Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

A writer and his doppelgänger traverse NYC in Antonio Muñoz Molina’s fragmented novel.

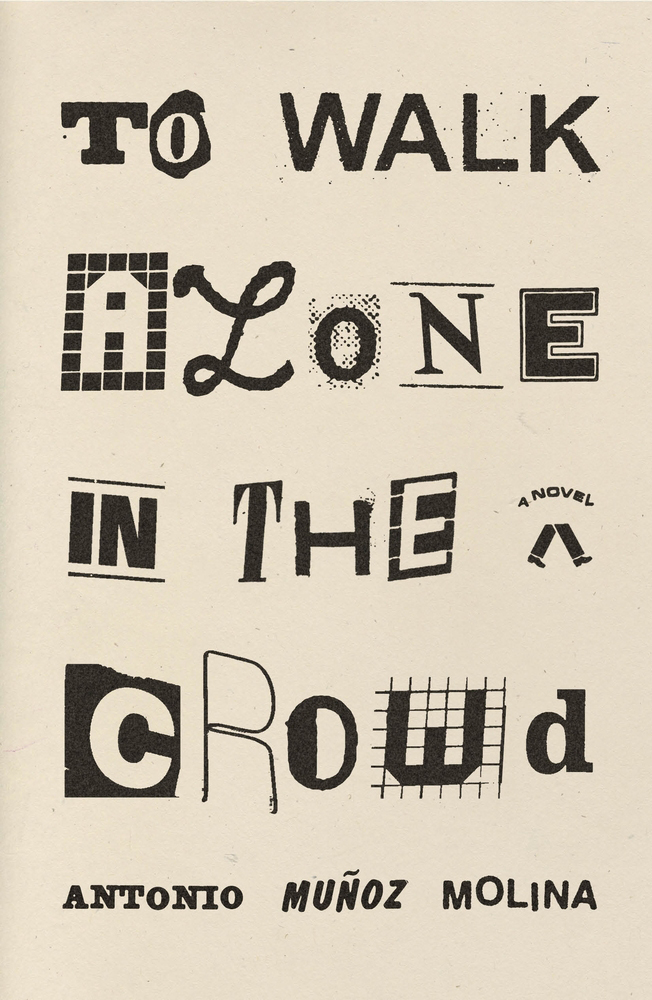

To Walk Alone in the Crowd, by Antonio Muñoz Molina, translated by Guillermo Bleichmar, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 419 pages, $28

• • •

“A 3D jaw can give you back your smile.” “Twelve people arrested for spreading false reports of creepy clowns.” “We are working to make your dreams come true.” Slogans and headlines wink and flash in Antonio Muñoz Molina’s kaleidoscopic novel To Walk Alone in the Crowd, living for a moment in distracted urban minds, recorded for posterity by a nameless protagonist. Like Molina, this earthly recording angel is a Spanish writer in late middle age, dividing his time between Madrid and New York. It is 2016, and he has recently recovered from a depressive episode. Like the narrator of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Man of the Crowd,” convalescence has made him voracious for city sights and sounds: “I am all ears. I listen with my eyes.” As in Poe’s tale, his street haunting is shadowed by a mysterious male figure—a vagrant and perhaps mocking double, always ducking out of sight and hard to recall clearly.

One of the scraps of advertising or news that Molina (or his fictional stand-in) quotes is this: “Timeless literature is back like never before.” The sentence is a small temporal spiral that leads reflexively, ironically, to the novel’s own predicament: in To Walk Alone in the Crowd, Molina has employed the ventriloquist machinery of high Modernism to capture—more than a century later—the present. It is not only that his narrator resembles a figure out of Baudelaire, Poe, or Joyce, all of whom he has been reading; nor that the book bristles with advertising copy and newsprint, just like Ulysses. (With this difference: Leopold Bloom is a copywriter—he makes the city, he doesn’t just read it.) More than all that, the fragmented form of the novel is borrowed from Walter Benjamin; each short essayistic section is titled after a gobbet of text or speech from the contemporary urban babel: a trick straight out of Benjamin’s One-Way Street. The question is: Can the literary techniques of the 1920s tell us much about today, or is this an exercise in knowing nostalgia?

“Unreal City,” T. S. Eliot says of London in The Waste Land: the modern metropolis has long seemed to be dissolving into fleeting images or voices in the ether, so that lives lived in part online today may seem merely to fulfill prophecies made in the twentieth century by newspapers and magazines, radio and television. Molina’s recuperating writer listens in on cellphone conversations, reads screens over shoulders on the subway, feels the surge of information in the streets: “many more vibrations than my crude human ears can detect.” He pays attention to “the lavish verbal succulence” of advertising, which now scrolls past in liquid crystal instead of insisting via paper and ink. All of it seems to him both vivid and fake; by contrast, he cherishes certain modest and graspable actualities: his notebooks and pencils, the scissors with which he cuts words and images from magazines, the familiar sounds and smells of a café.

But To Walk Alone in the Crowd is not exactly a nostalgic defense of materiality in the face of digital evanescence. Check the date again: it is the time of Trump’s ascendance, the idiocy of Brexit, the truck attack in Nice, an epidemic of those “creepy clowns”—and the usual litany of international atrocities, including the burning alive of a woman in Nicaragua, believed to be possessed by evil spirits. The material world, in other words, is alive and very unwell. Worse, it has replicated to a catastrophic degree; the waste of human civilization—which, from Baudelaire to Benjamin and beyond looked as if it might be remade as art or poetry—threatens to undo the planet by the middle of this century. During a period spent writing (writing this very book, it seems) in New York, the narrator finds he is assailed by bad versions of materiality: “I now admitted to myself that I had never stopped feeling helpless and afraid in this country.” The streets are filled with homeless people, nobody will look you in the eye, and a woman walks toward him clutching what appears to be a basket but turns out to be her fingernails, grotesquely overgrown.

It’s among such people—descendants of Baudelaire’s rag pickers—that the writer meets, and then keeps thinking he has spotted again, his doppelgänger. A nondescript scholar with a battered black satchel, likewise a collector of urban ephemera, also an adept of the walker-writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: Herman Melville, Joseph Roth, Fernando Pessoa. (Molina never mentions their later avatar, W. G. Sebald, trudging around Europe with his own satchel, amassing his fragments, dreaming of the awful past.) This elusive “Mr. Nobody,” who the narrator tells us is the para-academic inventor of the field of “perambulation studies,” seems the ghost of Benjamin, whose desperate, penurious flight from the Nazis Molina retells. (Always, reading of Benjamin’s last days, there is the fond, foolish hope of some last-minute salvation at the Franco-Spanish border.)

There are several such miniature biographies in To Walk Alone in the Crowd: portraits of Baudelaire, Poe, Melville, and others in extremis, their works to be celebrated only posthumously. These stories give the novel some of its antique, near-Sebaldian flavor, which sits more easily than one might expect alongside reflections on the digitally mediated city. A clue to Molina’s most obvious archaism: in describing his novel I have so far not mentioned a single female writer or artist. There are brief passages on Emily Dickinson’s stitched-together books of poetry, on Mrs Dalloway and Virginia Woolf’s suicide, on the photography of Diane Arbus and Vivian Maier. But for the most part, in a novel that purports to be as much about the present as the ways we discover what, and who, has been neglected in the past, women seem to function in this book as local color, at best. At times it is genuinely (deliberately?) like reading a writer from a hundred years ago: his wife is at home with her beautifully ordered household, while the author is abroad, eyeing up adverts for massage parlors. “The city speaks the language of desire.” Whose?

To Walk Alone in the Crowd is at once brilliant, erudite, absorbing, moving—and quite quaint, a sort of literary consolation, assuring us that defunct forms can still give us news about now. It is also a book that could only have been written today, as an act of engaged nostalgia: not so much for the materials and materiality that it constantly hymns, nor for the lives it describes at great historic remove, but for the sort of writing that detailed such things, the first time around.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on Affinities, a book about images.