Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

At Tate Modern, the art of the din.

Takis, installation view. Photo: Tate Photography (Mark Heathcote).

Takis, Tate Modern, London, England, through October 27, 2019

• • •

In the emerging history of sound art, Takis’s name often goes unmentioned. Takis, the alias of the Greek artist Panayiotis Vassilakis, who died in August at the age of ninety-three, was best known as a pioneer of kinetic sculpture. He is also remembered as an activist who advocated for the rights of artists. In 1969, Takis helped catalyze the formation of the Art Workers Coalition, a collective of artists, writers, filmmakers, and others who challenged the power of large institutions. He removed his Tele-sculpture from the Museum of Modern Art’s now-legendary The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age exhibition, arguing that he had not been consulted about the work (which is in MoMA’s permanent collection) being included. This defiant action, he hoped, would “be just the first in a series of acts against the stagnant policies of art museums all over the world.” Takis’s legacy in these categories is now in the history books, but his sustained and substantial work with sound, beginning in the 1960s, is less well-known.

Photograph of Takis and Guy Brett, 1966. © Clay Perry, England & Co. Gallery.

Takis moved from Athens to Paris in 1954, where he befriended Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely, Alberto Giacometti, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Brion Gysin, and Marcel Duchamp, among others. He started out making tall, wiry iron sculptures reminiscent of Giacometti’s bronze figures. He then massively expanded his reach, investigating magnetism, sound, and cosmic energies in a profound body of work that spanned seven decades. He moved in the 1960s to the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT, and then to New York, and eventually back to Athens. He attracted the attention of prominent musicians like John Lennon, who collected his work; William S. Burroughs wrote, in a long, zigzag ode: “You can hear metal think in the electromagnetic fields of Takis sculpture.”

Takis, installation view. Photo: Tate Photography (Mark Heathcote).

An intermittent din fills the sprawling and revelatory Takis retrospective currently on view at Tate Modern. A massive gong crashes every fifteen minutes, powerfully reverberating in one room. Piano and guitar strings, stripped of their respective instruments, are hit in jagged patterns by needles swinging like pendulums in another room. The controlled chaos of flashing electrical bulbs, quivering antennae, and slow-moving metal spheres from various Takis installations and sculptures adds a strange rhythmic pulse to the exhibition. You feel, almost, as if the pieces were alive.

Takis, Signal (detail), 1964–65. Steel, lamp, paint, 100.8 × 10 × 7.7 inches. © ADAGP and DACS, 2019. Photo: © Tate (Andrew Dunkley and Mark Heathcote).

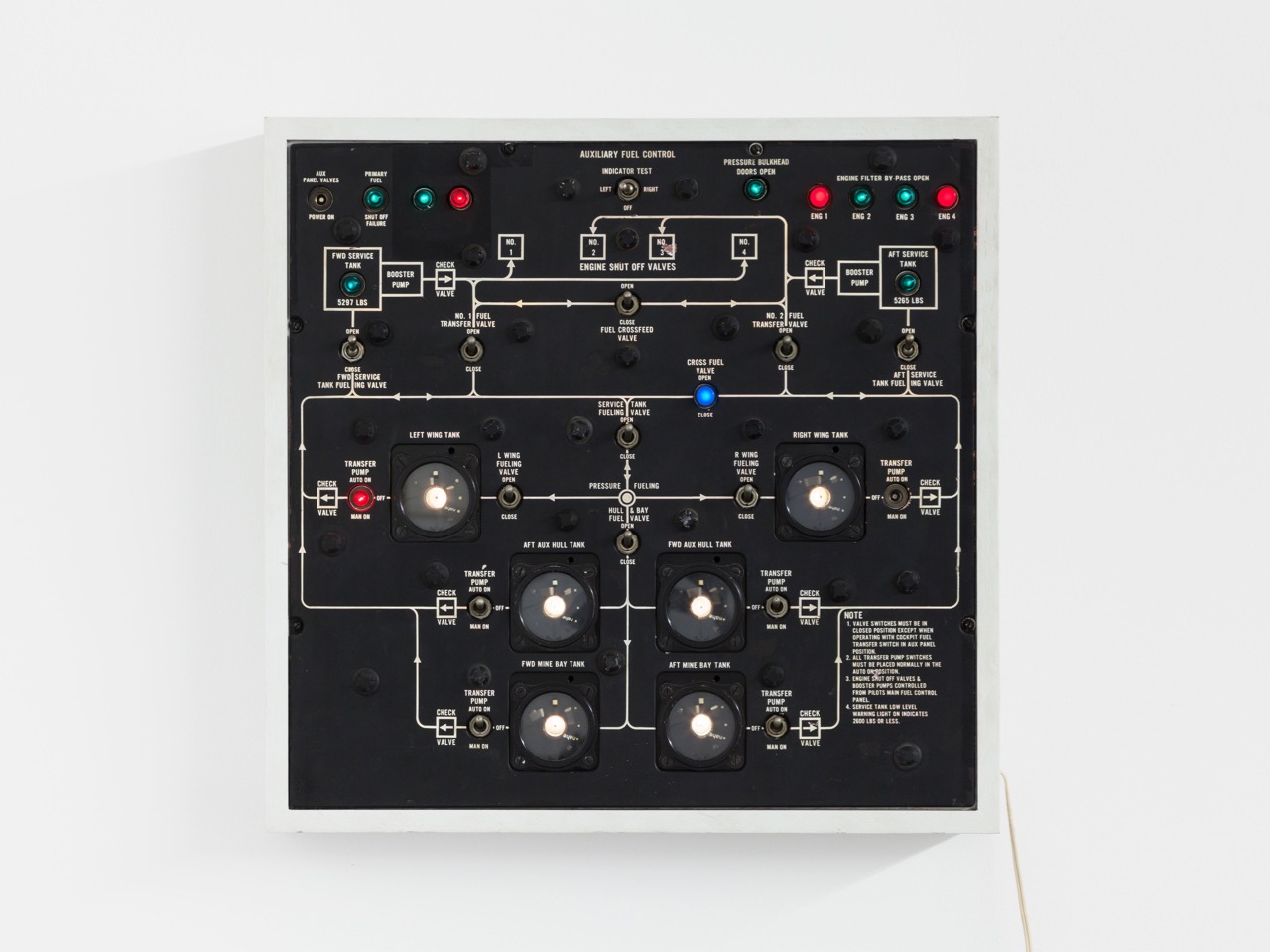

In a way, the pieces are alive, animated by electricity, or by the invisible forces of magnetism, or by equally invisible audio signals. Sound is a core component of many of Takis’s sculptures, even when it isn’t immediately palpable. Like the early electronic music composers in the 1950s, many of whom built or hacked their own custom creations, Takis culled many of his materials—switches, motors, electrical wiring, iron—from military surplus junk and from radio shops. In Signals, a series of sculptures begun in 1955 that sprout from the ground like spiky metal bouquets, the delicately trembling rods have a complex sonic ancestry: many of them were originally radio antennae from military vehicles. Black Panel Dials (1968) resembles the front of a modular synthesizer, with a cool array of flashing lights, but it was repurposed from sinister wartime technology (a helpful placard states that the piece contains radium, but that it is entirely harmless).

Takis, Black Panel Dials, 1968. Dials, lightbulbs, metal, paint, wood, 20 × 19.5 × 3.5 inches. © ADAGP and DACS, 2019.

Across the room, there is the low-level hum of lights slowly turning on and off in small electrical sculptures. They are not just any lights, but vintage mercury vapor lamps, glowing a softly opalescent blue. Takis grew up in Athens at a time, he said, when there was only one traffic light. When he traveled from London to Paris, he was bewildered by the train stations, calling them a “forest of signals.” “Monster-eyes went on and off, rails, tunnels, a jungle of iron,” Tate Modern curator Michael Wellen quotes Takis’s memoir Estafilades in an essay, documenting a key turning point in the Takis mythos. “I got out a chalk, and drew it all on the cement. I drew all those phenomena . . . We have chased the sacred symbols into the desert and replaced them with electronic eyes.”

Takis, Télélumière No. 4 (detail), 1963–64. Iron machine parts, light bulbs, wood, brass, steel, electromagnet, string, and paint, approx. 42.5 × 11.8 × 12.6 inches, 11.8 x 23.6 inches. © ADAGP and DACS, 2019. Photo: © Tate (Andrew Dunkley and Mark Heathcote).

Takis began experimenting with sound in many of his sculptures after partnering with the composer Earle Brown on an installation called Sound of Void, which was shown in 1964 in New York. He later collaborated on performances with the composer Charlemagne Palestine, the musician Joëlle Léandre, and the artist Nam June Paik. Takis’s sound pieces are known collectively as “musicals” (though none of them are musical in any conventional sense of the word). They are not composed, but use chance, often moderated via cleverly magnetized objects that move in such a way that they create sounds on their own. In an interview with the critic Maïten Bouisset, Takis talked about John Cage’s impact on his work. “John Cage composes like a musician, even in his incidental sounds,” Takis said. “In contrast, I don’t even know the musical alphabet . . . we do exchange ideas. He’s interested in the type of dry, high-pitched sounds that I happen to produce but he doesn’t appreciate more melodious sounds. He believes they don’t fit my approach. And I have enough admiration for him to follow his advice!”

A kind of alien dissonance is created as swinging objects hit strings, their resonances clashing and strangely intermingling in their slow decay. Like Alvin Lucier, Takis delved deeply into the physical properties of acoustics, but instead of writing compositions, he crafted solid forms that made sonic mysteries, and the force fields surrounding us, visible to the naked eye.

Takis, Musical Sphere, 1985. Aluminum, iron, metal string, metal wire, paint, polyester, 63 × 39.4 × 44.9 inches. © ADAGP and DACS, 2019. Photo: Hlias Nak.

“Music has always played a very important role in my life,” Takis said. “The idea of capturing the music of the spheres was linked to my personal history, and my intention was to make nature’s phenomena emerge from my work. Yet in nature everything is sound: the wind, the sea, the humming of insects.”

Everything is sound: in Takis’s work, sound emanates as a natural force, joined with the secret lines of magnetism, the laws of physics. It extends far beyond the hard rules of science, or the mercurial whims of humans, emerging as art that is universal and transcendental.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.