A. S. Hamrah

A. S. Hamrah

In Melvin Van Peebles’s first film, the Nouvelle Vague meets the

Black diaspora.

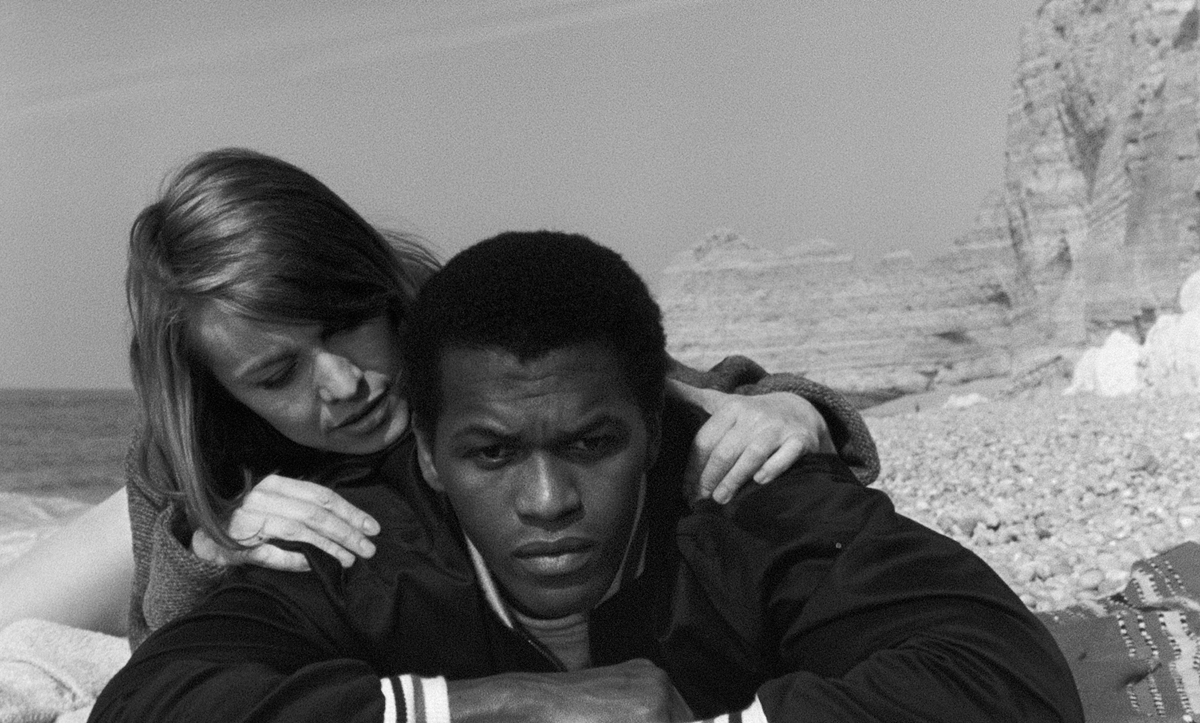

Nicole Berger as Miriam and Harry Baird as Turner in The Story of a Three Day Pass. Courtesy Janus Films.

The Story of a Three Day Pass, written and directed by Melvin Van Peebles, at Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City, and in its virtual theater, through May 13, 2021

• • •

Melvin Van Peebles, the provocateur, satirist, and revolutionary writer-director credited with inventing the blaxploitation film with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song in 1971, was born in Chicago in 1932. He made his feature-film debut, however, in France, in 1968. Like other Black writers from the US, including James Baldwin and Chester Himes, Van Peebles had left his home country for the more hospitable environment of Europe. By the early 1960s he had found his way to Paris. Van Peebles based The Story of a Three Day Pass, a sometimes tender and very hip interracial romance, on a novel he had written there, La permission, drawing on his experiences in the US Air Force.

Shot in black-and-white in 1966, just before President Charles De Gaulle withdrew France from NATO’s military structure and closed US military bases, the film is a portrait not just of a man and a woman falling in love but also of the American military overseas in the 1960s. The Story of a Three Day Pass shares Mickey Baker, of the R & B duo Mickey & Sylvia, with Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculine Feminine, shot in Paris around the same time, and it bears comparison to that film’s anti-American, anti-military scenes as much as to its use of the pop music of the time.

In Godard’s movie, French twentysomethings deface the walls of the US embassy with anti-American graffiti and shout against the Vietnam War. In The Story of a Three Day Pass, a lone Black soldier, Turner (Harry Baird), wanders uncertainly through the same Paris as Godard’s “children of Marx and Coca-Cola,” looking for love the same way, but with a distinctly different point-of-view. Vietnam is not even mentioned in The Story of a Three Day Pass.

Harry Baird as Turner in The Story of a Three Day Pass. Courtesy Janus Films.

Which is not to say that Van Peebles’s film is pro-military or pro-America. This is a portrait of the military from the inside, concentrating on one soldier as he puts up with and tries to ignore the idiotic white authority figures and fellow-soldier snitches who control his life, including his sex life. When Turner and his white lover, Miriam (Nicole Berger), a Frenchwoman he meets his first night on leave, dine the next evening in a Spanish boîte in Normandy, a flamenco guitarist dedicates a song to the couple using a racist term. Turner explodes in rage, beating the musician until he is pulled off and dragged from the restaurant. It is difficult not to see in his violent actions a Black man misdirecting his frustration with his commanders and his country onto this stranger for his clueless racism. But in attacking him, Turner is also acting like a soldier in an occupying army.

It’s not just Turner’s frustrations that Van Peebles dramatizes here but also his anxiety about being with Miriam. Sex and violence under the regime of racism is Van Peebles’s great theme, and while that comes to the fore in The Story of a Three Day Pass, it shows up in unexpected bursts, not in the sustained fugues of his next two films, Watermelon Man (1970) and Sweet Sweetback. Van Peebles places his abiding subject inside a more universalized story, that of delicate, sometimes awkward romance between a man on leave in a foreign country and a woman who doesn’t quite speak his language. At every opportunity, however, Van Peebles ironizes this basic setup, bringing it back to race, the obvious fact the film can’t escape even if these two lovers ignore it on the surface.

Nicole Berger as Miriam and Harry Baird as Turner in The Story of a Three Day Pass. Courtesy Janus Films.

When Van Peebles shows their reveries of each other before their first night together in a seaside pension, he has Turner imagining himself as a foppish lord in a Regency drama, with Miriam his fair lady waiting to be deflowered. Miriam, in her fantasy, sees herself in a tattered white slip, chased through the jungle by savage African natives and rescued by Turner, their chieftain with a bone in his hair. Van Peebles has always prided himself on being blunt and saying things that other filmmakers refused to say or even acknowledge. In this debut feature, he makes that stance witty by pointing to the naive pseudosophistication of not only the two lovers but also the kind of French film they might think they’re in.

Van Peebles’s candor is gentler in The Story of a Three Day Pass, without the crazed, brilliant rancor of the films he directed when he returned to America. His evocation of Miriam’s racist European imagining is unexpected in a seriocomic and stylish romance. But if in this story her crude fantasizing is somehow forgivable because she’s guileless and caring, that doesn’t translate to the USA. In Watermelon Man, when a white European sleeps with a Black American, she does it just because he’s Black, and Van Peebles excoriates her in no uncertain terms. Called out for her exoticizing, she immediately cries rape.

Nicole Berger as Miriam and Harry Baird as Turner in The Story of a Three Day Pass. Courtesy Janus Films.

The Story of a Three Day Pass is suffused with the style and techniques of the Nouvelle Vague: jump cuts, freeze frames, interior monologues, long takes and pans, city wanderings shot from the windows of buildings across the street, café and nightclub scenes, car rides out of town. As such, it is a late New Wave film, part of the second wave of freewheeling, youthful cinema that spread across Europe and the world after François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Godard’s Breathless came out in 1959 and 1960, respectively.

Beyond that, it has a special place among 1960s movies—it is neither American nor French, but a unique example of filmmaking from the Black diaspora, with a particular, even fragile viewpoint and artistry that were not seen again from Van Peebles after he returned to the country where he was born. It is without question recognizably a work of his, but it is thoroughly distinct, too. The Story of a Three Day Pass stands on its merits as an excellent film, and would do so if Van Peebles had never made another movie. One of the best of its time, it can take its place alongside other great black-and-white originals made by American directors that also came out in 1968, John Cassavetes’s Faces and George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead.

Harry Baird as Turner in The Story of a Three Day Pass. Courtesy Janus Films.

When Baird, as Turner, transforms himself in his barracks from soldier to civilian ready to hit the town, donning a plaid jacket, a shirt with a button-down collar, a skinny tie, a raincoat, and a pair of Ray Charles sunglasses, we witness not just an actor getting dressed up to go out, but a filmmaker announcing his arrival in the city of cinema. Almost the first thing this American in Paris sees when he gets to the capital is a movie poster being taken down, maybe so that the poster for the film he’s in can be put up in its place. In a 2012 interview with Miriam Bale in the L Magazine, Van Peebles said he was not imitating the French filmmaking of the time when he made The Story of a Three Day Pass. “I don’t know what a New Wave style is,” he claimed. “That’s some shit.” Maybe. But as Jacques Rivette once wrote, describing the genius of a different filmmaker, “the evidence is on the screen.”

A. S. Hamrah is the author of The Earth Dies Streaming: Film Writing: 2002–2018 (n+1 books) and the film critic at the Baffler.