Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

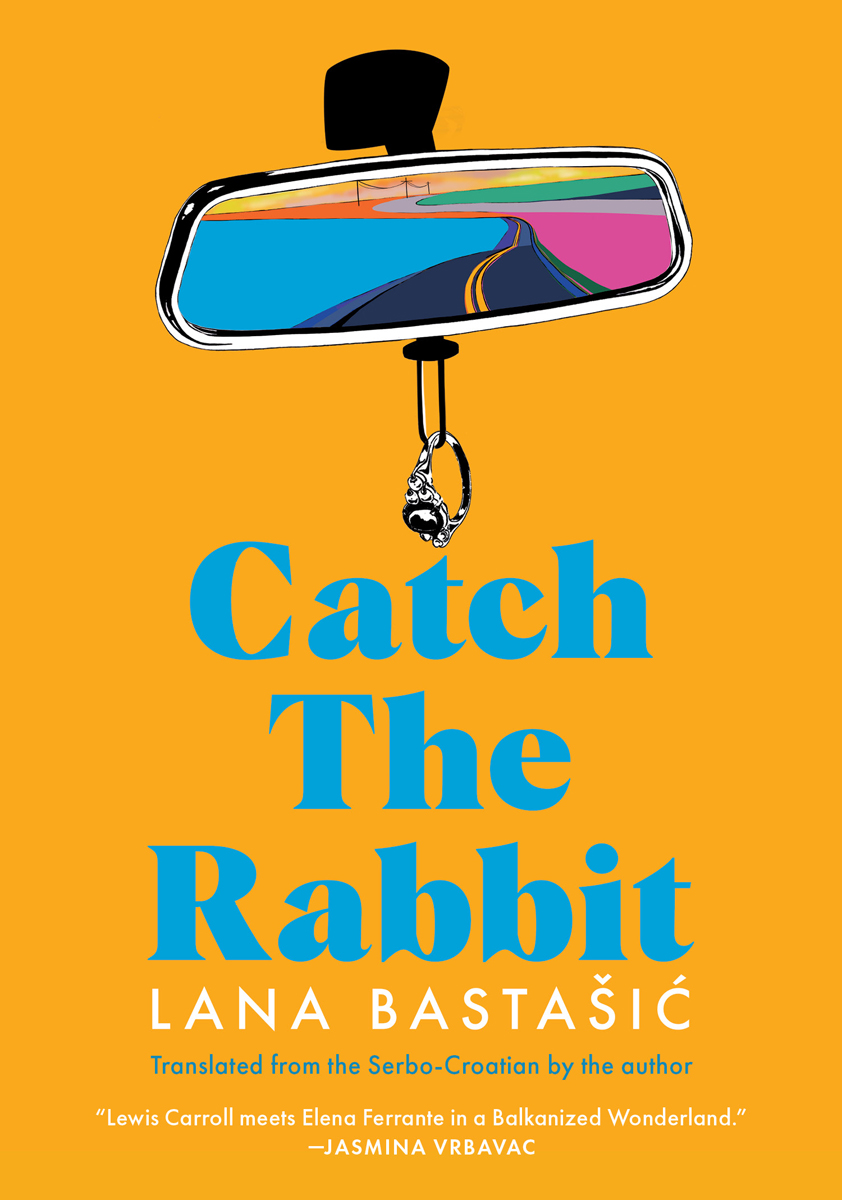

From Lana Bastašić, the winnner of the 2020 European Union

Prize for Literature.

Catch the Rabbit, by Lana Bastašić, Restless Books, 248 pages, $18

• • •

What happens in Lana Bastašić’s Catch the Rabbit is, per the author, modeled on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Both books are told in twelve chapters and follow an improbable chase initiated by an equally improbable white-haired creature. In Catch the Rabbit, the narrator, Sara, travels to meet Lejla, a long-lost friend with bleached hair. Together, they set out across Bosnia to find Lelja’s older brother, Armin, who has been missing for years and might (just maybe) be in Vienna. When the friends reach their destination, they post up at the Fröhlicher Jäger (Happy Hunters) hotel, a riff on the Enchanted Hunters motel from Lolita.

Bastašić grew up in Bosnia and lives in Belgrade now, but wrote Catch the Rabbit in Barcelona, where she cofounded a writing school called Escola Bloom. She translated the book into English herself, and it won the 2020 European Union Prize for Literature. (She was the laureate for Bosnia and Herzegovina.) Her Sara is a ferociously satisfying narrator, and though the subject of this book has already been adduced as some kind of Ferrante friendship X-ray, that shortchanges Bastašić’s skill. The heart of the novel is a braiding of time and love.

That Lejla and Sara are not related by blood is a minor factual distraction—their realities are constructed with and through each other. “Everything existed for us and because of us,” Sara writes. “The treetops with birds exploding out of them, the decrepit walls of Kastel, the broken branches carried away in the fast river, the smells sneaking out of the waking bakeries, the desolate streets with mutilated sidewalks—they were ours.” The most relevant literary precedent is Álvaro de Campos, whom Sara briefly mentions with the proviso that he “never existed in the first place.” Campos was one of Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa’s heteronyms, the name for a poet that Pessoa both was and was not. To hold someone close who is both immediately familiar and possibly no longer there is what Catch the Rabbit worries over.

Each chapter has two layers: in the first half, Sara tracks events in the present, and in the second, she uses her time at the Fröhlicher Jäger to record childhood memories of Lejla. In the opening, Sara is living in Dublin with a gentle man named Michael, relatively content. Absent for twelve years and living in Mostar, Lejla calls to say that Armin is alive, in Vienna. This hypnotic trigger sends Sara down the rabbit hole, and that’s it for Dublin and Michael. “I go into the first Starbucks I pass and buy a plane ticket to Zagreb online, Munich connection, 586 euros,” Sara says. (No direct flights to Mostar.) Lejla is the childhood love demon who Sara doesn’t know how to ignore, someone whose approval doesn’t feel absolute even when it’s been granted and must be sought all the harder for it.

Where Lejla is hard, her brother Armin is gauzy and dark. One day, when Sara was twelve, he performed the one tender act we hear about in the book. Standing in the garden, while they both looked for a lost earring (a loss Sara had just invented), he proved the existence of a grace otherwise absent from the story. “Covering me like a tree, he pulled the bobble and untied my ponytail,” Sara says. “He was gentle—like it wasn’t the first time he had done it.” In this moment of transcendence, time and identity vanish as if they were medical gowns meant to be tossed. “And I thought to myself that I wasn’t twelve, but a hundred and twelve, and that I had spent that whole century waiting for Armin Begić to set my hair free.”

Armin is accused by neighbors of poisoning dogs, a moment of the war intruding on the girls’ friendship. “Death is gradual at first, then sudden,” Sara writes. “In the beginning, dogs died one after another.” A neighbor named Mrs. Ristović loses her Serbian hunting dog, Luks. “That scum’s gonna poison our food while we’re sleepin,” Mrs. Ristović says. “First the Serbian tricolor hunters, then the Serbs. Mark my words.”

Armin is one of many boys who simply vanished in the nineties. Another, Ozren, is found floating in the river, castrated. These details are the casual brutalities that frame the story and provide a kind of metric. Though it’s only made clear in asides, Sara is Serbian (Orthodox Christian) and Lejla is Bosniak (Muslim). Bosniak marks an ethnicity, while Bosnian denotes citizenship. When Lejla Begić becomes Lela Berić in high school, the purpose is clear to a Bosnian. On the eve of a vast ethnic cleansing, this is how a Bosnian mother protects her child, changing her name to save her life.

Lejla’s confidence both infuriates and hypnotizes Sara. When Sara arrives in Mostar, Lejla walks away from her waitressing job and a giant husband named Dino without blinking. As they drive toward Vienna, Lejla throws cassette tapes and tampons out the window. When Sara complains about the half-life of plastic trash, Lejla takes the Bosnian view. “At least we’ll leave something behind.”

But Lejla remains Sara’s north star, a math whiz who used to turn tricks and maybe still does. After Lejla disappears in Vienna with a stranger and Sara finds three hundred euros in their room the next morning, she tries, fruitlessly, to rewrite her memories. “I imagined it all differently,” Sara says. “I wanted sunshine, and breakfast, and Lejla without makeup. Naive talk about times past. But the day was gloomy, like before rain, and those three hundred euros soiled its whole purpose.”

Recalling and examining that “naive talk” is how Catch the Rabbit shines. The split chapters make it clear that the search for Armin is only half the story and maybe not even the important half. Lejla is the person who either watched Sara become a writer or caused this to happen and, at this level of cathexis, it may not matter. Sara writes for Lejla, and in this book, she writes Lejla. “You dragged Lela’s name around toilets. I dragged Sara’s around literary magazines,” Sara says to Lejla. “In the end, isn’t that the same thing?” Sara’s resentments of Lejla are twinned with gratitude, a sense that Lejla is still the only person who understands her. “I never had to explain anything to her, she had the right magnifying glass for my inner turmoil.”

The story is a loop, ending with a broken sentence the conclusion of which opens the novel. Sara’s Wonderland journey does not lead back to any single home but to her own riverbank, to the selves that exist in and through the writing. “One of my stories or poems would get to you, whether you wanted it or not,” she says. “You would have to read it under my stupid, monolithic name. You would have to listen to me.” Sara doesn’t need to catch Lejla, because Lejla happens every time Sara writes.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.