Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

A mid-career retrospective presents the artist’s ongoing quest to push boundaries from a first-person perspective.

Hemlock Forest. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

“Moyra Davey,” organized by Sophie Cavoulacos, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through October 10, 2022

• • •

Risk is a defining artistic value for Moyra Davey, its absence a hallmark of mediocrity. The New York artist—she is known as a photographer and a writer as well as a filmmaker—alludes to this principle more than once throughout the eleven films, which span 1990 to this year, screening in her mid-career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. (The program begins tonight, September 23, with the New York premiere of her latest, feature-length work, Horse Opera.) In the voice-over at the start of her 2016 Hemlock Forest, a searching and distraught, formally riveting paean to Chantal Akerman, who died by suicide the previous year, Davey says—or rather intones, carefully, haltingly, as is her custom—that she placed a camera on her dashboard to capture the treetops along the Palisades Parkway. (Presumably, this is the greenery and bright sky we see as she speaks.) When Davey glanced at the small screen while driving, “the shots seemed promising,” she recounts, “but when I looked at them later, they were absolutely ordinary. I call this type of filming ‘low-hanging fruit’ and it rarely adds up to much, because so little is at stake.”

Hemlock Forest. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

To begin with the announcement of a problem, the illumination of a doubt—by pointing out a potential weakness of the very material she presents—is perhaps quintessential Davey. The palpable sense of daring that infuses her precariously, digressively structured films is born of personal exposure; she has explored, from a candid first-person perspective, such topics as motherhood, her relationship with her psychoanalyst, a difficult family history, and illness. (She sustains this intimate tenor, hanging on to a diaristic mode, even when her subjects are not autobiographical—the letters of Mary Wollstonecraft, a window view of Walter Benjamin’s, the animal portraits of Peter Hujar, or a particular passage by Jean Genet, for example.) But there’s also an unsettling tension, an air of danger, produced by her restless self-reflexive commentary, an existential meta-discourse always quietly debating whether or not to pull the plug on the whole affair. Perhaps because Davey began as a photographer, and because writing is fundamental, not ancillary, to her practice, filmmaking feels like a provisional solution, a way to facilitate a convergence of impulses, visual and literary—good enough for now.

Fifty Minutes. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

Her body of moving-image work is united foremost by her voice, the elocutionary anti-aesthetic that marks her narration as text more than speech. In most of these films, we see her pacing, often at length, back and forth in an untidied domestic space as she reads or recites her script. In Fifty Minutes (2006), close-ups of Davey speaking directly into the camera are alternated with wider shots of a cramped Manhattan apartment in which she wanders through the frame or stands swaying at its edge. She has a similar ambulatory, slightly spectral presence some fifteen years later, in Horse Opera, though its pastoral backdrop (Davey’s home in Sullivan County, New York) refracts her signature interiority differently. Moving around lends her rumination a somatic dimension, and the confined settings for such scenes—with their dusty specificity, humble furnishings, photographs, and worn books—anchor everything in one, very particular, real life.

Horse Opera. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

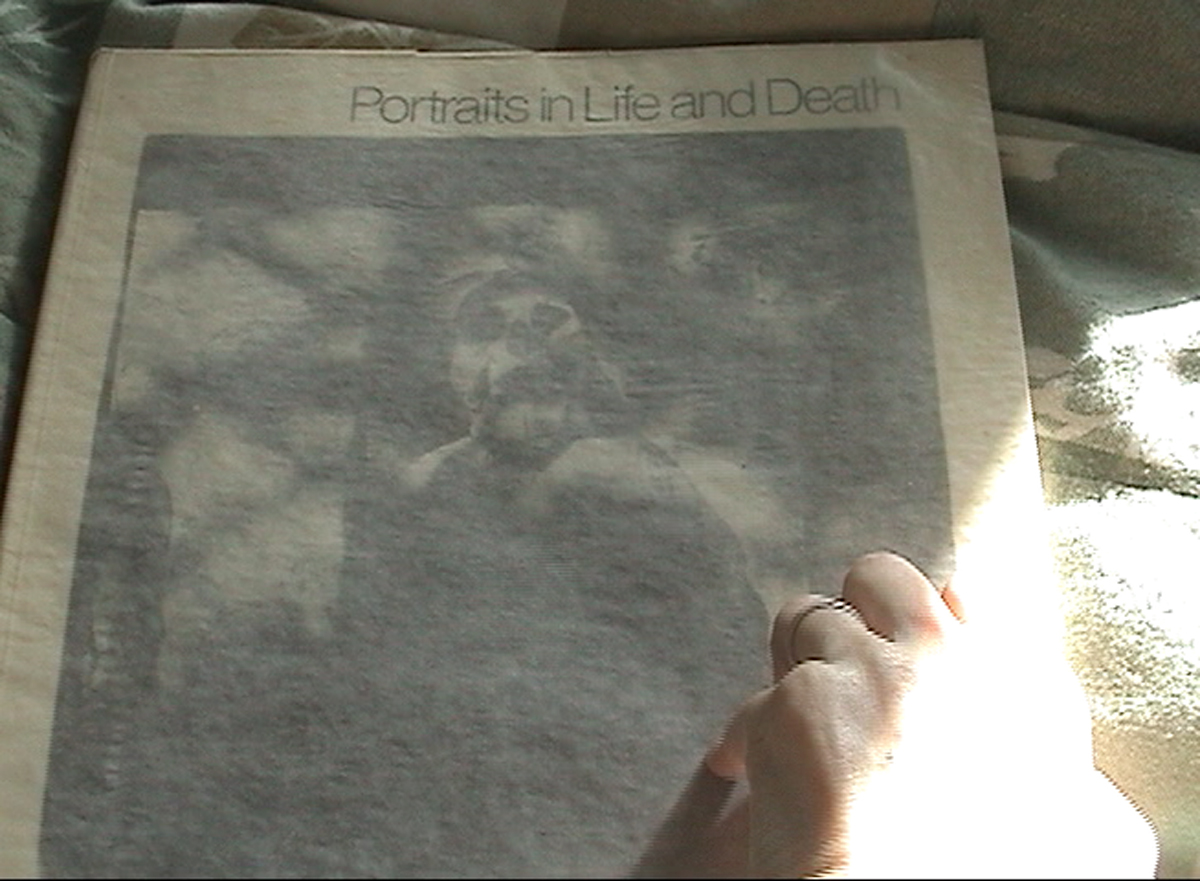

Her enduring fascinations provide other through lines. Images, quotations, gestures, and anecdotes echo and overlap as Davey circles back to what haunts her, unresolved. Window vantages evoke longing and introspection; views of hands turning pages from above—beloved books, her own photo albums, and, in the uncharacteristically silent, four-minute Hujar/Palermo (2010), the pages of the deceased photographer’s remarkable 1976 volume Portraits of Life and Death—underscore Davey’s passion for reading and looking, as well as her interest in the drama or banality of the smallest actions.

Hujar/Palermo. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

Of course, over more than three decades, much has changed; Davey always tries—risks—something new. It’s the tenacity of her sensibility, though, that’s most striking when viewing her films as a group. Her first film, the Super 8 short Hell Notes (1990/2017), made with a camera on loan from the filmmaker Jennifer Montgomery, would seem something of an outlier, with its more self-conscious staging of vignettes, relatively animated voice-over, and impersonal subject matter (the geological substrate, built environment, and New York City landmarks; the Freudian equation of money with shit). But, in retrospect, its lingering shots (the artist remarks, in the program notes, that she came to view the film as a “love letter” to the metropolis) prefigure the urban vistas and idiosyncratic detail of her later films. At MoMA, Hell Notes will be shown with John Cassavetes’s action-thriller Gloria (1980), which impressed Davey with its similarly “granular” depiction of Manhattan. It has a more sentimental significance to the artist, too: Gloria’s protagonist, played by Gena Rowlands, flees to Washington Heights, to Davey’s own apartment building—an apt extension of how the artist uses serendipitous relationships in her work, preferring them sometimes to scholarly or formal bridges between subjects. (For the retrospective, Davey has paired several other of her films with works that have served as personal touchstones.)

Les Goddesses. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

In Hemlock Forest, Davey revisits her thematically and emotionally related Les Goddesses (2011), confessing, or simply explaining, that for Les Goddesses she “forged a coincidence of dates, two hundred years apart, to make connections and enable a story.” In that earlier, transfixing documentary-memoir, the radicalism, brilliance, and tragic experiences of Wollstonecraft, her daughters Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, and their circle of intimates become an imperfect mirror—a sharpening prism as well as a distancing device—for the troubled teenage years (and beyond) of Davey and her own sisters. Gratefully citing the artist Iman Issa’s astute observation about the role of the first-person in Les Goddesses, the filmmaker claims “the desperate ‘I’ of last resort” employed in that film once again for Hemlock Forest.

Les Goddesses. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

It is an anxiously elegiac work, strangely energized by mourning, and stands out (with Les Goddesses) as one of my favorites. Davey dwells on Akerman’s own experiments, reproducing, or approximating, some of the legendary director’s most remarkable scenes as she corrals a range of abbreviated meditations on far-flung, mostly literary, subjects into the video’s forty-one minutes. Davey fixates on cinematographer Babette Mangolte’s shot of the 1 train in Akerman’s News from Home (1977), a film composed (a bit like Hell Notes) of long takes of Manhattan, accompanied by voice-over (like so much of Davey’s oeuvre is). Unlike the aforementioned, makeshift dashcam footage of trees, Mangolte’s camerawork is, for Davey, the “opposite of low-hanging fruit.” She’s awed by its beauty and its technical difficulty, as well as the public bravery required to intrude into people’s space. She pushes herself to stage a contemporary version. She also reenacts a scene from Akerman’s Je Tu Il Elle (1974), when Julie, played by the filmmaker herself, eats sugar from a bag, partially undressed on the bed. Davey’s sunlit shots are similarly beautiful, jarring at first for their depiction of fake voraciousness or real compulsion.

Hemlock Forest. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz.

There’s a weird tranquility to the scene; it offers a break from language after a while. Amid Davey’s alternately deliberate and feverish arrangement of elements—fleshed-out ideas alongside unmoored fragments, synthesized somewhat but never safely smoothed out—it’s a chance, following her lead, to step out of her head.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum.