Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

More muchness from the experimental Venezuelan musician.

Arca. Photo: Unax LaFuente. Courtesy XL Recordings.

KiCk I, KICK ii, KicK iii, kick iiii, kiCK iiiii, Arca, XL Recordings

• • •

Arca is flying into the tenth year of a hot streak, thirty tabs open, receptive to crisis and friendly with mourning. After averaging an hour of recorded music a year since 2012, she upped her production levels and released five albums (and one EP) in eighteen months, four of them in the last two weeks. KiCk I came out in June of 2020, and then four more volumes—rendered as ii, iii, iiii, and iiiii—were burped out in December. That’s three hours of music and it is, in every sense, a lot.

Arca makes her music primarily with software and piano and her voice, and then throws it, blades out, through reggaeton, dembow, dance variants, rap, verses, choruses, interludes, drones, tonada. That last approach is a lament originally sung by cowboys and herders. In 2018, Arca talked to me about tonada and Simón Díaz. She called “Caballo Viejo” “one of the most famous sad songs in Venezuela,” and it was the Díaz version she heard first.

When she was seventeen, in Caracas, Arca connected with the song and the “sorrow that couldn’t fit into one body.” Díaz was the host of Contesta por Tío Simón, a TV show for children, which represented “a split in him that I related to.” Díaz sang at the top of his throat with a “really gentle falsetto” and a “sternness” from the chest. She recognized this approach to singing because “I just split it up and create myself so many times, that I can literally pinpoint where my voice is coming from in my body.”

Arca. Photo: Unax LaFuente. Courtesy XL Recordings.

Splitting, muchness, sorrow, and the body are variables to track with Arca. If you’re just starting with her music, try a short and largely instrumental album from 2013 called &&&&&. Arca runs a whole tarot deck through her production matrix and fires a bunch of quick chops and independent loops down a narrow, empty well. Grime beats, player pianos, video-game sounds, and crunched field recordings are all ballpoint pens between the fingers of a bored teen. Then on Arca, her 2017 album, you get something close to pure tonada. Arca is deeply felt and unpredictable, sung almost entirely in Spanish and framed in furry bass and canine whistles. There’s also Utopia, the full-length album she made with Björk in the very same year, and best described as a series of duets, rather than Arca producing Björk songs. Then there is @@@@@, the hour-long “single” that Arca released in February of 2020 before the KiCk series began. Yes—she can think of sixty-two minutes as a single.

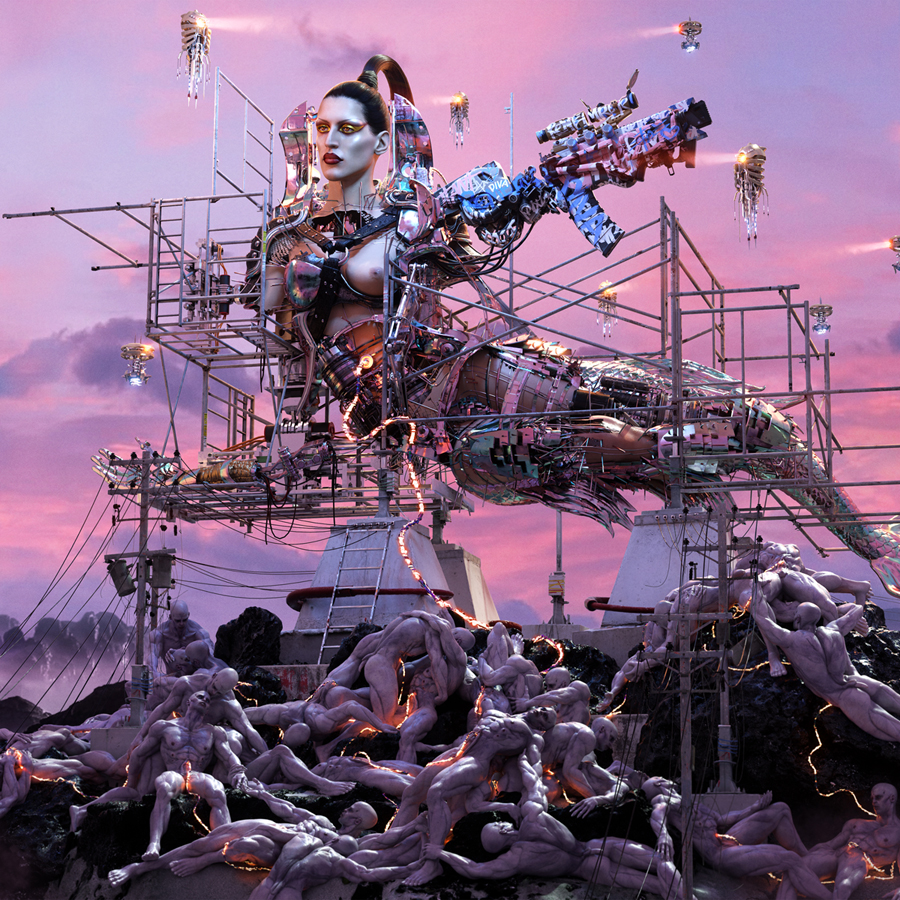

kiCK iiiii album cover. Courtesy XL Recordings.

Her visuals begin and end with her body. Or the body, in general, as seen in the art generated over the years by Jesse Kanda for Arca’s releases. A kind of template for her cover figure developed, a mammalian shape rendered in smooth, translucent skin piled up in folds, like genitals given a personality and a royal appointment. Now, working in gothic nightmare mode with Frederik Heyman, Arca is producing videos that threaten to dwarf the albums. On Instagram, in November, she presented thoughts about the song “Prada” as captions for screen caps from that video. “Prada” is about “transness and nonbinary modes of relating the sexual energy of the collective subconscious as a celebration of life” as well as “kink as an engine” and many other things. In relation to her song “Rakata,” she mentions “the hot and humid conditions that birthed latinx music,” specifically “regeton royalty wisin y yandel,” as well as “venezuelan folklore, life and eroticism birthed near the heat of the equator.” I quote this at length as evidence of her muchness and the vast ambitions of her project. In the video, through digital manipulation, Arca is seen riding a horse-hog beast and then being milked by six metal suction cups while her mechanical wing-arms delicately hold pieces of flesh that may or may not have been taken from some of the flayed bodies hung upside down in a circle around her. Rock and roll!

kick iiii album cover. Courtesy XL Recordings.

Arca has always been extremely online and available. She started in the 2000s with forums and then moved into Instagram and other spots. Now, Arca maintains a trans-friendly Discord channel that feels like its own municipality. There are fifteen fruit and vegetable emojis proposed as corresponding visuals for different sexualities, and the conversation tends toward chaotic selfies and mutually supportive talk about sex and life. If, reasonably, somebody is put off by the dismantled bodies and skeletons in Arca videos, they might prefer her Discord, a warm and utopian homeroom. The last time I checked in, members were posting advice on dating for the first time and picking favorite tracks from each album. Who wouldn’t want their kid in that kind of community?

KicK iii album cover. Courtesy XL Recordings.

I’ve been listening to all five KiCks as a shuffling playlist and it is a little like being swallowed by a friendly whale on stimulants. The absence of fear is often signaled by chunks of disobedient noise, silver flags waved at the easily startled in the crowd. As she says—and she does this just by speaking, not singing—in “Nonbinary” from KiCk I, “I don’t give a fuck what you think.” It’s an easy boast that sounds new in her mouth.

There is plenty of that exquisite ache from Arca on songs like “No Queda Nada” (KiCk I), and illogical, blinking noise on songs like “Femme” (an instrumental from KICK ii) and “Crown” (from kiCK iiiii). “Fireprayer” from iiiii is a bit like a hair-metal ballad with the voices taken out and Cecil Taylor taped to the end of it. “Rubberneck” from iii sounds like someone playing pattycake on a weather vane and rapping nonsense.

KICK ii album cover. Courtesy XL Recordings.

This music is full of decisions that make Arca’s style more important than your ease. A month inside the KiCks changed my perception of how songs move. Arca is not generally interested in pieces that resolve like a chart hit. She is committed to useful chaos—in particular, the overload of mixtapes, where the surfeit of beats makes you feel worked over, palpated, a human afloat on the effort of machines. This is where “Rakata” (KICK ii) sits, a crackly riff on the internal motion of reggaeton. When Arca relaxes her grip, the sound shifts into something between the tonada and late-nineteenth-century classical music. “Lost Woman Found” reflects Arca’s proximity to Björk, and also to a tradition of European piano music.

These are Arca’s bunkers, the poles of her travels. A big chunk of the KiCks music summons either an off-the-grid dance space, littered with rebar and dirt and demobbed military gear, or the ballroom of a decaying family home. A holographic teleportation of an agile mobile robot into the manse: RoboCop meets Grey Gardens. There is violence and grace in Arca’s music and little room for a midpoint that might feel comfortable for an outsider. Arca’s kind of kick represents investment and responsibility both, the bind of permission.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.