Mark Dery

Mark Dery

Decadence and decay, freedom and friends: Peter Hujar’s 1976 photo book captures the utopia of dystopia.

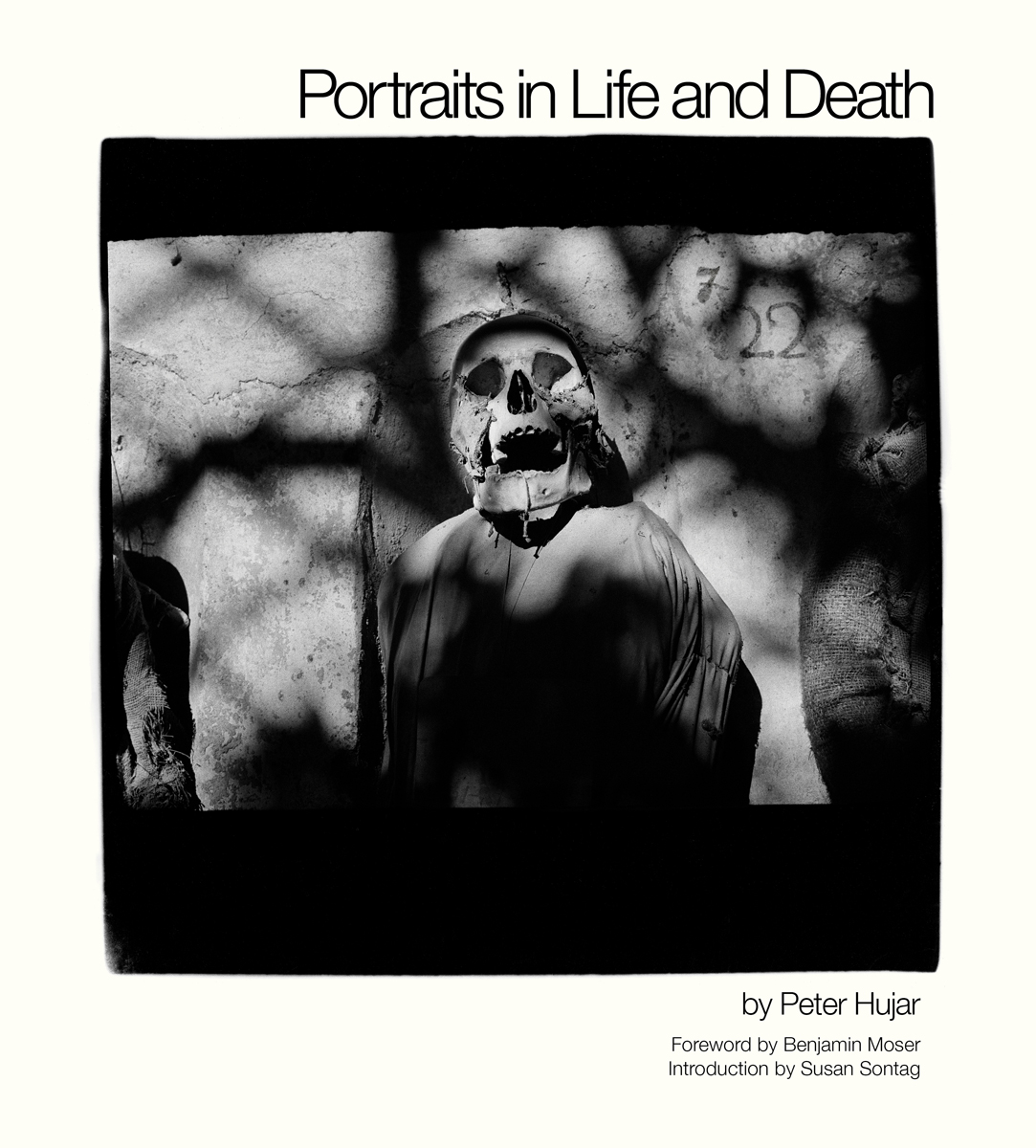

Portraits in Life and Death, by Peter Hujar, foreword by Benjamin Moser, introduction by Susan Sontag, Liveright, 100 pages, $75

• • •

Portraits in Life and Death is the only book Peter Hujar published in his lifetime. A slim collection of black-and-white photographs of the mostly gay anti-society of ’70s New York (Susan Sontag, John Ashbery, William S. Burroughs, Fran Lebowitz, Robert Wilson, Divine, and Hujar himself, among others), it went virtually unnoticed by critics when it appeared in 1976, despite an introduction by Sontag, and was almost immediately consigned to the remainder bins. In the decades since Hujar’s death (from AIDS-related pneumonia, at fifty-three, in 1987), it has acquired cult status, confirming him as the Nadar of the downtown demimonde. Now, it’s been reprinted for the first time by Liveright with Sontag’s original introduction and a foreword by the translator, essayist, and Sontag biographer Benjamin Moser.

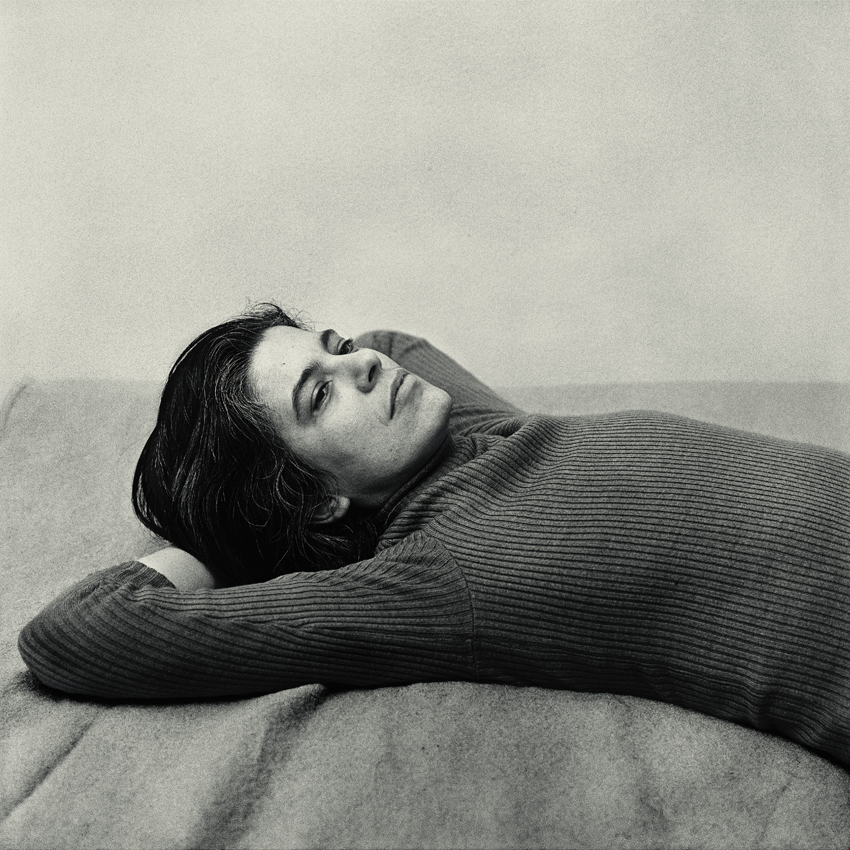

Susan Sontag. From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Portraits in Life and Death conjures a lost New York, before its gay bohemia and artistic vanguard were decimated by AIDS and, after the Trump ’80s made the city safe for hedge-fund managers and Abu Dhabi princelings, by gentrification. This was the decaying, dysfunctional, crime-ridden, near-bankrupt New York immortalized in the Daily News headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead” when the president nixed the idea of a federal bailout for NYC during its 1975 fiscal crisis; the New York of the July 13, 1977 blackout, which plunged most of the city into darkness and resulted in widespread looting.

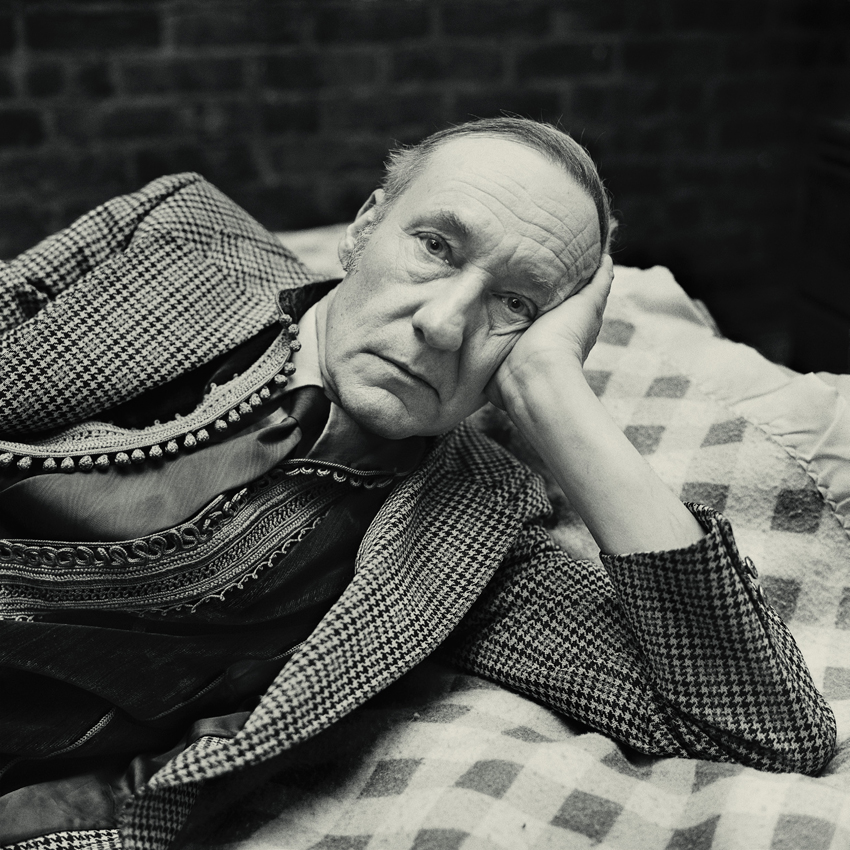

William S. Burroughs. From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

But it was also the New York of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, CBGB and the Village Voice; a Burroughsian interzone recalled by Lucy Sante in her essay “My Lost City” as “a free city, like one of those pre-war nests of intrigue and licentiousness where exiles and lamsters and refugees found shelter in a tangle of improbable juxtapositions”—bohemia’s last redoubt, “with no shopping malls, few major chains, very few born-again Christians who had not been sent there on a mission, no golf courses, no subdivisions.” The very name inspired a shudder of revulsion in Middle America, which made New York a mecca for bohos, weirdos, would-be Warhol superstars, Lou Reed epigones, and queer folk like Hujar. This is the New York of Portraits in Life and Death: a utopian dystopia; a rotting necropolis alive with underground hustle and bustle (mostly hustle).

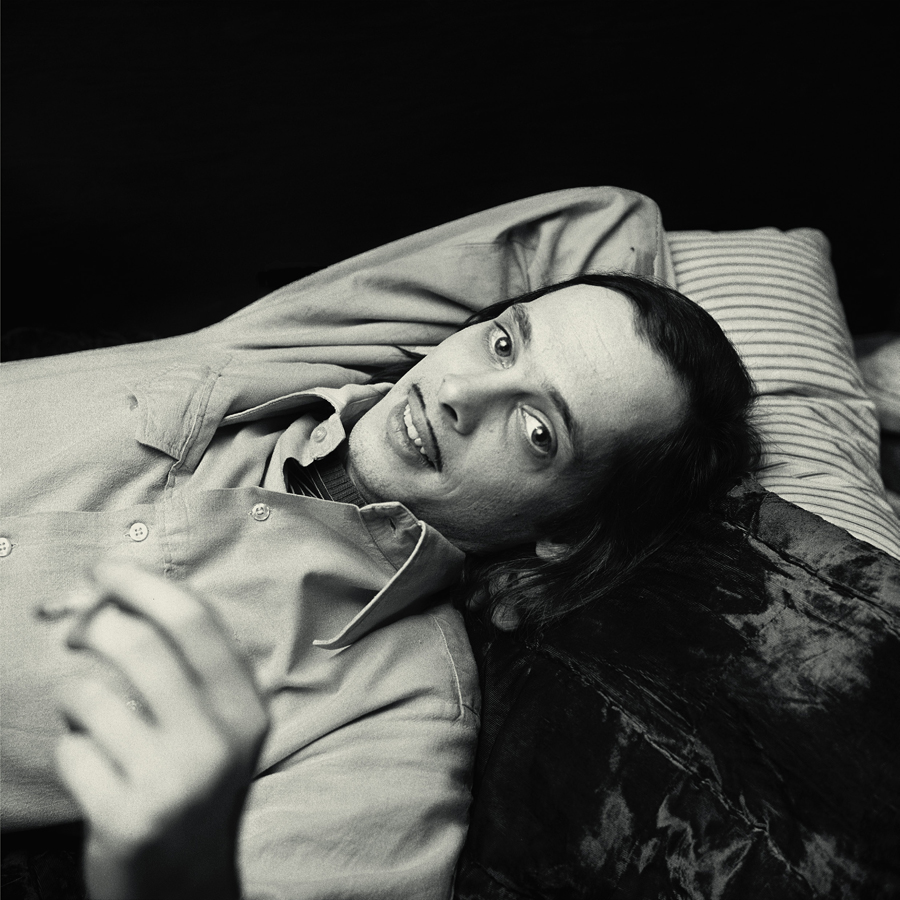

John Waters. From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

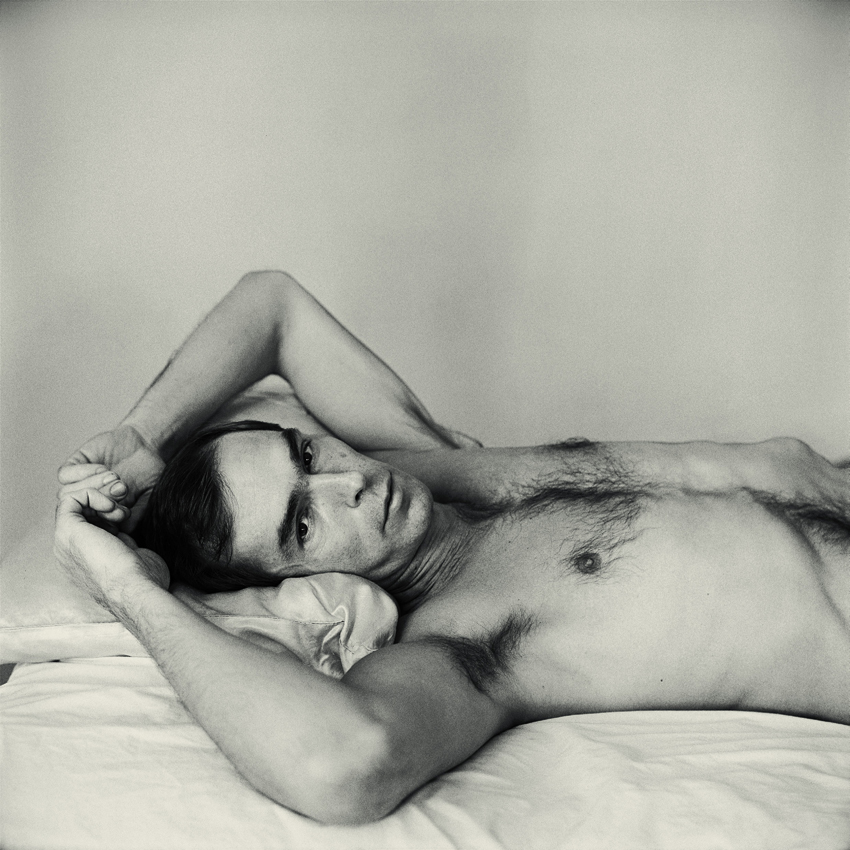

Hujar’s subjects meet our gaze across a gulf of irony, caginess, or alienation—but always with “blistering, blazing honesty directed towards the lens,” as one of his sitters put it. “That’s what Peter wanted and that was his great, great talent and skill.” The photography critic Vince Aletti regards us with the cool insolence of New York affect. A startlingly young John Waters, already sporting his pencil mustache (but not yet the smutty-uncle smirk we know and love), gives us a knowing look. T.C., about whom nothing is known beyond the fact that she may have stripped for a living, peers languorously back through slitted eyes, lazing naked in bed. There are exceptions: a few, like the drag queen Divine (star of Waters’s gleefully gross Pink Flamingos), stare abstractedly into nowhere, at nothing, as if seeing something we can’t see. Some, like the dance critic Edwin Denby, assume the aspect, eyes closed, of the deceased they one day will be, and in many cases now are, for most of them are dead, at least five of them from AIDS-related illnesses.

Divine. From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

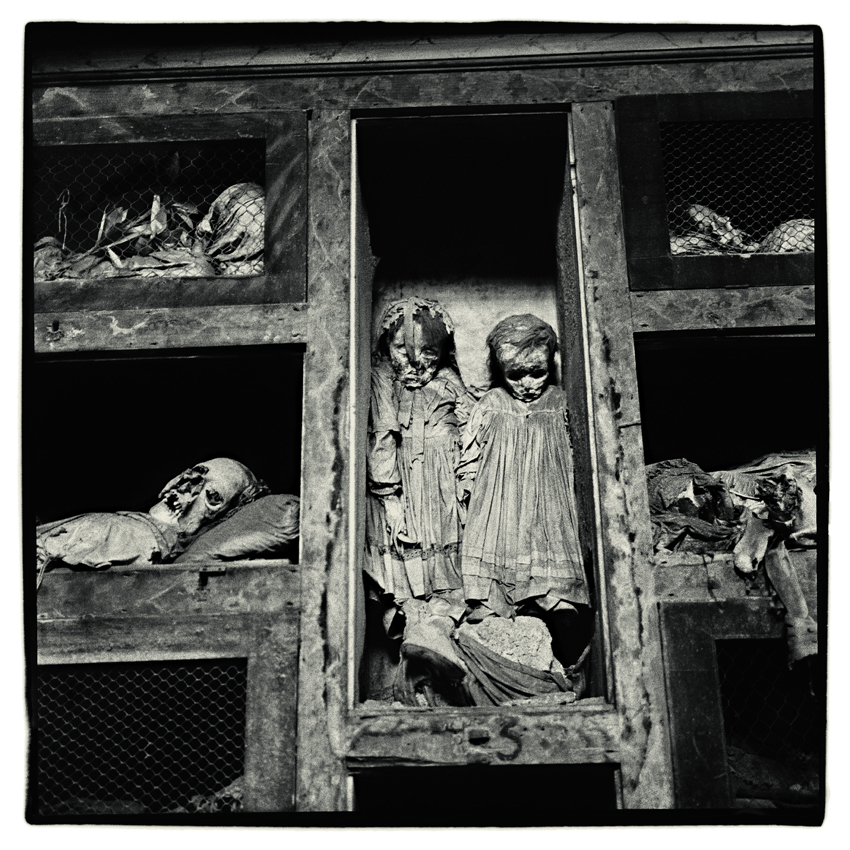

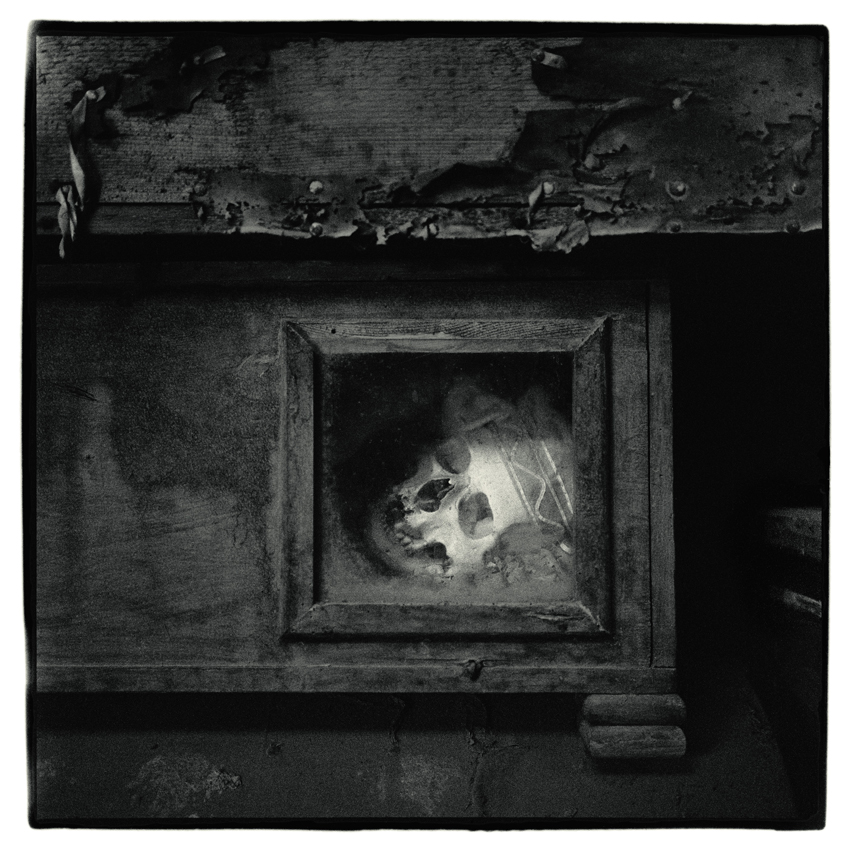

Not so much a tableau vivant as a tableau mourant, Hujar’s collective portrait of the downtown scene catches it in its glitter-and-doom, Weimar-Berlin last days, unknowingly poised on the cusp of the Reagan era and the “Black Angel’s Death Song” of AIDS (to borrow a Lou Reed lyric). Hujar invokes the skull beneath the skin through the black magic of photography, which, by fixing his subjects’ expressions for eternity, turns living faces into death masks and, contrariwise, brings the dead to life by putting flesh on the bones of memory. Then, in a memento mori, he pairs their portraits with photos of mummies and skeletons in the catacombs of Palermo, Italy: a skull crowned by white fabric roses; a mummified child sleeping away the centuries in her tasseled nightcap; a cleric straight out of a Francis Bacon painting, dark sockets staring eyelessly into eternity, toothless mouth yawning in a silent scream.

From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Shot against a white wall, the artist Paul Thek, one of Hujar’s lovers, seems to regard us from the void, as if he’s already crossed over. He transfixes us with a stare that is somehow unseeing yet all-seeing. His mouth is ajar, which professional overinterpreters (in other words, critics—like this one) might read as a premonition of the artist David Wojnarowicz’s deathbed photo of Hujar, mouth agape. Like Hujar, Thek believed, as Oscar Wilde did, that “the true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible”; reducing the beheld world to a veil between us and the “real” meaning of things profanes that mystery. Wearied by Sontag’s insistently cerebral pontifications about art, he interrupted, “Susan, stop, stop. I’m against interpretation. We don’t look at art when we interpret it.” Point taken, she dedicated her 1966 essay collection Against Interpretation to Thek.

Paul Thek. From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Hujar’s portraits reveal the mystery of the visible. Against the grain of our time, when the “hermeneutics of suspicion” (Paul Ricœur) mandates that we view every text as a mask concealing nefarious politics or moral depravity (Roman Polanski, Pablo Picasso, Woody Allen, Carl Andre, Roald Dahl), Hujar insists on the eros of looking. He wants us to look at art, not through it; to let its phenomenological impact rock us back on our heels. “The sight of naked flesh for me is like a physical blow,” he said. Which isn’t to say that he denies the depth of things, just that he refuses to privilege the act of reading over looking, subtext over surface.

From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

“I make uncomplicated, direct photographs of complicated and difficult subjects,” he said. “I photograph those who push themselves to any extreme and people who cling to the freedom to be themselves.” If the subjects of Portraits in Life and Death have one thing in common, it’s their defiant selfhood, their categoric refusal to be anyone but who they are. He chose people with “a certain kind of isolation built into their personalities,” a friend recalled; people who, despite (and because of) that alienation, were drawn to New York in search of an imagined community of others like them, others who’d always felt Othered.

Peter Hujar. From Portraits in Life and Death. Courtesy Peter Hujar Archive, LLC / Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Hujar—whose childhood was “worse than Dickensian” in its misery (Fran Lebowitz); who, according to the Wojnarowicz biographer Cynthia Carr, “left home while he was still in high school on the night his mother threw a bottle of beer at his head”; whose mother didn’t visit him, not even once, when he was sick with the disease that would kill him—knew that feeling. He dreamed of a surrogate family, says Carr, a “tribe” of outsiders who “shared his ideas about life.” Portraits is a family album for the disowned.

It’s also a Manhattan Death Trip, a collection of postmortem photographs drawn, paradoxically, from life. “Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death,” observed Sontag in the introduction she wrote in a hospital bed the day before “the first of the surgeries for the cancer whose sequels, thirty years later, would kill her,” writes Moser. “In the midst of life, we are in death,” the Book of Common Prayer reminds us. But on we go, hurtling toward our finitude at the speed of life.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and the author of four books, most recently, the biography Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. He has taught journalism at NYU and “dark aesthetics” at the Yale School of Art; been a Chancellor’s Distinguished Fellow at UC Irvine, a Visiting Scholar at the American Academy in Rome, and a fellow at Hawthornden Castle near Edinburgh; and published in a wide range of publications.