Momtaza Mehri

Momtaza Mehri

Boundaries between sleeplessness and surveillance are blurred in an artist’s constructed bedroom scenes.

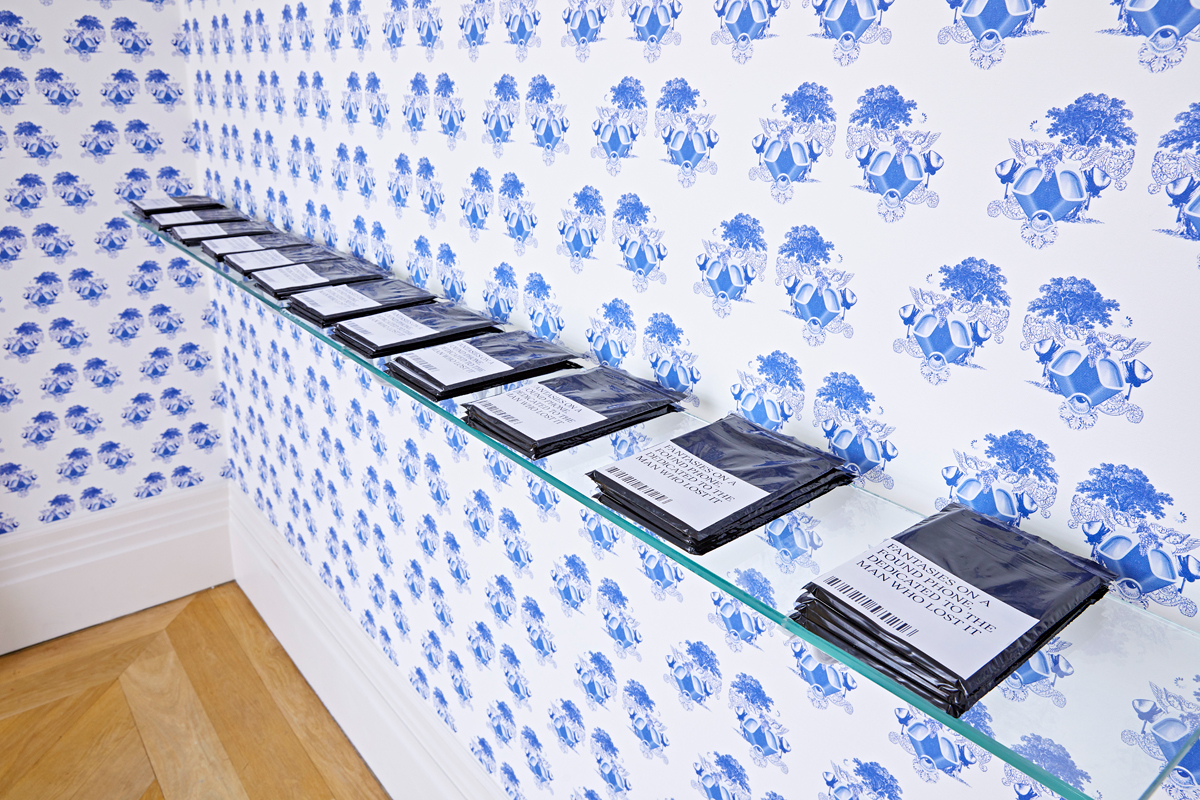

Mahmoud Khaled: Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, installation view. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg.

Mahmoud Khaled: Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, The Mosaic Rooms, 226 Cromwell Road, London,

through September 25, 2022

• • •

The insomniac yearns for privacy. Simultaneously alone and taunted by the ghosts of his waking hours, he has little control over what crawls into bed with him. In Alexandria-born artist Mahmoud Khaled’s latest—and first UK solo—exhibition, the insomniac in question is also a man who has lost his unlocked phone in a public toilet. Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it probes the digital crevices of a stranger’s life, creating what Khaled describes in the press release as a “spatial portrait of an absent person.” Like the distinctions between fact and fiction, Khaled softens the boundaries between the phone owner’s conscious self-documentation (photographs, notes) and the wispier traces of a guarded personality. We aren’t sure if this sleep-deprived everyman is real, but what is certain is how attentively Khaled’s constructed scenes of intimacy poke deep into the bowels of the devices we carry with us. This isn’t new for Khaled, whose works commemorate, restage, and reconfigure absences of various kinds.

Inspired by the obsessively devotional drawings of German artist and Symbolist Max Klinger, Berlin-based Khaled frames the lost phone as a rich repository of interiority, like an open diary to be pored over. Klinger’s series of etchings Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove (1881) turns a glove dropped by a woman at a Berlin skating rink into a fetish object. No longer just an extension of the beloved, the glove soaks up the potency of the encounter between Klinger and the woman, between the artist and his unwitting muse. The glove’s hallucinatory power initiates Klinger through imagined stages of triumph, homage, anxiety, and abduction. Khaled advances the unlocked phone as a doorway into a different kind of encounter, probing its ability to “speak on behalf” of an unknown person. Through Khaled’s installations and immersive sound compositions, we can access this stranger’s sleeping habits, circadian rhythms, innermost thoughts, transient desires, and awkward hesitancies.

Mahmoud Khaled: Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, installation view. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg.

Split across three rooms, the works invoke the insomniac’s states of agitation and restlessness. Enter the first gallery, wallpapered with a Victorian-style pattern of urinals. As Khaled puts it in an interview with Studio International, this is the “domestic environment” he seeks to flesh out from the impersonal obscurity of the found phone. A photograph of an unmade bed hangs in the room, the cursive scrawling across it begging to be deciphered: I can’t sleep without you anymore. Like in a glove, an accompanying artist’s book fits snugly in a black case resembling a polyethylene wrap of secrecy. We are encouraged to flick through the book, prying into the phone’s contents: topless selfies, memes, excerpts from James Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room misspelled in the private nooks of the Notes app, gay erotica, images of pensive statues, dating-app screenshots, photographed sweat patches on crumpled sheets. Rooms of rest. Public restrooms. Both the urinal and the unmade bed are presented as incubators of fantasy and voyeuristic participation. Leafing through the book is akin to rummaging through someone’s bedside drawer. It feels guiltily lush.

Mahmoud Khaled: Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, installation view. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg.

In another room, part of the installation Calm (2022) recreates Yearnings, the third plate in Klinger’s Glove series, in two side-by-side blue-and-white wall paintings—a chinoiserie of melancholy. With its leather bondage-strapped daybed, velvet curtains, and soothing narration emanating from overhead speakers, Calm is awash with imperatives. Close your eyes. Take a deep breath. Breathe out. Bird trills and raindrops trickle as a woman’s hypnotic voice asks us to find a comfortable position and relax our bodies. Despite these suggestions, the daybed’s ornamental, Freudian quality doesn’t exactly welcome lounging (I didn’t see anyone moved to recline on the daybed, and personally, it didn’t feel right to). The sound component of Calm functions like a sleep app, perhaps used by the unknown man himself, to quell the tosses and turns of his mind. The onlooker becomes a “dear subscriber” to a hotline for the drowsily haunted. Much like the flickering glow of smartphones under covers, the sleeping app can be as much a technology of distraction as an escape from it. Unplugging from technology by using technology is a paradox Khaled jabs at. The work of rest concerns Khaled, who represents sleeplessness as a form of exile or dispossession; he is particularly interested in the draining effort needed to meaningfully recuperate from an outside world that threatens, disciplines, and criminalizes queer, unproductive desires.

Mahmoud Khaled: Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, installation view. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg. Pictured: Calm, 2022.

To the poet Fernando Pessoa, life was one big bout of insomnia. Khaled attests to the sound elements of Calm being inspired by Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet. Known for his exhaustive alter egos, the Portuguese writer’s technique of heteronyms parallels Khaled’s anonymous universe of the exiled and the disappeared. Plurality can be a place of refuge, a safety behind masks. The surveilled develop a contextual malleability, an ability to be who they need to be on any given occasion, retreating into a truer self only in the cocoon of a digital world. Some people are forced to protect their fantasies with passcodes. An unlocked phone then becomes an aberration, an isolated window into daydreams and night terrors that may be risky to publicly articulate.

Mahmoud Khaled: Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, installation view. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg. Pictured: For Those Who Can Not Sleep, 2022.

Downstairs, notions of reclination and restraint are further teased apart in For Those Who Can Not Sleep (2022), where a circular leather bed is the room’s focal point. Bondage straps reappear, affixing desire to helplessness. Hugh Hefner’s infamous rotating bed-office comes to mind. From the framed etching of Klinger’s Anxieties to the silver vase decorating the bedside, there is a staged domesticity to the scene. Again, we have the insomniac in desperate need of slumber-inducing props. A somber, bell-like piano refrain dominates this sonic element, and the longer you stay in the room, the more you feel you have intruded upon a shadowy chamber.

Mahmoud Khaled: Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, installation view. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg. Pictured: For Those Who Can Not Sleep, 2022 (detail).

Desperation is efficiently privatized. Khaled succeeds in collectivizing it through an unnamed, unknown individual. We share a baseline familiarity with the unsought wakefulness and inability to switch off that permeates contemporary life. Attention is attenuated, and this is as much a cause of private misery as it is a psychosomatic consequence of numbing addictions, absences, and social needs with technology. The staging of a life’s digital detritus continues Khaled’s exploration of the house museum as a medium, recalling his 2017 work Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (an installation that can now be revisited at London’s Metroland Cultures as part of the 2022 Brent Biennial). There, too, is the sustained interest in theatricality, architectures of suppressed desire, and how the institutional informs the spatial, though that earlier work more explicitly confronts themes of political witness and exile, themes which subtly simmer beneath the surface of Fantasies. Another thread is the porous relationship between the fictive and affective. As Khaled asks in an interview with art-agenda: “How do we commemorate an unknown person?” In posing this question, he invites us to make a dwelling out of it. His latest exhibition is a cohesive attempt to capture the ambient presence of a figure who reflects the hyperstimulated alienation of an entire age. What better state to reflect on such disjunctures than in the drift of LED-interrupted sleep? James Baldwin wrote of 4 a.m., the “devastating hour” where “one’s wounds awake and throbbing” erect a “prison of the self.” Like a bedroom’s threshold, or a fleeting peek into someone else’s phone, I see Khaled’s own invitation as a contract to enter into. Its pleasures are as resplendent as its pains, and are even better when we stumble upon them at our loneliest. The contract relies on a bidirectional responsibility: that we are as gentle with the personal archives of others as we would want them to be with ours.

Momtaza Mehri is a poet who works across criticism, translation, anti-disciplinary research practices, education, moving image, and radio. Her latest pamphlet, Doing the Most with the Least, was published by Goldsmiths Press.