and interpretation on view; in cutting herself in on the deal, she made visible the usually hidden workings of the commercial gallery system.

Louise Lawler, Untitled (Intervals), 2021. Dye sublimation print on museum box, 48 × 72 inches. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

You can’t keep your hands clean by pointing a finger, her work has always insisted. These days, Lawler’s methods of self-implication are established, reflexive, and ungimmicky—or perhaps they’re simply obviated. The first and most crucial ingredient of LIGHTS OFF, AFTER HOURS, IN THE DARK is, of course, privileged access. The artist was once on the outside—in a 1972/1981 sound installation she rendered the names of famous male artists, including Judd’s, as birdcalls, poking fun at the art world’s unnatural order (particularly its exclusion of women from major group exhibitions)—but here, she jangles her keys to the museum, exercising her symbolic authority to cut the lights to the great man’s show.

Judd’s interrupted run coincided with a new era of trouble for cultural institutions. Ugly labor practices and the unsavory business entanglements of patrons have become more difficult to brush off under the sharpening filter of the pandemic and the hot lights of successive, simultaneous MeToo and Black Lives Matter reckonings. The superlative exhibition Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, organized by Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood, which ran roughly concurrently with Judd, at MoMA PS1, dramatized the gulf between the professed progressive agenda of the museum and the values of its funders: activists have targeted trustee Larry Fink of BlackRock as a private-prison profiteer since 2019.

Louise Lawler, Untitled (Bullnose), 2021. Dye sublimation print on museum box, 48 × 67 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

And I imagine Judd was still being taken down and crated when news broke that MoMA’s board chairman, the billionaire Leon Black, had paid millions annually to Jeffrey Epstein for “tax advice,” after Epstein’s 2008 conviction for the procurement of a child for prostitution. “The art world has some dark corners,” stated the Guerilla Girls at the end of January, as quoted in the New York Times, “and Leon Black lives in one of them.” In the spellbinding LIGHTS OFF, Lawler shows MoMA as nothing but dark corners. It’s not the skeletons, it’s the art that viewers have to strain to see.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.