Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

In a new hybrid memoir, Hélène Cixous explores the ghosts of her

late mother’s hometown.

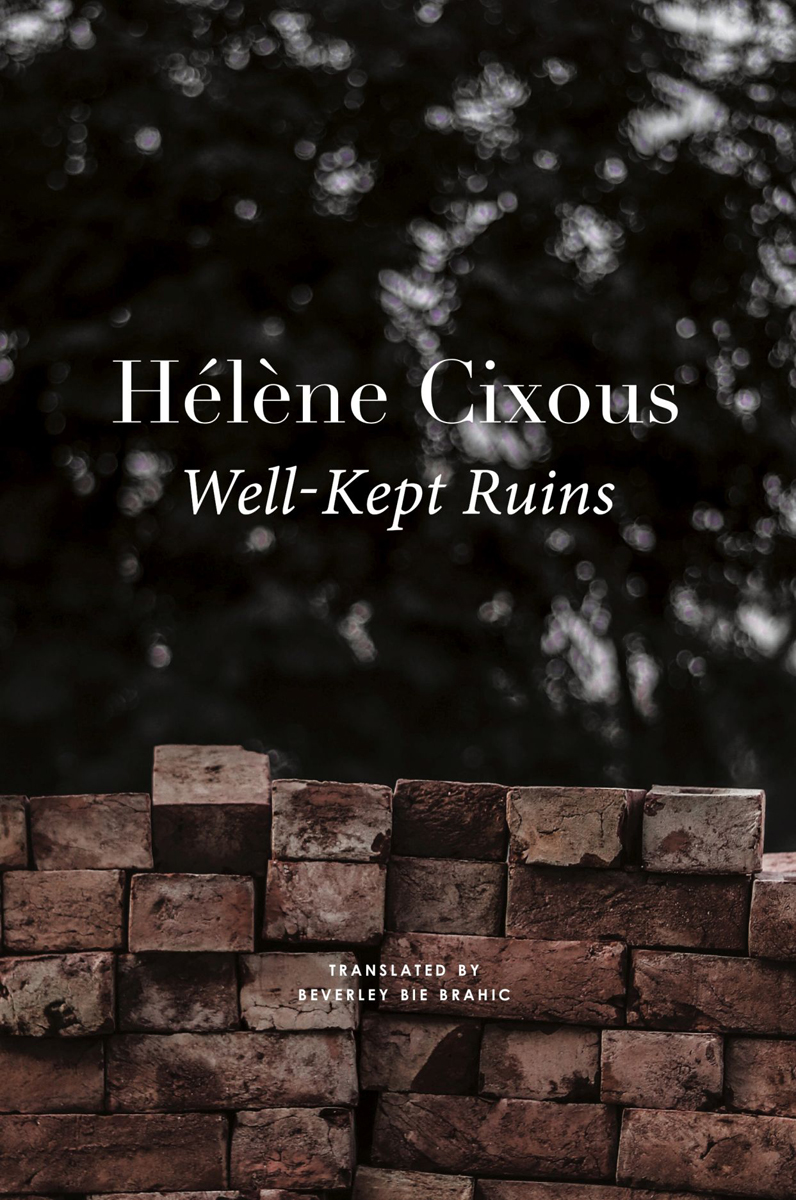

Well-Kept Ruins, by Hélène Cixous, translated by Beverley Bie Brahic, Seagull Books, 147 pages, $21

• • •

“Write your self. Your body must be heard. Only then will the immense resources of the unconscious spring forth.” Hélène Cixous’s extraordinary essay “The Laugh of the Medusa” (1975) addresses itself almost entirely to the future of women’s writing, not its history: “Anticipation is imperative.” Even (or especially) at the height of her Anglophone intellectual renown—alongside contemporaries like Jacques Derrida and Julia Kristeva—it was hard to get a sense of where the thrilling prolepsis of her writing had sprung from. (A university café in Dublin, late 1988; my friend rushes in clutching a book by Cixous: “I’ve no idea what she’s talking about, but this is brilliant!”) One knew that she shared with Derrida a Jewish Algerian background—but it’s only in recent decades (she is now eighty-five years old) that Cixous has described that history in detail, in works like her childhood memoir, Reveries of the Wild Woman (2000). Well-Kept Ruins is a moving, allusive, and formally daring addition to this late retrospective, autobiographical turn.

The central figure here is the author’s mother, Eve Klein, who died aged 103 in 2013. She had grown up “German with no illusions” in the small Lower Saxony city of Osnabrück and fled before the Nazis took power. They did not drive her out, she said, because she had a bag packed and claimed French nationality in advance. In Algeria she married Georges Cixous, and after his death from TB in 1948 she became a midwife: a profession she pursued beyond Algerian independence until the expulsion of French medical practitioners in 1971. Eve did not visit Osnabrück again until the 1990s, when the town authorities sought to make symbolic recompense for the deportation and murder of its Jewish citizens. The city’s short-lived synagogue, built in 1906, had been burned down in 1938, during Kristallnacht. Eve and other survivors, on returning, were uneasy stand-ins for the dead: “everything is instead of everything else in this little city.”

This is the place Cixous visits in the years after her mother’s death. (Well-Kept Ruins was first published in French in 2020; an earlier book, Osnabrück, 1999, covered some of the same history while Eve was still alive.) A city through which Johannes Kepler is said to have passed—he did not stay. A city whose Bucksturm, a former watchtower, later used as a prison, once housed the fifteenth-century nobleman Johann von Hoya in a tiny oak cell, still preserved as a museum artifact. In the same tower, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, hundreds of women were incarcerated as witches pending their trial and execution, or execution by so-called water trial. A narrow lane or passage runs to the tower, reminding Cixous (though she notes it only glancingly) of the wired and forested corridors that led into certain Nazi death camps. Of the Bucksturm’s part in the imprisonment, transport, and killing of the city’s Jews, not a trace remains. Cixous is engaged, she writes, in a type of archaeology: “to unearth the city’s hidden force.”

The ruins of the title are the remains of the burned-out synagogue, recalled only in contemporary photographs and a current memorial made of stones enclosed in wire mesh cages. This latter, says Cixous, looks like “a calcified chicken coop, or perhaps an expressionist rendering of Niobe’s tears.” Her son remarks it’s like something you’d see in a garden, the last word in tasteful landscaping. A ruin ruined: the discretion, tastefulness even, of the memorial undoes memory—which is perhaps its real municipal intention. “The whole city cleaned up, rebuilt.” Against this product of Osnabrück’s civic bad faith, Cixous pitches the material refuse of her mother’s life. Suitcases filled with photographs, paperwork, the speculum Eve used in her midwifery, a strange neatly written list that over three fading pages seems to narrate her journey between Germany, Algeria, and France. “We are transported, my mother and I, into the generations and archives of our interior and outer towers.”

“Osnabrück is a fiction,” Cixous says. It is, and it is not. Much of what she writes in Well-Kept Ruins is precise, detailed, dutiful in its attention to the relics in front of her. But a good deal of the book unfolds in a dream state, the author projecting herself into the past with all the daring that, as critic or theorist, she used to throw herself into the future. “I like being in 1648 in October 2019.” Cixous’s voice gives way regularly to the voices of her mother, her son, her daughter—to the voices of Osnabrück schoolgirls who appear alongside Eve in an old photograph and then, transformed, in a later one. The book drifts easily, sometimes confusingly, between memoir, the reported memories of others, and what must be imagined. And then there are Cixous’s dreams: in your eighties, she writes, you dream of being two years old. She is back in Oran, Algeria, and everyone is packing suitcases to flee. “And as usual at the border with the next dream, I see that disheartened man who could be a cousin, it’s Walter Benjamin the man who can’t close his suitcase.”

There are just two direct invocations of Benjamin in Well-Kept Ruins—but he is in a sense the book’s patron saint, emblem of exile, ruin, and remembrance. Also of erudition: Cixous’s prose is as replete as ever with mention of other writers. If there is a kind of late-style casualness here, it’s accompanied by teeming reference and citation. Early on, Montaigne in his tower, essaying the examined life, seems to inspire her retreat into memory—as well as rhyme with the Bucksturm. There is Marcel Proust’s narrator, losing his way with words as he drags himself out of a dream. And Edgar Allan Poe more than once, though translator Beverley Bie Brahic seems to occlude an obvious quotation of “The Purloined Letter” when she has Cixous describing something hidden in plain sight as “a striking instance of the stolen letter.” For the most part, however, this welcome translation gives us a Cixous still energetically writing the self, and other selves—this time with imperative retrospect.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities: On Art and Fascination will be published by New York Review Books in spring 2023. He is working on a book about Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love.