Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Notable neighbors: Francesca Wade looks back at the lives of five

London women.

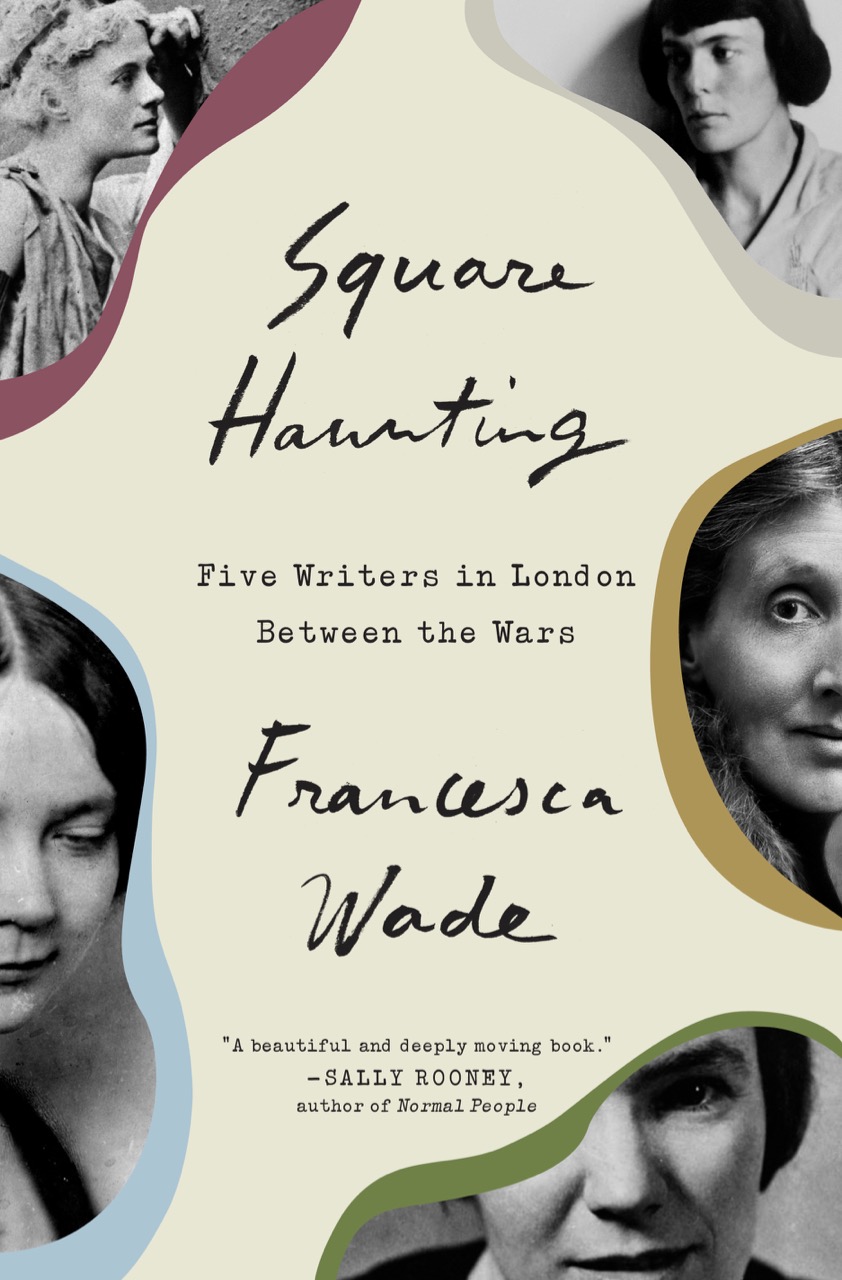

Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars, by Francesca Wade, Tim Duggan Books, 421 pages, $28.99

• • •

On the night of Tuesday, September 10, 1940, German bombers were aiming at King’s Cross station in central London when instead, and not for the first time, they hit the adjacent neighborhood of Bloomsbury. In the quiet early-nineteenth-century enclave of Mecklenburgh Square, six nurses from a nearby hospital were among the dead. A time bomb embedded itself in the square, so that when Virginia Woolf came up from the country on the eleventh, and tried to reach her flat at number thirty-seven, she was held back by air-raid wardens. From the corner of Doughty Street, Woolf could see that the former house of her friend Jane Harrison lay in ruins: “Scraps of cloth hanging to the bare walls at the side still standing. A looking glass I think swinging. Like a tooth knocked out—a clean cut.”

Square Haunting, Francesca Wade’s richly researched, elegantly written study of five women’s lives and works, starts here, with the explosive end of a historical era. Wade’s five subjects are Woolf, the classicist Harrison, poet and novelist H. D. (Hilda Doolittle), the detective novelist and Dante translator Dorothy L. Sayers, and historian Eileen Power—all of whom lived and worked in the square. Square Haunting is not a study of the overfamiliar Bloomsbury set, of which Elizabeth Hardwick once complained: “it wearies as an idea, a design, a gathering, and one would like to have each speckled specimen alone, singular.” Instead, Wade—who is editor of the London literary journal White Review—moves from the geographical and socially precise locus of Mecklenburgh Square to a glancing history of women’s creative, economic, and intimate lives in the early twentieth century.

When H. D. settled into Forty-Four Mecklenburgh Square in February 1916, the area was already home to many artistic and political radicals. A century earlier, the new squares of Bloomsbury were speculative developments meant to lure the wealthy eastward from Kensington and St. James. The plan failed; Bloomsbury became an “odious vulgar place” (as Thackeray put it) full of boarding houses, pubs and hotels, obscure lecture halls and meeting rooms for radical and émigré groups. It was also a place where women might live, single or attached, away from the rigors of respectability. H. D. was hoping to put behind her the dismal first years of the war: she suffered a stillbirth in 1915, and her husband, Richard Aldington, had dutifully gone to fulfill his part in a conflict she loathed. “All I want is to keep the home-fires of divine poesy humming till the boys come home!” When Aldington did come home, he commenced an affair with a neighbor, taking up with her just a thin partition away from the marital bed.

Wade is particularly good at conjuring, out of her subjects’ living arrangements both mundane and mad, an image of time, place, and creative milieu. As a young intellectual woman living in Mecklenburgh Square in the 1910s and 1920s, you could write all day at a desk overlooking the central garden, then spend your evening, as Sayers did, agog at the Grand Guignol theater, attending a basement meeting of some mystical cult, or gorging yourself at a cheap restaurant in Soho. You might wake to the sound of suffragettes scraping their burnt toast next door, or find that Ezra Pound had moved in across the hall, and would not stop bursting into your room to declaim his own verses. Most of the women in Wade’s book came to Bloomsbury to find their equivalent of Woolf’s “room of one’s own”—an idea that Harrison first bruited, in a lecture—but they also endured the attentions of a series of awful men. As H. D. and Sayers especially discovered, literary freedom still came with a certain personal price: at best a pestering Imagist, at worst abandonment with an illegitimate child.

The two academics in Square Haunting fared better on that front, though found a lot of male professors standing in the way of their professional advancement. Harrison is an amazing figure, hugely famous in her time for her daring and popular studies of ancient Greece, constantly attacked by colleagues and in the press for both her writings on primitive ritual and her campaigning to allow women into England’s universities. In her seventies, well ensconced at Cambridge, she suddenly quit her academic post and, in the company of poet Hope Mirrlees (possibly her lover), moved to Paris, then to Bloomsbury, where she learned Russian and spent her days with displaced European radicals. Equally well known in her lifetime was Power, who parlayed her pioneering research on medieval nunneries into a career on radio and friendships with the likes of Paul Robeson.

Inevitably, the presence of Woolf dominates the book, but Wade leaves her story till last so that we have already gained a detailed sense of a Bloomsbury culture that was not “Bloomsbury.” The writer and her husband Leonard had lived not far away, in Tavistock Square, but construction noise drove them out in August 1939. At Mecklenburgh Square, and sometimes at their house in Sussex, Woolf embarked on a biography of art critic Roger Fry, her own memoirs, a history of Britain told largely through the lives of women, and her final novel, Between the Acts. Only the first and last of these were finished, but it was an extraordinary late creative push—all done while knowing that she and Leonard were on the Nazis’ list of those to be purged after invasion. Woolf drowned herself in March 1941. Wade manages to tell the familiar narrative of her last months in a wholly new way: as an industrious coda not just to a life, but to a whole way of life that prewar Bloomsbury had made possible.

Mecklenburgh Square was rebuilt after the Blitz, but not the row where Woolf’s home stood: that is now a residential hall for international students. There is a commemorative plaque for H. D., but no record of the other four women. Wade acknowledges that all five of them had “significant advantages of class, race, and education”—you would need all that and more to live there today. Though the arduous and rarefied literary world it describes has long vanished, this book feels vivid and contemporary in a London where accommodation and property seem to determine who gets to be a writer or thinker. Against all that, Square Haunting pitches its lineage of radical community and solitary labor.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence will be published by New York Review Books in September 2020.