Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

With newly available images, a show revisits the photographer’s work.

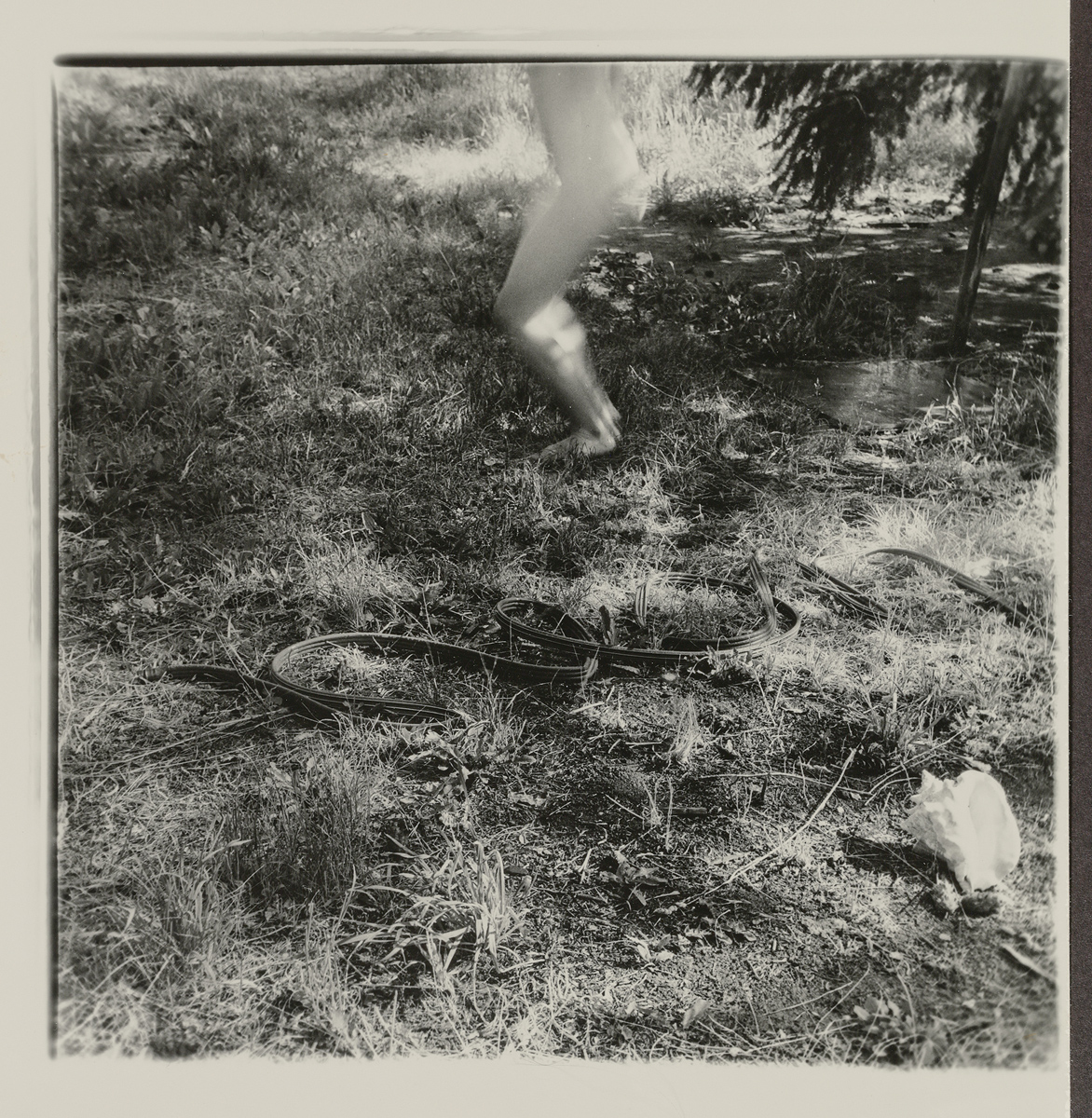

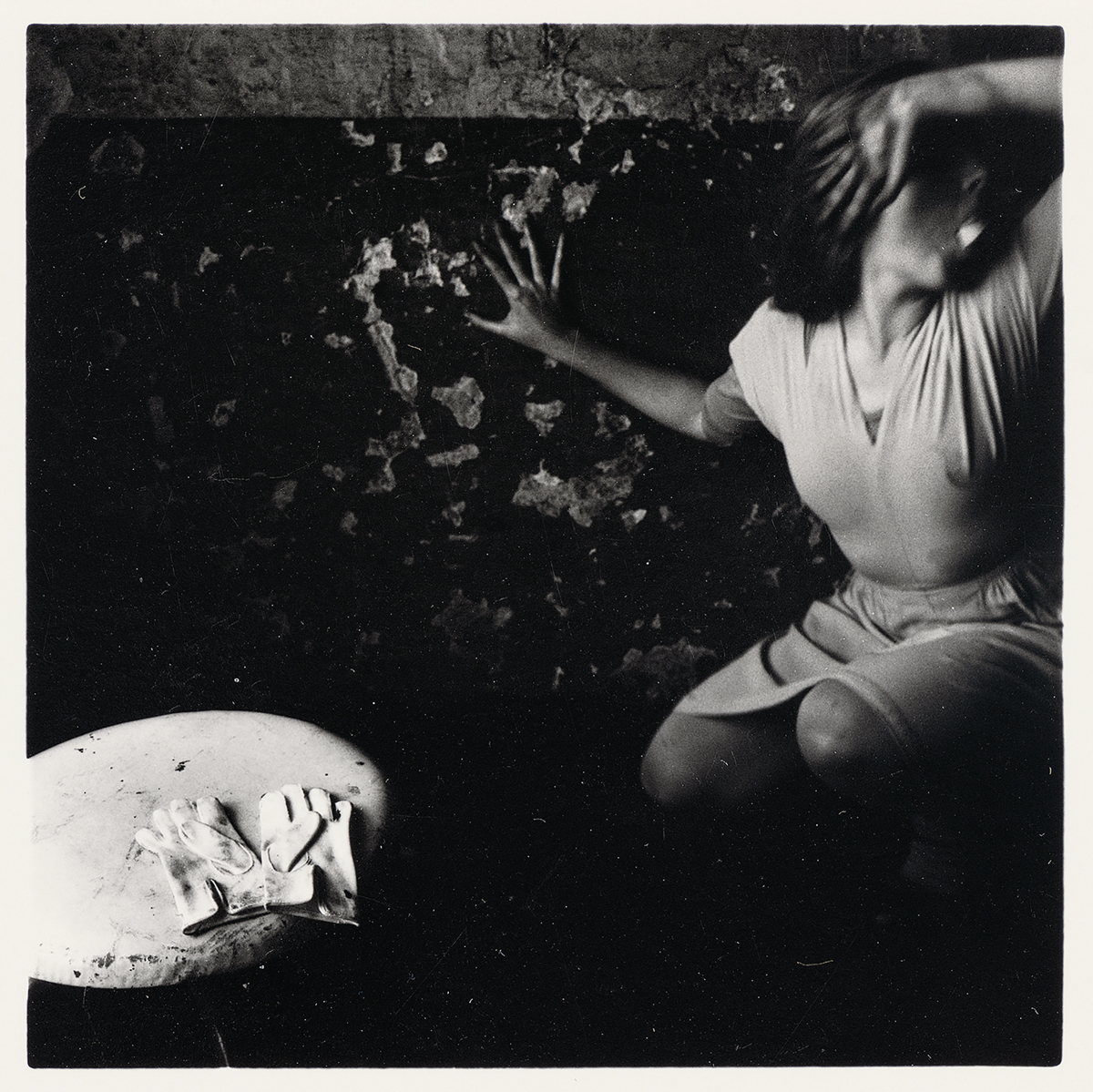

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Boulder, Colorado, c. 1975. Vintage gelatin silver print, 7 1/8 × 7 1/4 inches. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society.

Francesca Woodman: Alternate Stories, Marian Goodman Gallery,

24 West Fifty-Seventh Street, New York City, through December 23, 2021

• • •

The promise of twenty-one previously unseen Francesca Woodman photographs is the pulse-quickening hook for a new exhibition of her work at Marian Goodman Gallery. According to some sources, of the estimated eight hundred gelatin silver prints (and many more negatives) that the tremendously influential artist produced during her short, prolific life—Woodman died by suicide at the age of twenty-two, in 1981—less than a quarter were exhibited or reproduced while her parents were alive and managing her estate. Speculations and suspicions arising from both the manner of her death and the alleged suppression of her work were popular when I was in art school. No doubt they have circulated in the decades since, as her legendary status—as a tragic genius in feminine form, whose photo-class assignments were written about by Rosalind Krauss, whose blazing juvenilia is also her haunting mature work—seems destined to fuel passion and rumor online.

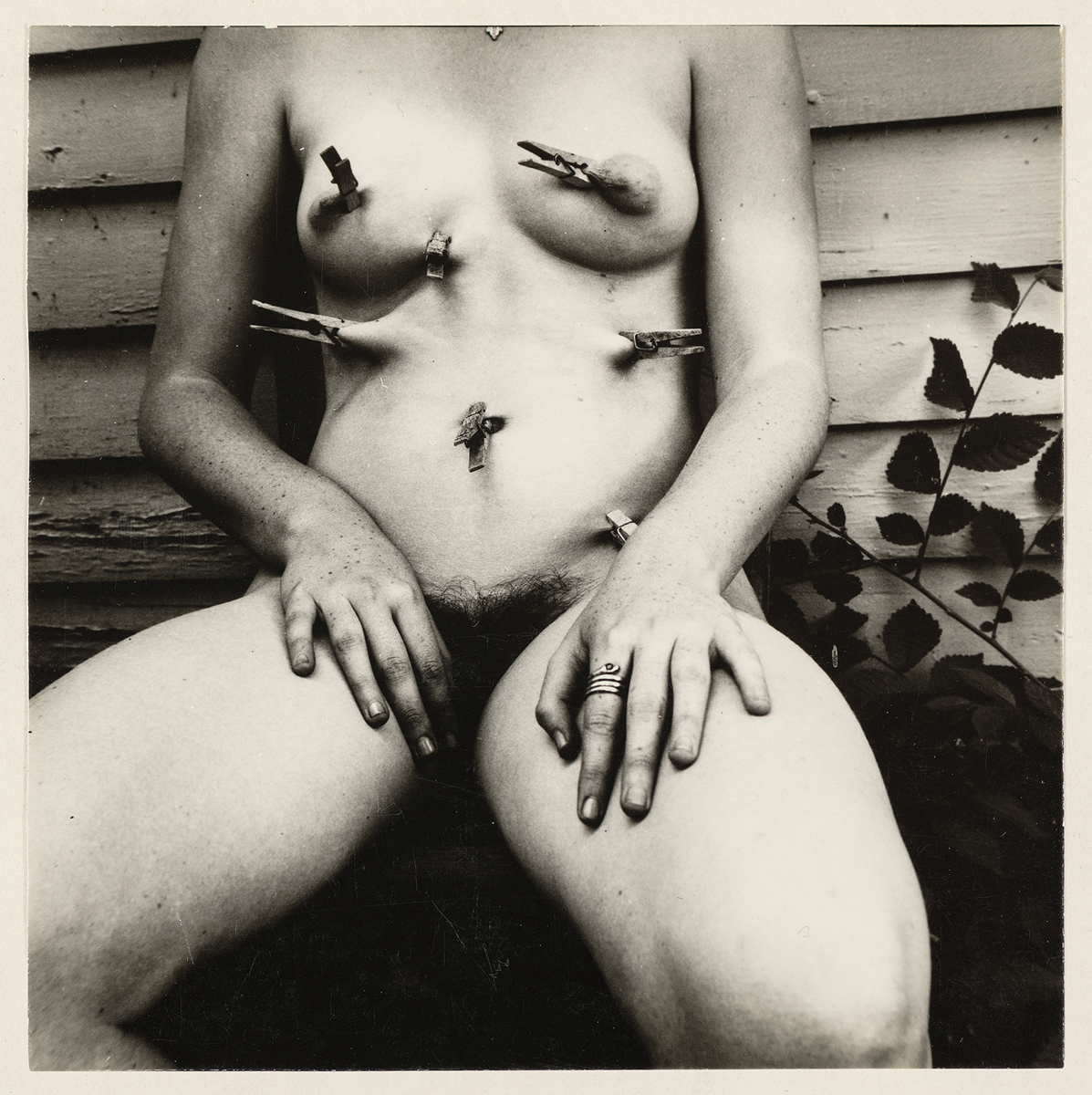

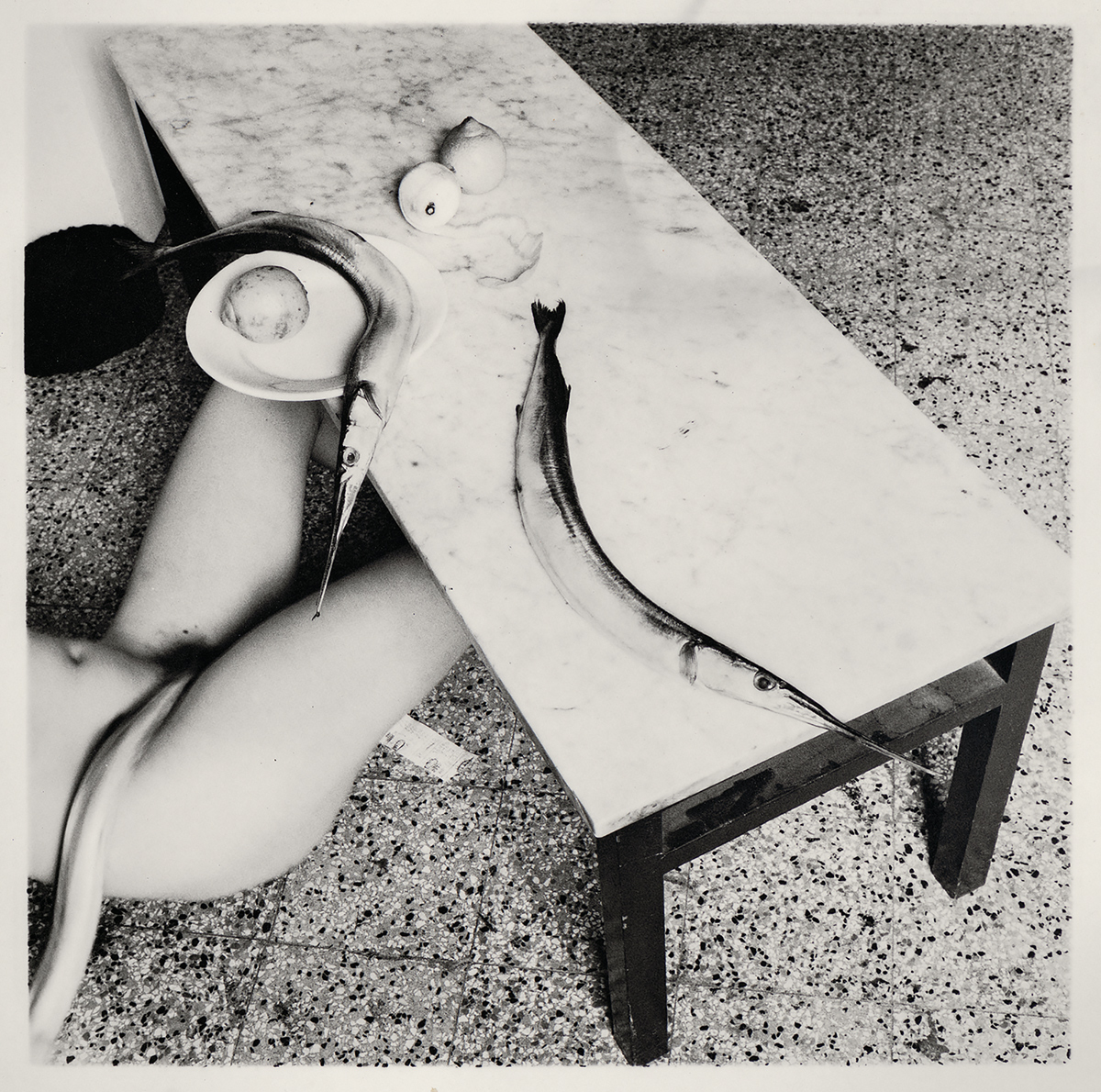

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Boulder, Colorado, 1976. Vintage gelatin silver print, 4 3/4 × 4 3/4 inches. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society.

In 2018, a year after her father’s death, Francesca’s mother, Betty Woodman (the well-known ceramicist), passed away; her estate bequeathed all existing archival materials to the Woodman Family Foundation. So, Alternate Stories—as this very beautiful, anti-sensational, quietly narrative-shifting show is titled—draws upon newly available vintage prints, correspondence, and notebooks, and it may signal a new era of access.

Francesca Woodman: Alternate Stories, installation view. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Alex Yudzon.

Despite the additional works on view here, the stylistically anomalous, formally exacting, and disconcertingly precocious Woodman remains a mystery. And her confidently spare, strangely timeless, black-and-white scenes, which often capture her own image within them—a pale figure, obscured, cropped, apparitional, amid ruins—are, as always, mysteries, too. Her pictures, usually only slightly bigger than her negatives, are like clues, inviting close contemplation, posing their own unanswerable questions. With fifty prints in total, the “new” ones are inserted, without fanfare, into thematic constellations alongside photos that will already be familiar to the Woodman fan. The excellent accompanying publication, which includes an essay by novelist-critic Chris Kraus, also integrates the fresh archival information into a more textured understanding of Woodman’s practice, detailing the artist’s processes of planning and improvisation—sometimes in her own words.

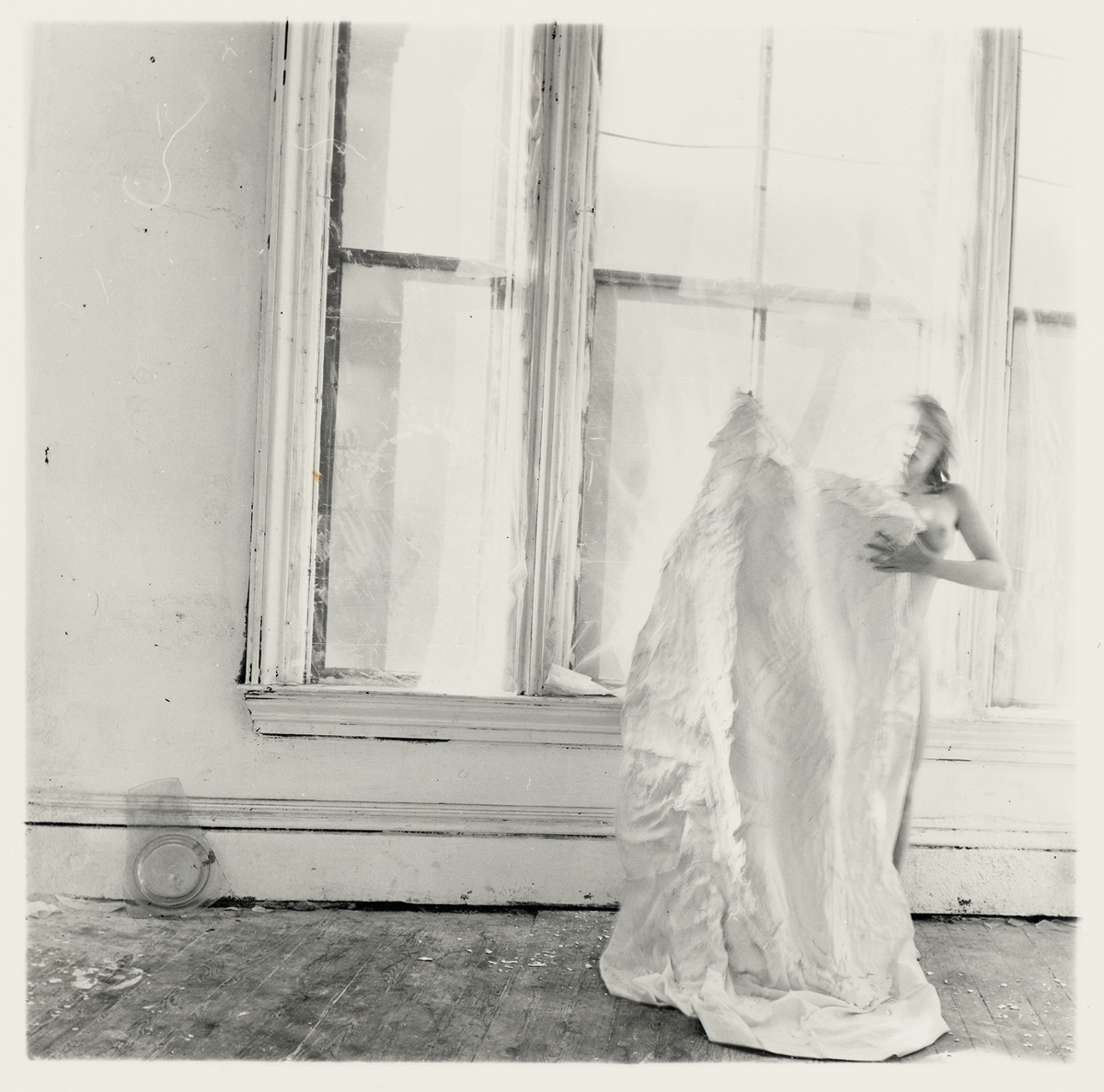

Francesca Woodman, A waltz in three parts, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975–78. Vintage gelatin silver print, 5 1/2 × 5 1/2 inches. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society.

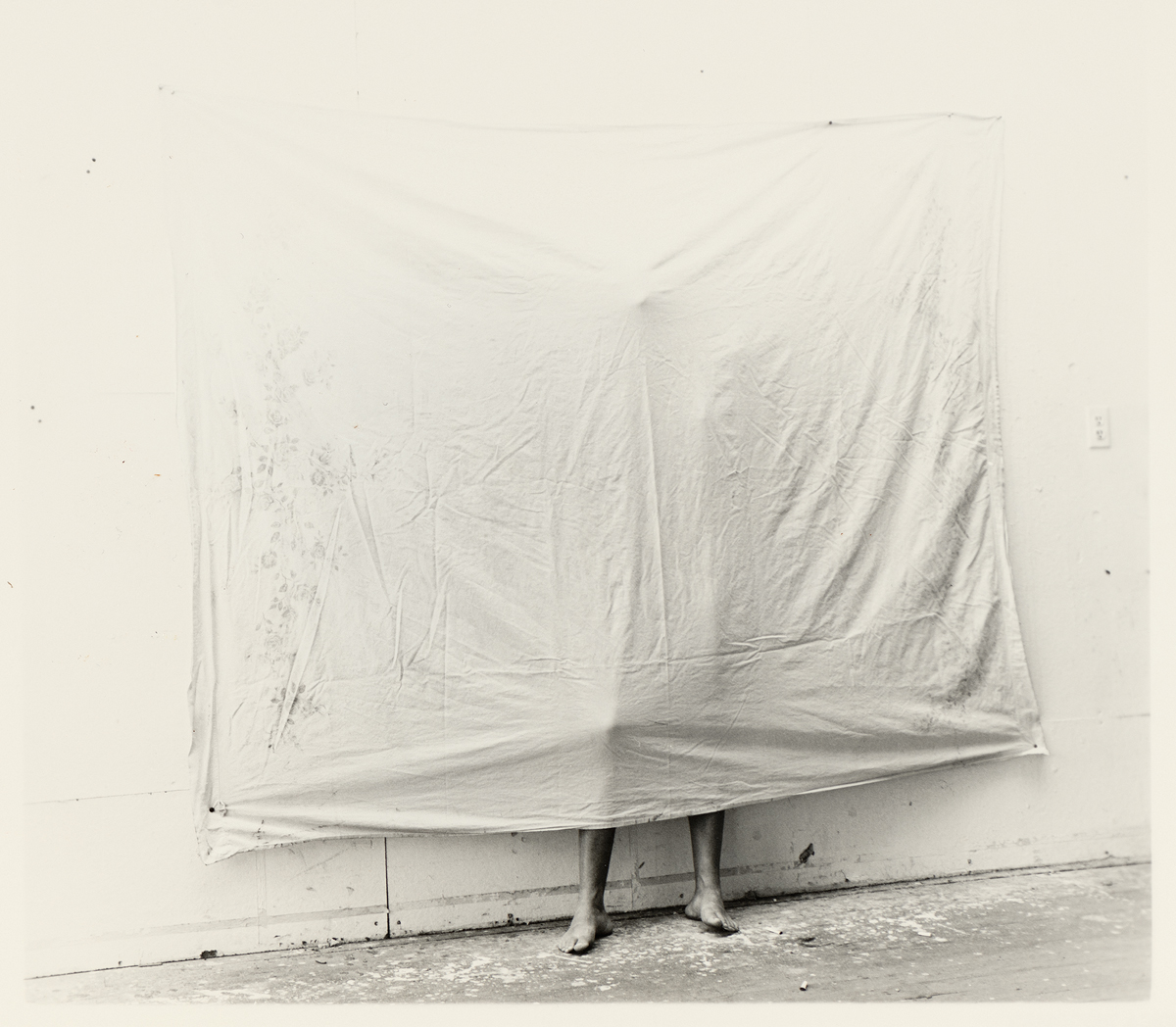

In an example of the show’s subtle curatorial approach, a pair of simple, but expansively allusive, shoots staged in her Providence studio, dated 1975–78—from the period when she attended the Rhode Island School of Design—are juxtaposed to illuminating effect. In both, Woodman appears nude. In one, represented by prints and a contact sheet, she works with a cast plaster form—it looks to be her own body, from the neck down. The ghostly or celestial, overexposed photo A waltz in three parts shows Woodman poised to dance with her truncated double, both figures disintegrating in the loft window’s white light. In the other series, the artist experiments with a faintly floral-patterned bed sheet. In the most striking image, which she left untitled, the fabric is pinned to the wall; she’s caught beneath it, her form articulated by its taut, angled lines.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975–78. Vintage gelatin silver print, 5 1/2 × 6 1/2 inches. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society.

Elsewhere, there are more extreme examples of Woodman’s tropes and tendencies—such as her interest in the look of Victorian decrepitude and long-exposure Spiritualist visitations, poses of bondage or containment, techniques of self-concealment and disappearing tricks. But it’s these particular pictures, with the plaster cast and the sheet, that, in showing her eerie ability to make dramatic use of mundane props, perhaps best demonstrate how she used her own body as a prop as well (rather than as a symbol or sign for the self). In 1979 she discussed, in handwritten answers to interview questions (which are newly available, reproduced in the catalog from her papers), “using nudes”—a surprising and telling way to describe her own presence in her work. “I use nudes partely in an ironic sense like classical painting nudes,” she explained. “I want my pictures to have a certain timeless, personal but allegorical quality like they do in say ingres history paintings, but I like the rough edge that photography gives a nude.” (Spelling hers.) When she stands, she is classical statuary; supine, she is a nineteenth-century odalisque; in motion, a Renaissance angel.

Francesca Woodman, Angels, Rome, Italy, 1977–78. Vintage gelatin silver print, 3 3/4 × 3 3/4 inches. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society.

But Woodman was engaged with more recent European art history, too. Raised in both Boulder, Colorado, where her artist parents had teaching jobs, and Antella, Italy, where they established studios in an old farmhouse, she became fluent in Italian—an indispensable skill for her college year abroad in Rome. This was an especially fervid time for Woodman. She connected with the artistic community in the orbit of the Maldoror bookstore, and found, in the city’s older architecture, derelict or antique backdrops that spoke to her aesthetic; the photographs she took in Rome help us understand her body of work as a whole. Her ragged classicism makes new sense seen through the lens of Surrealist and symbolist influences, apparent in the brash sexual metaphor of her sharper, higher-contrast Fish Calendar series (1977–78), for which she draped a long, eel-like fish between her bare thighs (a cropped, reclining pose), or held one, silvery and pendulous, at the crotch of her legs, the creature camouflaged somewhat against her black ribbed stockings. (“Usually after i have finished with the fish i take them over to the largo Argentina near the H. Minerva and feed them to the cats,” she wrote home to her parents.) There are shades of Hans Bellmer here, and a savvy fur-teacup inversion, as well as other, more elusive formal elements, belonging to Woodman’s distinct strain of provocation.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Italy, 1977–78. Vintage gelatin silver print, 3 7/8 × 3 7/8 inches. Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society.

Somehow, she did not lose her vision to nostalgia for a bygone avant-garde or craft a purely derivative one decades late—though that would have been an entirely age-appropriate thing to do. When Krauss, in the aforementioned essay, wrote about Woodman’s student work in 1986, she described it as a continuation and subversion of a modernist project. The photographer’s medium-specific acuity—her “constant reference to the inner laws of the photograph as it stills motion and holds its contents in eternal display”—converged with the existential concerns of the model: “What does it feel to be on display? What does ‘forever’ feel like? What would it be like to be, eternally, the center of someone’s gaze?” These were not Woodman’s questions, at least not in her words, and they were formed by the gaze-y feminism of the day. But they evoke the timeless feeling, and the motif of entrapment in her images—and I’ll always remember my teenaged shock that Woodman’s young work (which I loved) was taken so seriously, that someone my age could be written about in this way.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.