Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Remembering the one-of-a-kind composer.

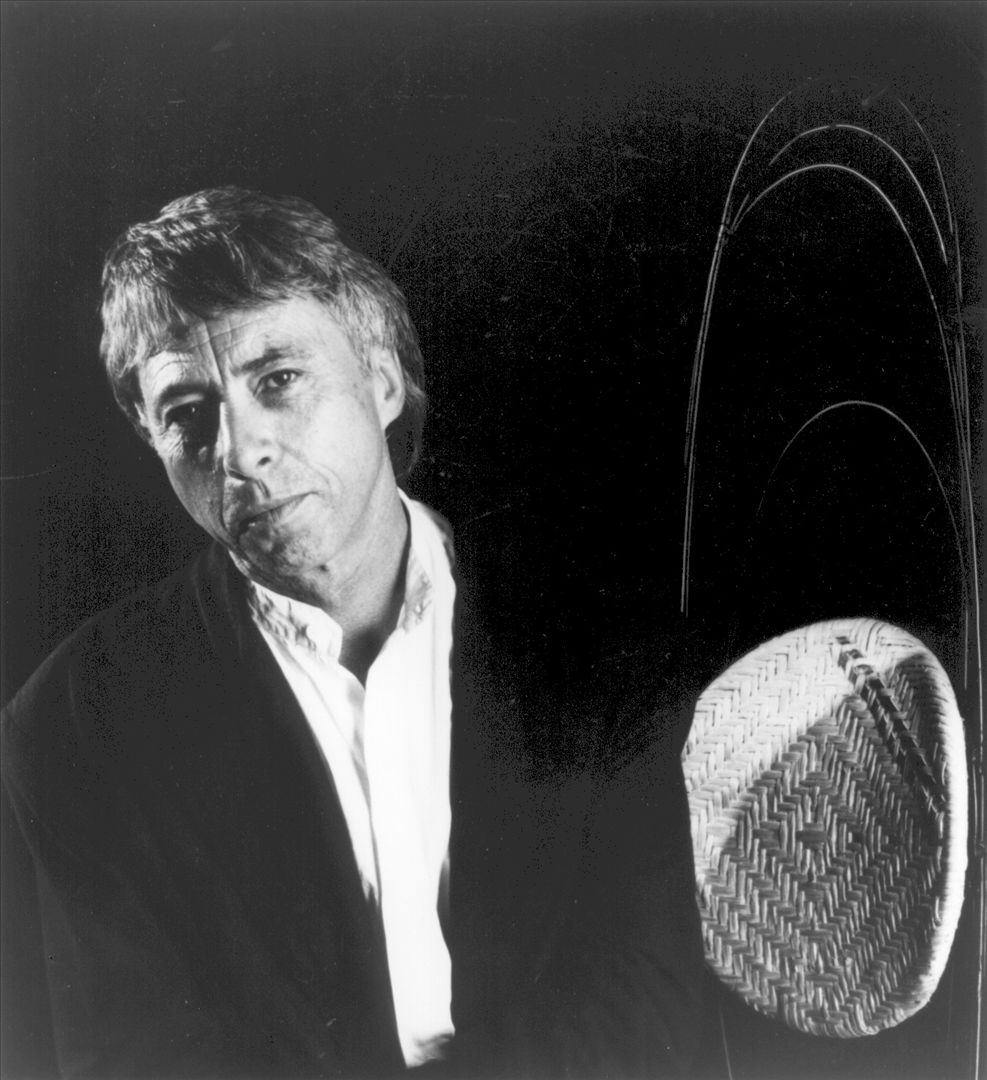

Harold Budd. Photo: Matthew Budd.

1936–2020

• • •

Harold Budd, who passed away in December of complications from COVID-19 at the age of eighty-four, was one of the great composers of our time. He was also one of the most underrated. Budd played numerous instruments, most notably the piano, with a style that was utterly unique. His delicate piano figures could seem simple, but they are far more complex than they initially appear. His music is often described as placid, calming, diaphanous—but it is also intense and occasionally disquieting.

It is difficult to write about him in the past tense. I interviewed Budd several times over the past fifteen years; he was also a friend. When I last talked with him, in a café in South Pasadena before the pandemic began, he shrugged off being in his eighties, and seemed fueled with youthful energy. He was writing new music and had recently finished a multipart work that debuted at the Toledo Museum of Art titled Petits Souffles. Budd spoke animatedly about upcoming concerts and projects, lamented that Joshua Tree, where he lived part-time, was overrun with tourists, and was contemplating a move to France. He was a California lifer, and his mere presence in Los Angeles made the city feel like a magical place.

Budd was born in Los Angeles in 1936, and grew up on the fringes of the Mojave Desert. He was drafted into the army, and briefly played in a band with the late free-jazz legend Albert Ayler. In those days, Budd played the drums. “I learned it as a kid,” he told me in 2018. “I loved seeing the Scottish marching bands on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles during the war. I thought drumming was thrilling.” He became a huge fan of jazz. “Every week there was a club on West Washington Boulevard here in LA with the Paul Bley quintet,” he told me. “So I heard Paul Bley a lot . . . and Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry.”

Budd immersed himself in new sounds outside of jazz, too. “I went to a concert by Cage and David Tudor called ‘Where Are We Going? And What Are We Doing?’ ” he recalled to me in 2008. “I thought, Jesus Christ, I wanted to go in that direction. It seemed heavy with the art part, if you know what I mean. It was heavy anti-academic, anti-Germanic, anti-European modernism . . . Cage was not an antidote to that, but just a different monetary value altogether.”

Budd spent some time in academia, teaching at CalArts. In 1970, he composed an experimental, improvisatory piece using an early electronic instrument, the Buchla box, a work called “The Oak of the Golden Dreams.” The evocative title was a reference to an actual place in Southern California—an oak tree in Placerita Canyon, where a man named Francisco Lopez discovered gold flecks on wild onions in 1842, eventually paving the way for the first gold rush. “The Oak of the Golden Dreams” suggests an alternate path for Budd—he could have traveled further into the realm of meditative synthesizer epics, like many German groups of the time. But while he did sometimes explore electronics, his focus never wavered from traditional instruments.

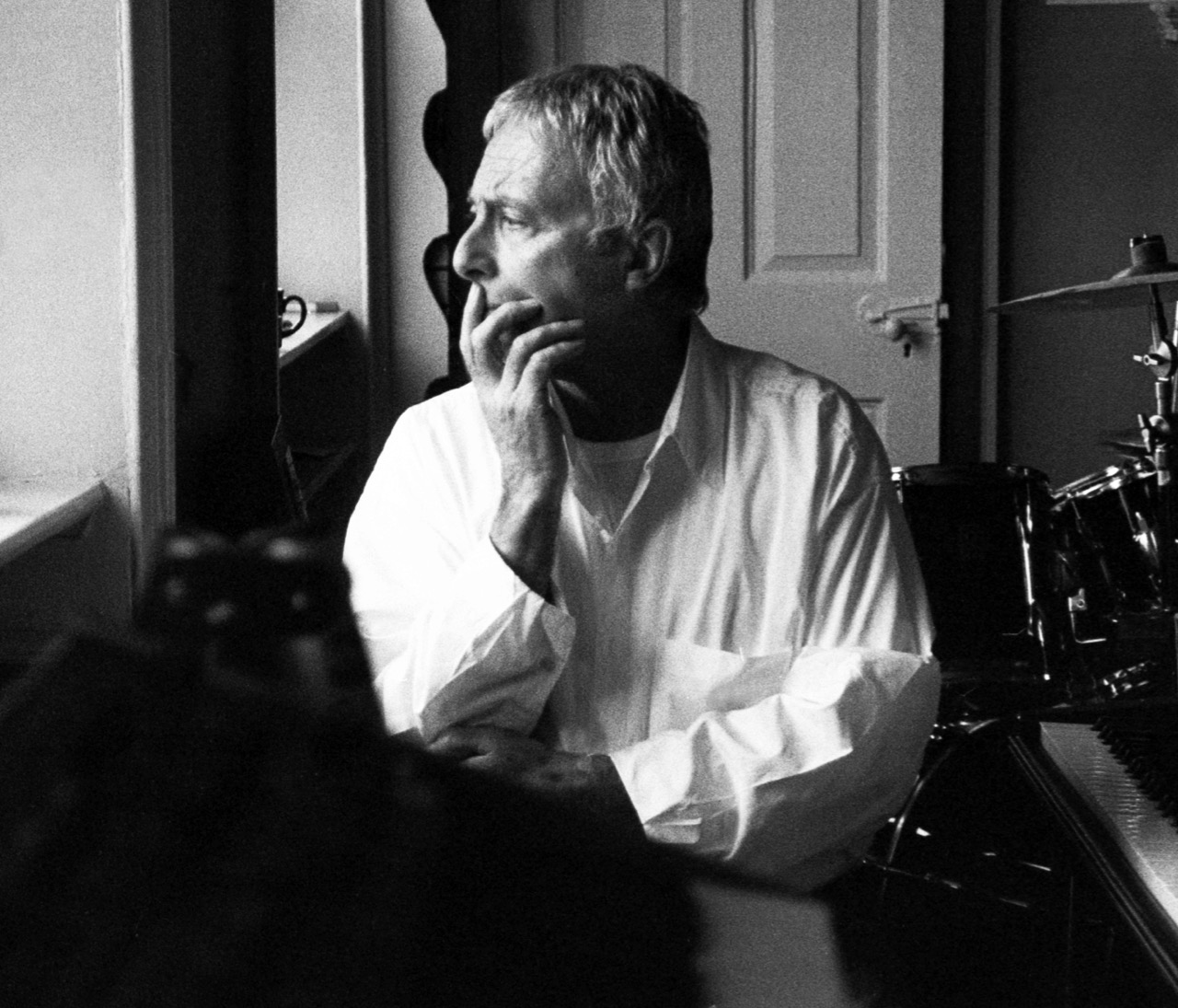

Harold Budd in the mid-1980s. © All Saints Records.

Budd conceived a unique sonic terrain, in part by eschewing what was cool at the time. While other composers pushed the bounds of “difficult” avant-garde music, Budd created gentle, lushly romantic ambient works, embracing the piano and melodious, old-fashioned instruments such as the celeste. He admired abstract painters like Mark Rothko, but also derived inspiration from the far less hip Pre-Raphaelite artists of the mid-1800s, especially the painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Budd’s dreamy early breakthrough “Madrigals of the Rose Angel,” which featured a segment titled “Rossetti Noise,” was deliciously out of step with the hard-edged music of the 1970s. “It was wonderful, that image of a rose angel,” Budd told me in 2008. “Whatever a ‘rose angel’ is, I haven’t a clue, and it certainly isn’t a madrigal, but it’s a combination of words that, to me, is still magic. Absolute magic.” The piece caught the attention of Brian Eno, leading to their landmark collaborations in the 1970s and 1980s, including The Pavilion of Dreams and The Pearl. The albums traveled a wide arc of feeling, filled with moments of extreme beauty, quiet contemplation, deep melancholy, and, occasionally, eerie paranoia. The track “An Arc of Doves,” from the 1980 Budd-Eno collaboration Ambient 2: Plateaux of Mirror, is one of the most sublime pieces of music ever made— celestial notes raining down from a heavenly cloud.

Budd’s style of playing piano was more like painting than conventional music. The notes of the piano, through the soft focus of the sustain pedal, conjure emotions and environments, washes of color and texture. It is ambient music, enigmatic and subtle. His elaborate song titles reflect a flair for language—he penned several books of poetry in addition to his music—and an affinity for visual art. Look back on Budd’s track names and you’ll see layers of references, many to artists that he admired—from Agnes Martin to Odilon Redon to his favorite painter, Billy Al Bengston. “The only thing I ever go into the studio with is a list of titles,” he told me in 2008. “And if I really like the titles, I know it's going to happen. And it does happen. That’s the way it goes. What a wonderful way to live, honestly. The titles, of course, are my version of poetry, I guess, or something like that. They don’t have a rhyme scheme or anything like that, but they’re mostly images, and kind of little things that tend to paint or tint the tenor or the atmosphere of a room.”

Harold Budd. © All Saints Records.

I once asked Budd if he was pleased that so many people found his music soothing, a curative for troubling times. He said he was happy if it gave people solace, but that music didn’t inherently need to serve any kind of function. Music could just be there to be beautiful.

In Budd’s work, I hear California in its wide roads and open spaces. It is music, in this frenetic time, that invites us to slow down. In both his solo albums and in his myriad collaborations with Eno, the Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie, David Sylvian, and others, his sound and approach is singular. Though Budd is no longer with us physically, his work will continue to be rediscovered in the years to come.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.