Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

In Matthew Rice’s book-length poem, a portrait of the poet on a factory night shift.

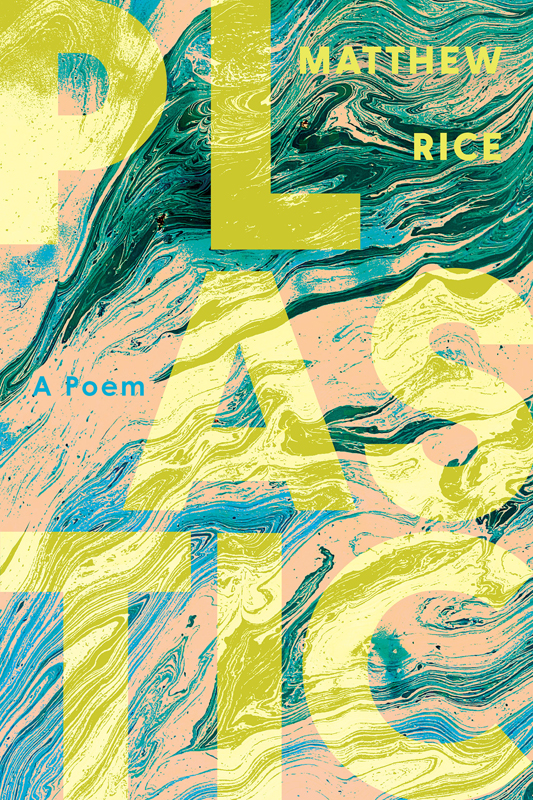

plastic: A Poem, by Matthew Rice,

Soft Skull, 90 pages, $15.95

• • •

Before it was a thing, before it was a noun, plastic was an adjective (see the plastic arts) meaning shaping or shaped, having the power to give form, or being formed in turn. (Henry James, in The Portrait of a Lady, notes the aesthete Rosier’s “fine sense of the plastic.”) Outside the realms of myth and religion, has a substance ever seemed so miraculous but abject, mundane and full of potential? Roland Barthes in Mythologies (1957) calls it a “disgraced” material: “lost between the effusiveness of rubber and the flat hardness of metal; it embodies none of the genuine produce of the mineral world: foam, fibres, strata.” In Alain Resnais’s short film Le chant du styrène (1958)—with poetic text by Raymond Queneau—plastic has arrived from a colorful future of both fantastic and natural forms, but the most extraordinary sight is its production: the fusion and transmutation of particles into something apparently infinite, creamily self-same and cheaply sensuous. Admired and despised at mid-century for its ubiquity, plastic is now of course the very image of poisonous insinuation and latency. Plastic becomes plastics and in turn microplastics, and those are never going away.

Let’s not stick too fast to etymologies and their movements, but plastic shares something with poesis: the poetic faculty as power of making and forming, manufacturing shape and style out of inchoate stuff. So plastic: A Poem is and is not a contrary title. In Matthew Rice’s furiously everyday and erudite book, all senses of plastic are in play, but this is first of all a (seemingly autobiographical) study of the rigors of work in a plastics factory in the poet’s native Northern Ireland. Specifically, working the night shift: the short sections or discrete fragments in plastic are precisely time-coded, but, aside from the rhythm of clocking on and off, the chosen moments appear haphazard, random way stations en route to morning. Time is a structure and a subject, an anxiety even while the poet-worker is asleep: “I wake at 3 a.m., the hour no one / wants. Really, it’s my heart that wakes me / beating its way out. . . . It’s Monday tomorrow, it always is when dreams are alarms.” Weeknights are epics of wakefulness, boredom, concentration, and occasional interludes of human connection with coworkers: “wee Gail” who has just turned seventy, “Joey the pigeon-racing fanatic” who wrings the neck of a panicked bird that’s snuck into the factory. On a break at 1:15 in the morning, Rice drives to a twenty-four-hour supermarket, where he wonders “for a moment if preservation means perishing in increments.”

In some ways, this portrait of factory life is very much of the twentieth century, or even the nineteenth, if you merely substituted the raw material. Rice’s workplace is filled with ancient technology: “The Bridgeport mill machine / from 1965 pools incontinent / around its base”—replacement parts can no longer be sourced; it’s like tending a senile relative. The streamlined Fordist dream (or nightmare) of serial production has curdled into clanking, sweating, leaking and lethal half-life. Or else it was always like that in any case, just as fantasies attaching to contemporary technology rely inevitably on laboring and suffering bodies—located elsewhere, if we are fortunate enough. plastic is news from this material other place that many of us need not think about. Not so for the factory-line worker. On a budget flight to Italy, Rice suddenly recognizes, because he made it himself, the “pristine edge” of his seat: “even on holiday, / even at thirty-five thousand feet, / at five hundred miles an hour, / you can’t escape.”

Can’t escape yourself, the selling of your labor, nor the systems that surround both. But also, surely: you cannot get away from forms, their ubiquity and the knowledge and skill that go into their making. plastic is a poem, or cycle of poems, that is keenly aware of its status as a made thing among others, an artifact of labor in language, thought, and feeling. It’s partially a matter of terminology, which is both generic and peculiar. “Every factory has the same lexicon: / cavity, barrel, latch, button, cycle, / part, material, scales, cutter,” and so on for another five lines of manufacturing terms—“which is to say my tongue / moves aimlessly in its mouth.” There are national differences in factory vocabulary that remind us this work is being done by specific bodies in a particular place and time: “The English call it shavings, / the Americans call it chips, / but Here we call it swarf, / the metal dust churned up / by the steel cutter.” (Swarf, it turns out, is also a verb meaning to stagger, swerve, or grow faint: apt word amid exhausting night-work.) In one of his most lexically adventurous moves, Rice composes part of plastic in “Eejıt”—a phonetic writing system for Belfast vernacular, invented by the poet Scott McKendry.

In plastic, Rice has also written a book brimming with allusions to other books—also movies, TV shows, childhood toys like his Evel Knievel figure that “smelt of nicotine.” There are recurring references to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a copy of which Rice has smuggled in to work like “contraband beneath / the frosted-out skylight.” The plastics factory is in the townland of Kilroot, where Jonathan Swift lived for two years in the 1690s, began his scabrous satire A Tale of a Tub, and (according to local legend), while observing the giant’s-face form of a cliff, first had the idea for Gulliver’s Travels. We learn this last bit of information in Rice’s notes to the book, which are both helpful and a likely wink to the famous notes to The Waste Land. Elsewhere, like T. S. Eliot’s poem, plastic bristles with pop-cultural detail: old Marvel comics, Gary Numan, Prometheus, AC/DC’s song “Hell’s Bells” (as used by British soldiers to keep prisoners awake in Afghanistan). In the end, it is also a poem about knowledge and art: the words and music and imagery that live alongside the night’s labor, that make it bearable and at the same time highlight its violence.

Brian Dillon’s memoir Ambivalence will be published in 2026 by New York Review Books and Fitzcarraldo Editions. He is working on Charisma, a novel.