Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Art by and for the people vs. architecture in the service of empire.

Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City, by Rafael Schacter, MIT Press, 386 pages, $39.95

• • •

It is appropriate for this moment in history, when millions are being immobilized by a thousand cuts of an expansionist empire, that Rafael Schacter’s Monumental Graffiti uses destruction as one of its themes and runs it through the filter of Britain, cradle of imperial dementia. Schacter’s heavy and exuberant academic book traces the line of graffiti, using “public space” as the frame (literally), balancing the individual acts of graffiti writers and other public-space remodelers against the monuments and official totems of colonization that tag spaces you might otherwise think belonged to the people.

Edwin, WHEN I GROW UP I WANT TO BE AN APARTMENT BLOCK, 2022. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy the artist @thelazyedwin.

As Schacter puts it, “while staticity reigns for the institutional monument, in graffiti a culture of destruction rather than protection rules.” “Protection” and “destruction” here are fluid terms. Schacter quotes from 2021 guidelines to remove and prevent graffiti that were issued by Historic England, an advisory body to the UK government, which claims that graffiti creates “an atmosphere of ‘lawlessness’ in which crime and anti-social behaviour can thrive.” In the battle between graffiti and Britain’s “heritage regime,” which acts end up feeling most criminal? For example, the upkeep of London’s “comedically high” 169-foot-tall monument to Horatio Nelson—“over double the height of the largest known ancient column”—involves “re-lacquering of the acanthus leaves; as well as the re-patination and hot-waxing of the bas-reliefs and Landseer lions.” How many Londoners are happy to see that activity funded? And that’s not where the spending stops—any graffiti on this monument will be removed with one of these official methods: “mechanical, water, chemical and laser,” perversely the remit of a “conservation team.” I have been haunted by this Schacter formulation for months: the “artifactual preservation of our official (or institutional) heritage and artificial destruction of our unofficial (or independent) one thus proceed hand in hand.”

MOSA, Untitled, 2022. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy the artist and Tramontana Magazine. Photo: Elliot Sitbon.

I will speculate that even imperial fans of Nelson would not likely posit that he is telling us anything novel, while every scratch of graffiti on his base is precisely that—the newly rendered marks of a living human. If this were the only perspectival shift in the Schacter book, it would be worthy of our time. How odd is it that our public spaces and our tax funds are given over to statues of people we know nothing of, or loathe?

REMIO, Sao Paolo, 2009. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy the artist.

Aside from parks with high tourist pass-through (like Central Park), interstitial urban spaces that were once more hospitable to workers now have fewer trees and more anti-homeless benches. Government and corporations provide public space in name only when it is, materially, just a space for taxpayers to pass through on their way to point of consumption. The graffiti writer and public artist inverts this, registering to the state as “destruction,” while having absolutely no agenda other than the iteration of the artist’s individual spirit. The state, legion in its erasing agents, wants you to believe that graffiti is the tip of some spear coming to cleave your life, while the state goes ahead and upends your life with all of the latent malice it has isolated, split off, and projected onto the graffiti artist. No graf artists have ever made it harder for you to find a place to eat your lunch.

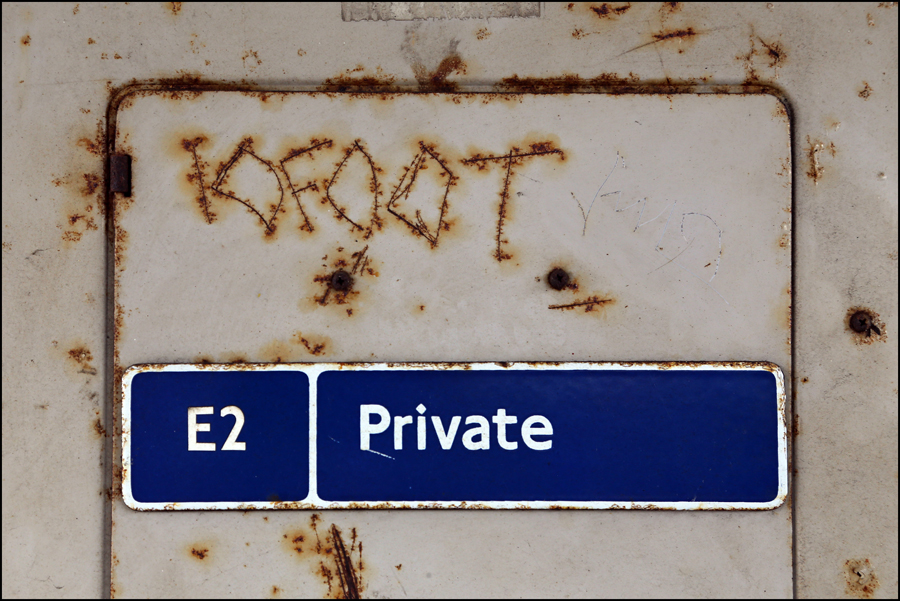

10FOOT, West London, 2018. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Photo: Alex Ellison.

Schacter addresses exactly this in his discussion of “atmospheric walls,” a concept he borrows from theorist Sara Ahmed, which he describes as “the intangible barriers that can obstruct just as powerfully as any material edifice.” His questions are much like mine: “Are there benches to sit on, places to play? Is the space free or (at least) affordable? Are we questioned or welcomed when entering these sites?” In his discussion of POPS (privately owned public spaces) in the UK, Schacter quotes an interview with a developer in Stratford City talking about a shopping center. Their stated goal was to “make sure it was up to the standard of any private office lobby.”

R Seventeen / sory.world, 10 FOOT ’22, 2022. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy the artists.

The proper responses here are not necessarily found in graffiti. If I came to this book originally more sympathetic to the kind of destruction familiar to me—say, the drippy acid tags and spray-can pieces of London writers like 10Foot—I am most excited now about artists who disrupt the public weave with interventions that bypass written language for visual work that returns us to the problem under our feet. Graffiti art was reborn in the ’70s in New York, when the lesser-known but increasingly popular artist Gordon Matta-Clark was also working. It pays to examine how these two strategies are being reconstituted now.

Enrique Escandell, Madrid Subway, 2015. Taken from Subterráneos by Enrique Escandell. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy the artist.

For graffiti, the biggest canvas for graf writers was a part of the infrastructure that moved around all through the city: the subways. In contrast, but also in concert, Matta-Clark used buildings that were abandoned or ignored and cut gorgeous half-moons and light shafts into and out of them. Now subways are built differently, and there is little abandoned real estate in heavily populated areas. So tactics have changed, and when there is even more money than ever flowing through all of these private office lobbies, artists adapt.

OX, Untitled, Paris, 2016. Acrylic on paper. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy artist.

Taking a page directly from Matta-Clark, Andrew Kass executed a gorgeous piece, which Schacter discusses, called A Little about Lots. In 2020, Kass found “a New York City lot left vacant for over two decades” in the Financial District. The corner site was separated by walls that were not atmospheric but also not that impressive—the plywood painted green that any New Yorker knows by heart. Kass cut “dramatic, curving arches” out of the plywood “to reveal a beautifully disheveled green space.” It apparently lasted only a week, which is roughly how long a lot of Matta-Clark pieces lasted in public before being dismantled.

EGS & TRAMA, Helsinki, 2019. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy the artist.

Kass’s piece recalls Eric Sanderson’s Mannahatta Project, which imagines how the city would look if the Lenape had never lost it to the Dutch, and also Christopher Harris’s slow and slower 2001 film, still/here, which captured St. Louis’s abandoned buildings (some of them pierced by tall growing wildness) in 16mm black and white. I love Schacter’s conclusion of Kass’s piece, that “what emerges here is thus not just a communicative and utopian rejection of the border but a practice in which turning the private into public is the rule.”

Escif, Untitled, Beirut, 2021. Acrylic paint on wall. From Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City. Courtesy the artist.

Take away the issue of graffiti and modern art and all the trappings that indicate gestures that some other person might kind of make, and consider the real issue from the putative “average taxpayer” angle. What could be more basic and urgent than reclaiming public space from militaristic and antihuman corporate control? Do you want to eat your burrito on a bench looking up at trees, or perched inside a Pret a Manger, staring at Nelson? What returns is a line from the late, great Fredric Jameson, because we are never really talking about benches or graffiti when we discuss what Jameson calls “this whole global, yet American, postmodern culture,” which he correctly characterizes as the “expression of a whole new wave of American military and economic domination throughout the world.” Every time a bench is studded with little metal lumps that make it antihuman, and every time the human trace is pressure-washed off a bollard that wasn’t saying anything anyway, it is joined in spirit to bunker busters being dropped on Beirut and Damascus and Gaza and Bint Jbeil. Jameson tells us, and which we must always remember, that “as throughout class history, the underside of culture is blood, torture, death and horror.”

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, was recently published by Semiotext(e).