Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

The artist conjures a multimedia fantasia, with help from Mom.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, Pioneer Works, 159 Pioneer Street, Brooklyn, through November 24, 2019

• • •

It’s not difficult to find an entry point to Jacolby Satterwhite’s dizzying, ornate universe. In fact, it’s hard to find a spot to stand that’s not somehow a threshold to another of its desolate or exhilarating dimensions. The artist’s new exhibition You’re at home—a transporting, multimedia, queer fantasia in his singular style—is a maze of beckoning portals and bejeweled trapdoors, filling the gallery space of Pioneer Works’s cavernous ground floor with a pulsing, high-tech, and deeply personal exercise in recursion and excess.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

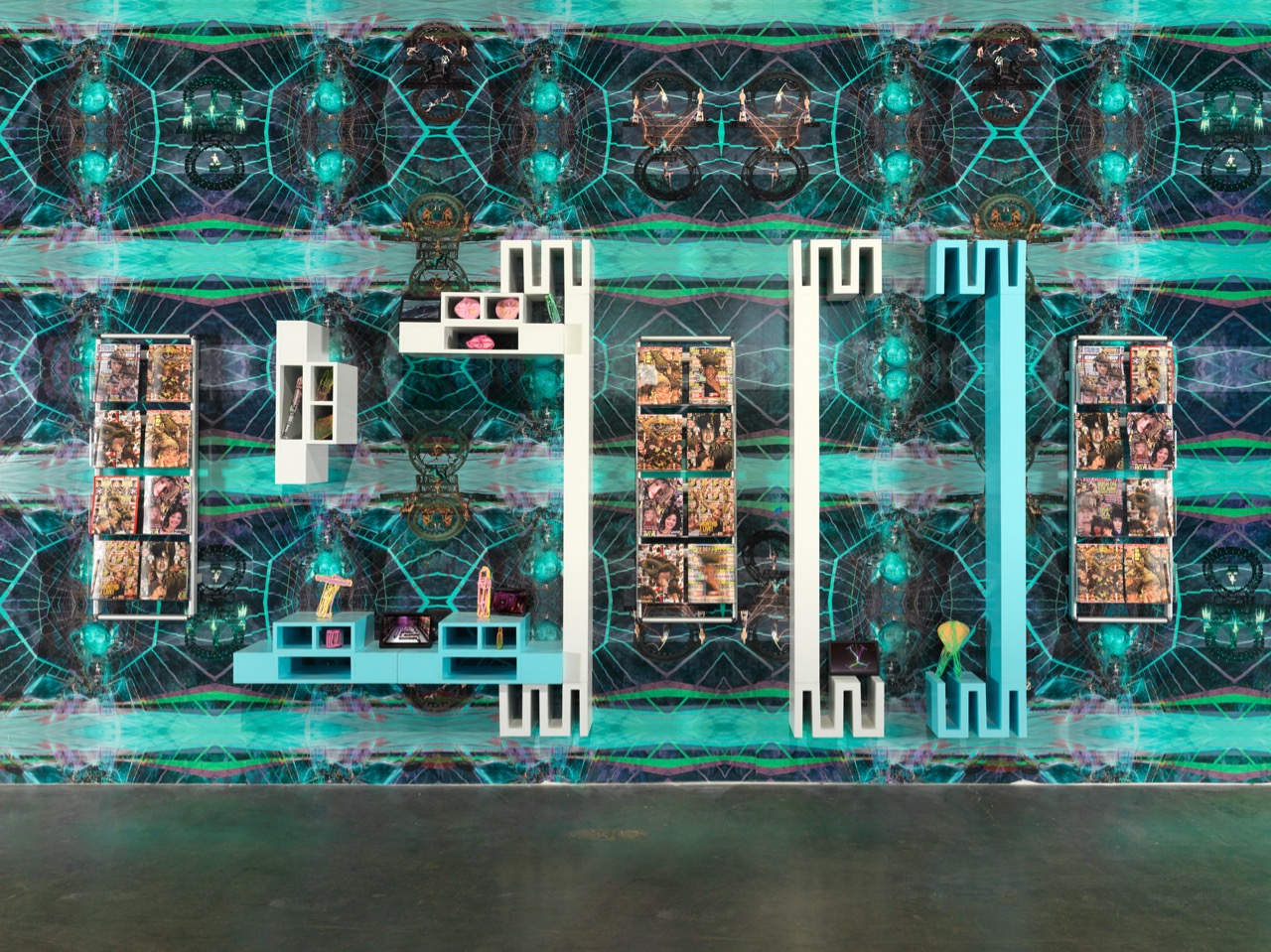

Satterwhite’s hallucinatory vision is realized through an all-encompassing more-is-more approach that includes green-screen compositing, kaleidoscopic and mise en abyme effects, and vintage 1990s and future-modernist installation design. His digitally animated and live action film, Birds in Paradise (2017–19), spans the back wall. A small phalanx of Tower Records–esque “listening stations” with VR headsets play vertiginous 360-degree videos set to the trip hop– and house-inflected tracks of his band PAT (a collaboration with Nick Weiss of Teengirl Fantasy). Retail displays are stocked with branded merchandise, as well as PAT’s new double-LP album, Love Will Find A Way Home. And zig-zagging modular shelving units hold tchotchke-scale sculptures and tablet-sized screens, mounted on walls papered with custom-printed, tessellating vignettes grabbed from his films.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

Then there is the transfixing imagery found in Birds in Paradise and throughout the exhibition—Boschian science-fiction scenes of debauchery and hard labor, featuring mythological creatures and references to African folklore. Gay clubs merge with purposeless, busy factories in rotating battlestar structures, out in space or in a vast, barren, coliseum-like structure. Simulated moving shots endlessly torque, pan, and zoom in or away from the action in this lubed-up Fordist dystopia, showing leather queens, dads, sexbots, and dancers (including the artist) voguing, fucking, working, and working out on monstrous scaffoldings, amid massive gears, conveyer belts, and forbidding industrial tentacles.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

Here, bodies are not individually expressive; they are mechanical parts and architectural elements in a harsh, sexual, semi-automatized dance idiom in which Satterwhite has metabolized both Ball culture, with its distilled drag theatrics, and postmodernist choreography, with its interest in pedestrian (everyday, unskilled) movement. (He cites pathbreaker Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s percussive, flashy, fidgety dances as an influence.)

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

The artist’s animation technique is obsessive and embroidery-like, but he leaves his work intentionally rough around the edges. DIY virtuosity rather than slick, outsourced illusionism rules, mitigating the chilly vibe endemic to such digital renderings. More than this “handcrafted” touch, though, it’s autobiography that tempers the distant feel of his otherworld. Footage of the artist dancing alone in a bathroom, in an empty club (Bushwick’s sadly defunct Spectrum, it looks like), or as the subject of outdoor rituals (we see him painted, bound with bandage-like cloths, hung upside-down, and baptized in a river) intercuts and intrudes upon the computer-generated material.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

He offers one more amazing, intensely personal, thing: almost the entire show is made, in part, from material left behind by his mother, Patricia Satterwhite, who passed away in 2016. Suffering from schizophrenia for much of her life, when not in the hospital she mostly stayed at home. But her dream was to become a pop star; she made cassette tapes of the songs she composed, recording her vocals a cappella. She was also an inventor, and longed to see her imagined products for sale on QVC.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

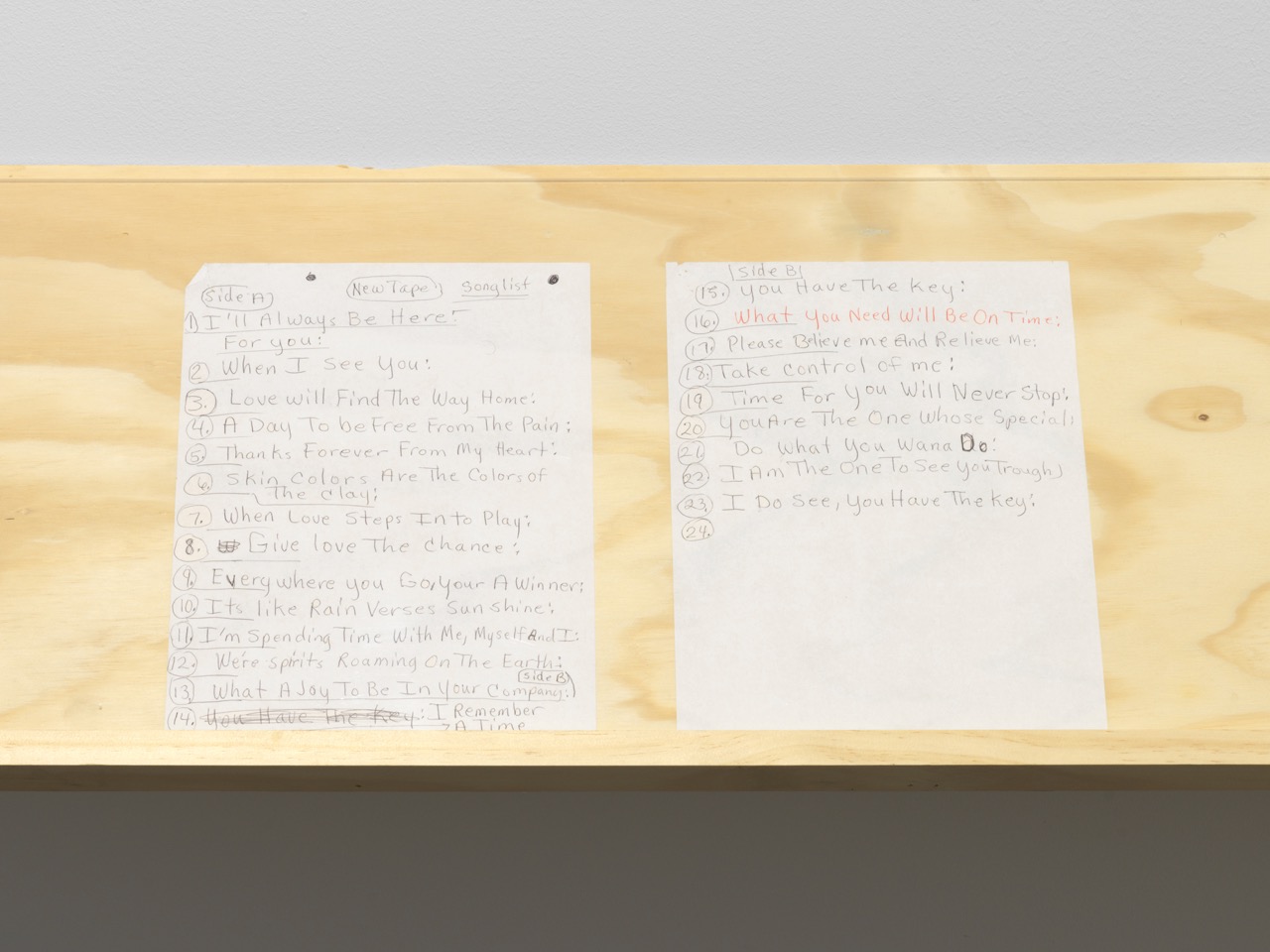

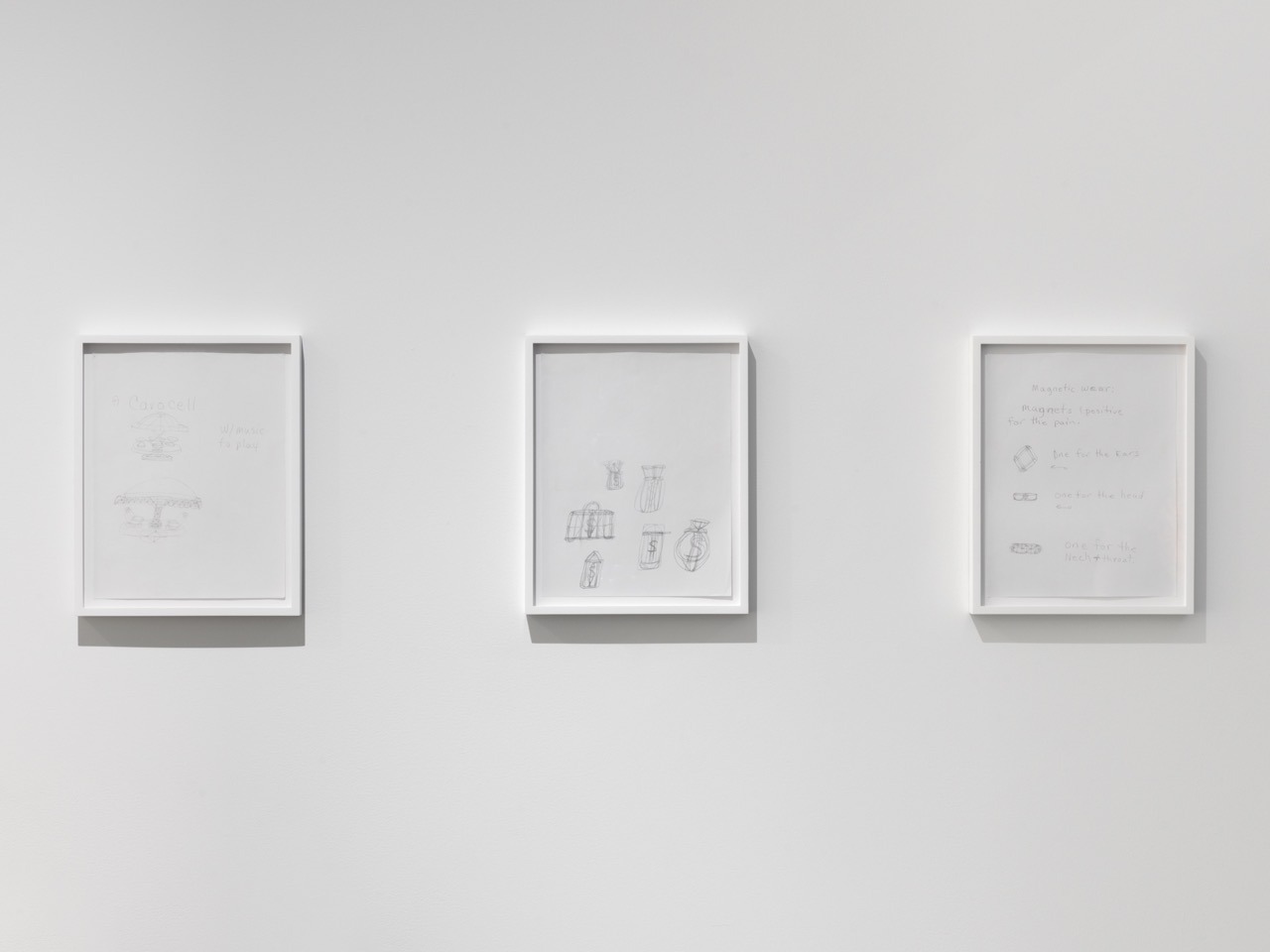

The brightly lit heart of Jacolby’s darkened exhibition space is an intimate room filled with Patricia’s work. Inside, he has provided a set of headphones through which you can hear her singing, and her handwritten lyrics are displayed on wooden ledges. Above, a line of pencil drawings—strange, annotated schematics for her inventions—encircles the gallery. Among the ideas proposed in her spare, often inscrutable sketches are poetic objects, such as a “a tea bag with a smile” and a “fake flower to stab in the ground or a pot,” as well as a concept for software that would “give the computer a choice,” she explains, about what to do with a “file that’s ended and saved,” including the option to delete it.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

Once apprised of Patricia’s solo output, it becomes easy, indeed unavoidable, to hear her voice and spot her hand in Jacolby’s work. PAT, named for her, features her disembodied vocals, digitized from her tapes, and reimagines her as a house diva—her words are plaintive and direct at times, transcendent at others, depersonalized through extreme filters or lush reverb. The barebones home recordings come alive, floating above or sinking into the duo’s dramatic electronic production; the tracks are beautifully severe compositions unfolding in dissonant, abstract passages and melancholic dance grooves. It’s not a stretch or an absurdist pairing—Patricia’s melodies work perfectly with PAT’s instrumentation, and, with lyrics like “there’s freedom in my house,” the music fits easily into a post-disco lineage of queer techno and sample-based experimentation.

A constant aural presence in her son’s baroque virtual-reality, simulated environments, she also contributes to them visually. Sometimes, when you look down while wearing one of the station’s VR headsets, her handwriting passes beneath you like a river in the completely immersive, panoramic, animated 3-D illusion. Her QVC fantasies appear as visitations, become strange structures, and then slip away. And some of them have been fabricated by Jacolby in real reality—not to become the functioning household gadgets that might find a mass market on TV, but 3-D printed as sculptural iterations of her diagrammatic works on paper, candy colored according to his aesthetic.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

Shrine for American Dream Designs (2019) is one of three multicolored wall displays holding such digital interpretations. Resting on the chic shelves, Patricia’s enchanting lacy armatures and blobby ornaments have the aura of both luxury retail goods and talismanic, devotional objects placed on an altar. Nearby, mass-produced items, such as T-shirts and lighters—customized the way a corporation might with its logo for promotional giveaways, but printed with her decidedly un-corporate drawings instead—have a similar, if diluted, presence as irresistible souvenirs. Everyday things, priced to sell, they represent one more way for the artist to realize his mother’s commercial ambition, and to reconcile her vision with his own.

Jacolby Satterwhite: You’re at home, installation view. © Dan Bradica.

I bought one of the lighters. It’s black, emblazoned in yellow with one of Patricia’s curious images—an uneven oblong, partially filled in with spaghetti-like lines—and, on the verso, lyrics, in her handwriting. “You’re At Home,” it reads. Homecoming in her son’s show is a fractured, tangled, and infinite journey through a thrilling and terrible galaxy, though he doesn’t hesitate to divulge the paradoxical secret. It’s right there in his (his mom’s) title. You’ve already arrived, you’re always arriving, and you never really left after all.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.