Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

“I don’t like to tell the machines what to do”: a biography of David Tudor.

Reminded by the Instruments: David Tudor’s Music, by You Nakai, Oxford University Press, 753 pages, $74

• • •

Numerous books have been written about John Cage. While his body of work remains dazzlingly rich, complex, and wide-ranging, it is not impossible to understand. It helps that Cage, who died in 1992, left behind a huge paper trail. He was a tremendous writer who detailed his ideas and methods in books, essays, letters, and poems. He was often in the public eye—teaching and lecturing widely, communicating with the press, and even once appearing on a TV game show.

But the virtuoso pianist and electronic composer David Tudor, whose name appears prominently in hundreds of writings as one of Cage’s most vital early collaborators, remains a bit of an enigma. “David Tudor had always appeared to me as a giant puzzle in the history of twentieth-century music,” writes the Japanese scholar You Nakai, author of the first long book on the entirety of Tudor’s life and work—an impressive 753-page opus titled Reminded by the Instruments. “He was a dweller of anecdotes and hearsays, somehow everywhere and nowhere at once.”

David Tudor blowing whistles, mid-1950s. Courtesy Klüver / Martin Archive. Photographer unknown. All rights reserved.

Tudor has a striking presence in vintage black-and-white photographs from the 1950s—a dapper man who looked like an older, more chiseled version of Buddy Holly, sporting black horn-rimmed glasses and a sharp single-breasted suit. He possessed a staggering intellect and a formidable skill set, and it’s hard to envisage many of Cage’s most famous works without him. In the 1960s, Tudor transformed from being a standout interpreter of other people’s compositions to being a composer of his own live electronic music. He largely stopped working directly with Cage, but maintained a decades-long collaboration with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company.

Tudor rarely granted interviews, and generally avoided talking at length about his methods. When he did speak, he was brief and candid—even blunt. Nakai includes an anecdote from the composer Christian Wolff, who recounted Tudor’s fighting words to Theodor Adorno at Darmstadt in 1961. After Adorno gave an intricate, scholarly disquisition following a performance of Cage’s “Cartridge Music,” Tudor said to the famed thinker, “You haven’t understood a thing.”

David Tudor, X1000 amplifier kit [0188], ca. 1966. Courtesy World Instrument Collection, Wesleyan University. Photo: You Nakai. All rights reserved.

As the 1960s progressed, Tudor continued going against the grain. He disliked the synthesizers that were coming into vogue, preferring instead to build many of his own electronic instruments—small, homemade sound-making devices. (This, in turn, enlarged Tudor’s already potent aura of mystery—it was often hard to discern exactly what these homebrew circuits were, and how they worked.) He was a pioneer of what would now be called “sound art,” creating several groundbreaking sound and multimedia installations—most famously Rainforest (1968), an iteration of which is in the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection—and rewiring preconceived notions about composition and performance. “I don’t like to tell the machines what to do,” Tudor once said. Instead of specifying a composition from the top down, he created conditions by which interesting sounds could be made in a real-time, bottom-up process. In Rainforest, transducers attached to resonating objects generate a strange and beautiful sort of music.

Tudor may have been cryptic, but he left behind a lot of clues prior to his death in 1996 at the age of seventy. His paper archives are housed at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles—a voluminous stockpile, containing everything from receipts to circuit schematics to recipes to clippings from magazines. These archives formed the primary fodder for Nakai’s book. Over hundreds of painstaking pages, Nakai slowly pieces together a biography through a deep dive into these archives. It wasn’t an easy process, because the archives are not only a disparate assemblage, but also fairly abstruse. The circuit schematics, for instance, are often not the standard diagrams used by engineers, but semi-inscrutable, seemingly by design.

Re-drawing of Tudor’s matrix map (list of inputs and outputs to matrix switchers and mixers), in the form of a connection diagram, for Hedgehog, 1985. Created by You Nakai. All rights reserved.

Nakai combines this archival research with new interviews with some of Tudor’s collaborators, including the composers Gordon Mumma and John Driscoll. He also explores another important archive—a collection of Tudor’s homemade electronic instruments that is stored at Wesleyan University—building on the extensive work done by other Tudor scholars, including Matthew Rogalsky and Ron Kuivila.

Nakai comes across in this book as earnest, humble, and eager to learn. His attention to detail is unflagging. In several lengthy passages, he meticulously goes through Tudor’s old clippings from hobbyist magazines and matches them to electronic instruments that Tudor constructed. It turns out that he often built his instruments based on do-it-yourself articles he found in mainstream magazines of the time, such as Popular Electronics. Sometimes the advice in these articles was followed to the letter; often, Tudor would modify the devices in interesting ways. For instance, Nakai writes, Tudor took creative license while building an audio multicoupler from the directions in an article in a 1970 issue of Popular Electronics, adding more inputs, outputs, and gain controls, and putting two circuits in one enclosure to make a “dual instrument.”

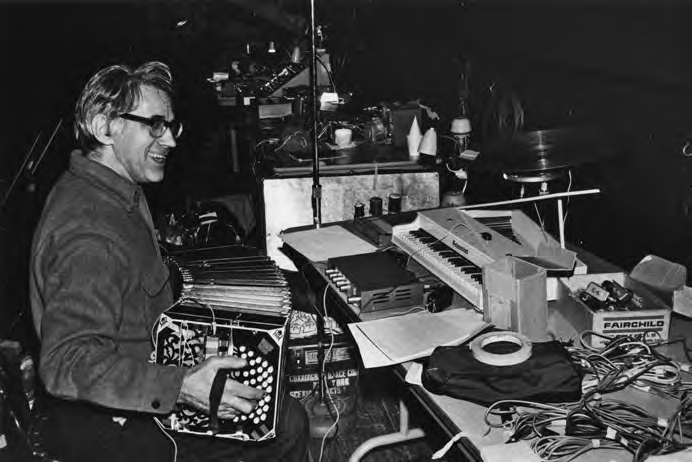

David Tudor rehearsing Bandoneon Factorial at the Berkeley School, September 10–11, 1966. Courtesy Klüver / Martin Archive & Experiments in Art and Technology. Photo: Franny Breer. All rights reserved.

Throughout the book, Nakai demystifies Tudor and his process. Electronic music of the past is often portrayed in a dreamy, magical light—a hazy historical landscape filled with misty, otherworldly sounds. But while the music of a bygone era may seem ineffable, it is not inaccessible. Listening to it can be a glorious and transcendent experience, but its inner workings can be made legible. Writers, historians, and researchers can help make those sounds understandable to the wider audience by exploring hidden meanings and developing a vocabulary to explain them more fully. Making the past legible empowers us. These composers weren’t perfect, omniscient geniuses. While there will never be another David Tudor, shedding light on his creative process makes one think, “Maybe I could do something like that, too.”

David Tudor performing the bandoneon, Brooklyn Academy of Music, February 1972. Courtesy James Klosty. Photo: James Klosty. All rights reserved.

While reading Nakai’s revelatory investigation—with his accounts of Tudor’s shop receipts and cutouts from magazines—one realizes that, for all of Tudor’s myriad talents, he was just human. He was trying to figure things out, to go his own way—always curious, always learning, surrounded and helped by brilliant collaborators and friends. His work is still astonishing and relevant today, in part because the pieces he created are still charged with life—unfixed in time, always moving and evolving.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.