Elvia Wilk

Elvia Wilk

The poetry of potential: Quinn Latimer’s group show translates the Siren’s call into a multisensory experience.

Jenna Sutela, nimiia cétiï, 2018 (still). HD video. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

SIREN (some poetics), curated by Quinn Latimer, Amant, 315 Maujer Street, Brooklyn, through March 5, 2023

• • •

Greek antiquity is full of women with threatening, disturbing, or unruly voices. The hideous Gorgons, Medusa and her sisters, whose gruesome howls are as terrifying as their visages; the ritual mourners, whose public shrieks—moirologia—expressed the inarticulable pain of social loss; and, famously, the Sirens, whose bewitching song lured sailors to dramatic deaths on rocky cliffs. In Homer’s epic, Odysseus instructs his men to lash him to the mast of his ship so that when they approach the Sirens he can hear but not steer. He just has to hear the captivating song—but he refuses to be overtaken by its force. How manly of him.

In a curatorial text introducing her group exhibition at Amant, SIREN (some poetics), critic and poet Quinn Latimer points out that in The Odyssey, Homer doesn’t describe the Sirens’ bodies; only in later translations and art were the creatures depicted as woman-fish or woman-bird amalgamations. It is the disembodied, eerie, seductive, not-quite-human voice that serves as a guiding logic—or illogic—for Latimer’s show, in which she aims to avoid the “cool, clinical, conceptual” methodology of typical exhibits dealing with language and poetics. But avoiding the rocks is one thing; navigating by the stars is another. Not only does SIREN reject the sterility (and pretension) of a certain literary-artistic tradition—words on a page, words on a wall—I found it produces a profoundly sensual experience in which reading, looking, listening, and moving become one.

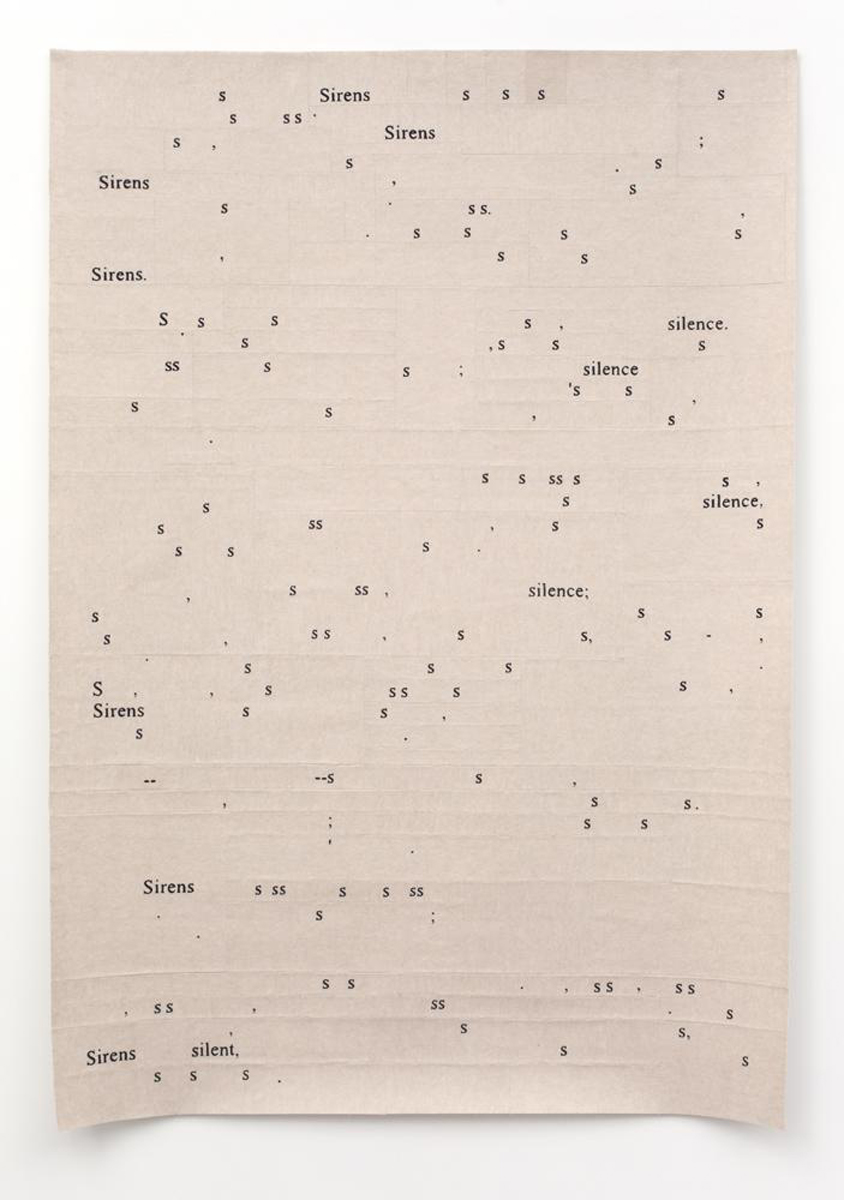

Rivane Neuenschwander, The Silence of the Sirens, 2013. Felt, thread, fusible interfacing, D-ring metal, 51 1/8 × 73 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

A siren, in its current English usage, signals alarm and warns listeners to take safety precautions—a curious inversion of the mythical Siren who commands auto-destruction. “It wasn’t a sound to call you in, it was a sound to push you away,” says the narrator of Aura Satz’s 2018 film Preemptive Listening (part 1: The Fork in the Road), projected in the largest of Amant’s four spaces. That narrator is artist and activist Khalid Abdalla, who recalls hearing emergency sirens in Egypt during the Arab Spring. Although the noise conjured distress, Abdalla also remarks that it now signifies to him a “fork in the road”—a point at which the future might have gone differently, maybe toward liberation. The siren is an injunction to decisive action (stay or flee), but what if urgency could be suspended, time stretched? Instead of panic, is it possible to pause and listen? If we know what danger sounds like, what might be the sound of resistance?

Aura Satz, Preemptive Listening (part 1: The Fork in the Road), 2018 (still). Film, color, stereo, 8 minutes 47 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

Social transgressions trigger alarm. In another space, the duo Shanzhai Lyric have arranged six tall alarm systems in a circle, the kind of armatures you find at store entrances that blare when someone shoplifts (Untitled (Portrait of a Siren), 2022). The artists modified the startling sounds to produce a strange electronic chorus, and elsewhere in the exhibition space viewers can pick up anti-theft tags to set off the alarms themselves. Dozens of T-shirts hang on nearby racks: Shanzhai Lyric is known for these assemblages of imported or counterfeit clothing emblazoned with mistranslated English slogans or brand names that read as incredible ad-hoc poetry. SOUND BITES / FOR YOUR EYES and TMOYM HIFILG read two in their collection. Despite textual claims to authority, the idea of “original” material is counter to Western tradition; The Odyssey itself is a translated version of a bastardized transcript of an oral epic. Languages, any linguist will tell you, are not static in time, and as poet Anne Carson will tell you, “languages are not sciences of one another.” As much as it purports to expose meaning, language also obscures and therefore safeguards it, through forms of untranslatability and illegibility.

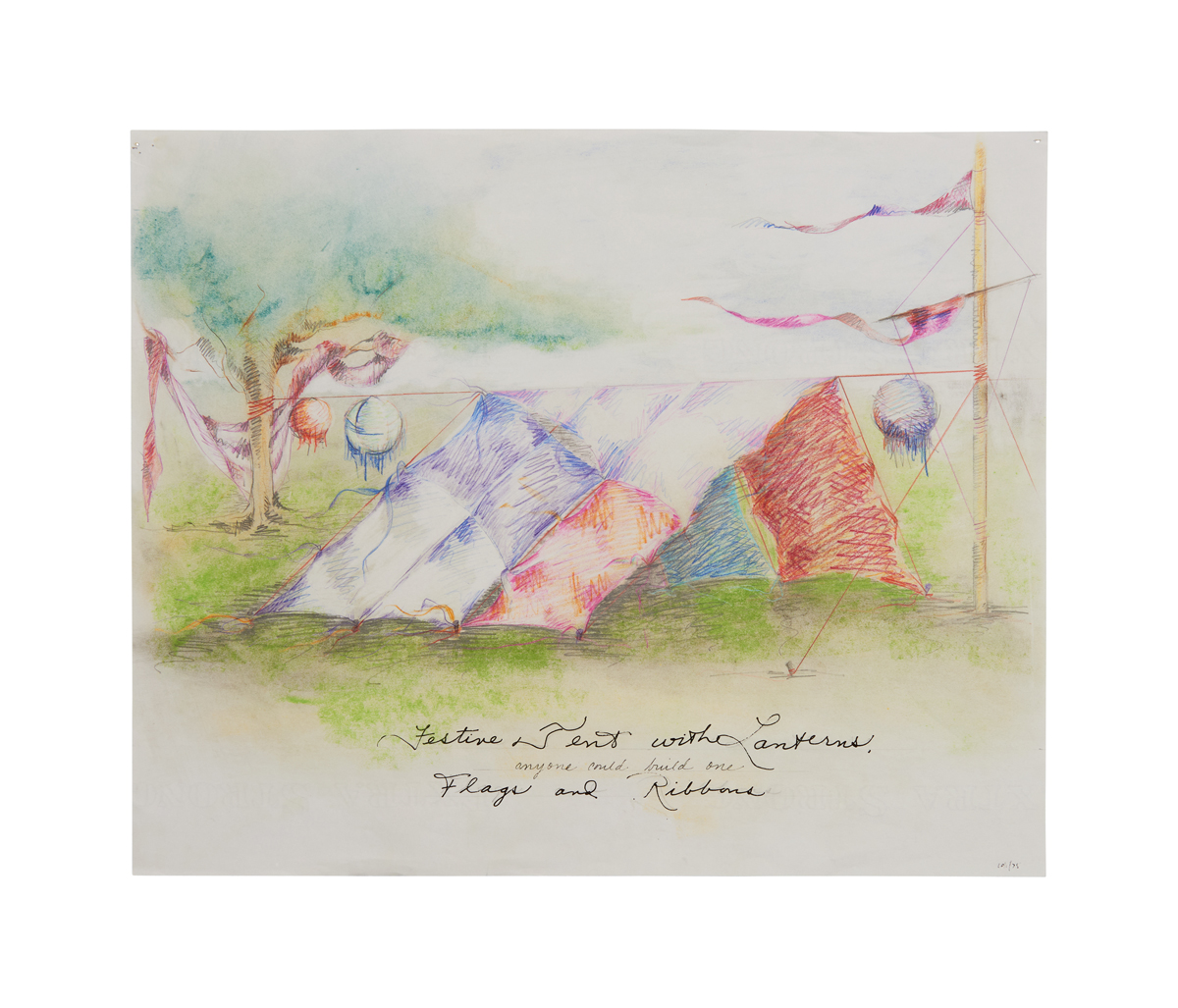

Rosemary Mayer, Festive Tent with Lanterns, 1975. Colored pencil and pastel on paper, 14 1/2 × 17 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

Garment, sail, tent, banner. Fabric would be overtly missing in any show derived from a Greek epic, in which storytelling and weaving, texts and textiles, are sisters (Penelope’s story twins Odysseus’s, but while he forges ahead she undoes her narrative threads each night). Draped and hanging cloths recur, for instance, in many displayed drawings by Rosemary Mayer, who, in the 1970s and early ’80s, often sketched—and, in one case, built—tents to host moon rituals loosely based on practices from antiquity. These lyrical, gleeful drawings of fluttering fabrics inscribed with her handwriting, like Festive Tent with Lanterns (1975), serve as both imaginary conjectures and plans for action.

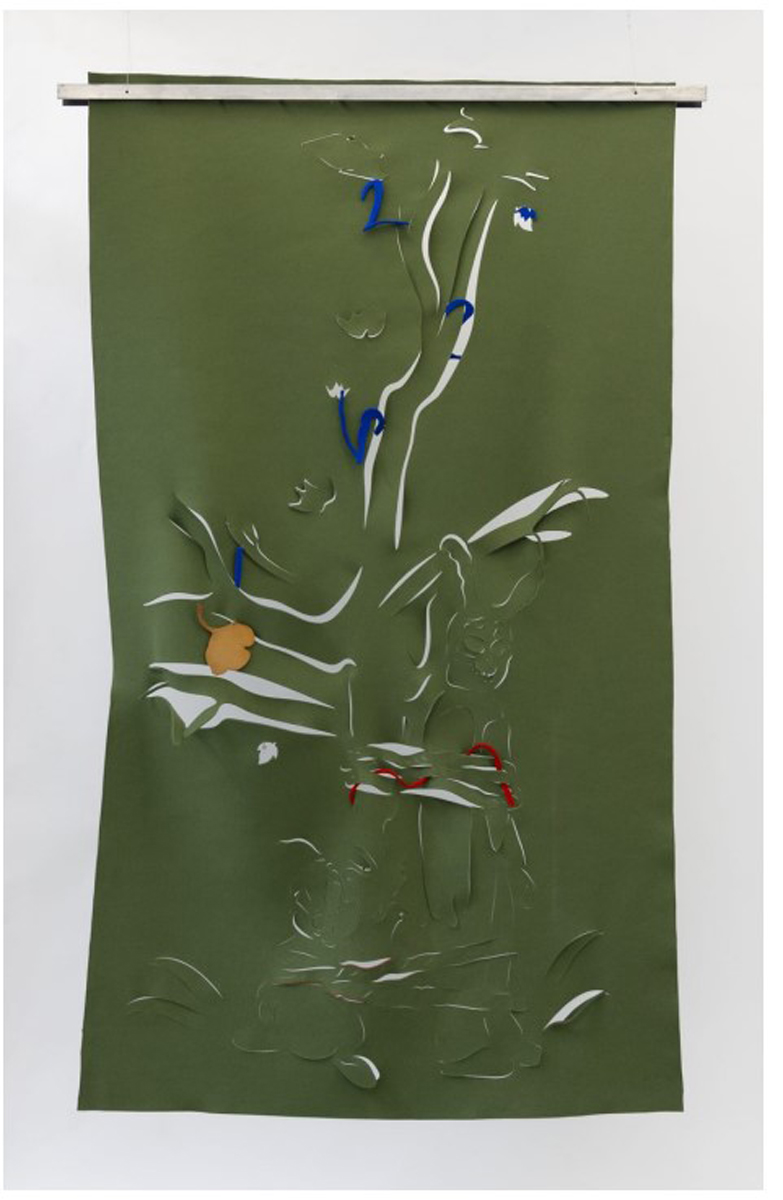

Dena Yago, Rope and Lead, 2018. Pressed wool, hand embroidery, pewter charms, steel, 105 × 57 × 2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

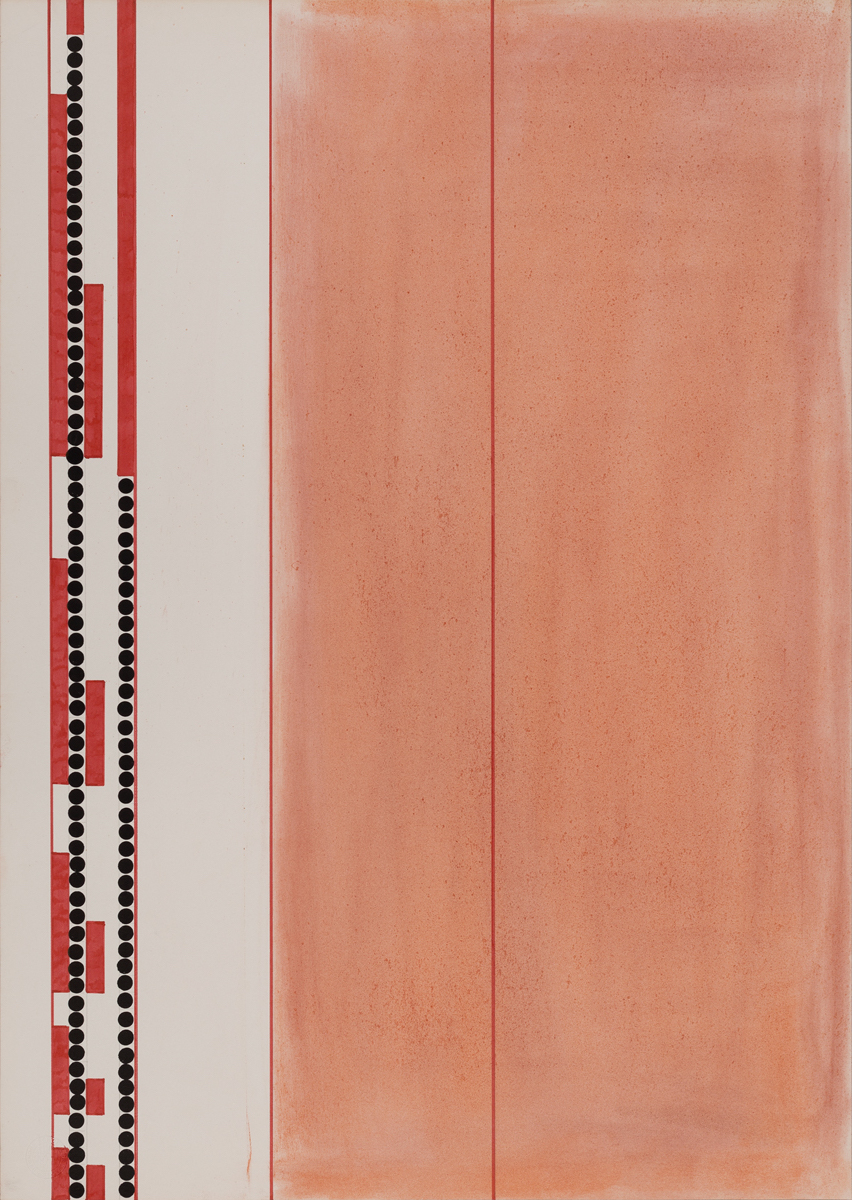

As if extrapolated from Mayer’s drawings, installed in a smaller room are Bia Davou’s majestic linen sails. Untitled (Odyssey) (1980s) are swooping geometric shapes stretched between ceiling and floor, on which fragments of language (including lines from The Odyssey) are stitched and drawn. Dena Yago’s Rope and Lead (2018) is a green wool hanging banner that’s been slashed and pierced with delicate metal charms, as if to ward off calamity; Rivane Neuenschwander’s The Silence of the Sirens (2013) is a muted pinkish felt tapestry embroidered with words and letters resembling concrete poetry—more spaces than letters.

Katja Aufleger, Sirens (Al Wakra Vol. III), 2019. Seven glass organ pipes, engine, wood, silicone hose, aluminum. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

Odysseus, seeing no Siren bodies, may well have believed the landscape itself was calling to him, and fittingly, Latimer has invited the voice of the nonhuman world into the chorus. Katja Aufleger’s 2019 Condition 7.3 5pm (Al Wakra) is a silent video of sand dunes in the Qatari desert that are known to “sing” as the wind slides over them; the viewer watches drifting sand, like particulate evidence of sound waves. Across the room another of Aufleger’s works (Sirens (Al Wakra Vol. III), 2019) provides the sonic component to the image. Air pumped through seven tubular glass instruments (glass: compressed sand) approximates the tones of the dunes. Eerie organic-machinic voices emanate from two videos by Jenna Sutela; one, nimiia cétiï (2018), features an algorithmic interpretation of a “Martian” language originally channeled in tongues by the nineteenth-century spiritualist Hélène Smith. And in Nour Mobarak’s Fugue I and Fugue II (both 2019) the human communicates through a nonhuman medium: four speakers held in vessels made from Trametes versicolor mushrooms play conversations between the artist and her father as well as Mobarak singing a cappella.

Nour Mobarak, Fugue II, 2019. Trametes versicolor, wood pellets, two speakers. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

For a group show curated by a poet, with a title referencing an epic poem, with the subtitle (some poetics), one might expect text all over the place. Yes, there are letters and captions and handwriting to be found (as in Sky Hopinka’s lovely script scrawled over landscape photographs, or Iris Touliatou’s charming tiny screen displaying spammy email subject lines, or Bernadette Mayer’s color-coded poems adhered to the walls), but the show excels in its attention to the mysterious gaps between mark-making and writing, between sound and language. My attention snagged on Davou’s four Untitled works on paper (1974–78), which look like mysterious diagrams, constellations, or musical scores—while puzzling over them, I could hear the low tone of Aufleger’s wind instruments under the melodic soundtrack from Hopinka’s Fainting Spells (2018), with intermittent bits of monologue from Satz’s film.

Bia Davou, Untitled, 1974–78. Ink, pencil, dry pastel on watercolor paper. Courtesy Radio Athènes and Melas Martinos.

The best thing that can happen to me while reading a poem is to fall off a cliff at a line break. In the plummet, meaning splits apart, and when I land on the next line (or in empty space!) I can’t retrace my steps. This gap in the sensible that poetry provides is pure potential: aesthetic and political. Such eruptions in time and meaning—like the femme voices of Greek myth—threaten order and containment. SIREN translates these tiny, solo epiphanies of reading into physical, social space. No artificial cohesion has been enforced, no top-down epic narrative exerted, but harmonies and resonances have been found, creating polyphony. The curatorial sensibility is flexible without being flimsy, like a sail oscillating between laxity and tension as air puffs and subsides—as wind inhales and exhales, carrying voices on the edge of translatability.

Elvia Wilk is a writer living in New York. She is the author of the novel Oval and a book of essays called Death by Landscape. Her work has appeared in publications like frieze, Artforum, Bookforum, the Atlantic, Granta, the Paris Review Daily, the Baffler, n+1, the White Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is currently a contributing editor at e-flux Journal.