Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

The burning charm of Etel Adnan’s prose and poetry in a

comprehensive collection.

To look at the sea is to become what one is: An Etel Adnan Reader, by Etel Adnan, edited by Thom Donovan and Brandon Shimoda, Nightboat, 747 pages, $34.95

• • •

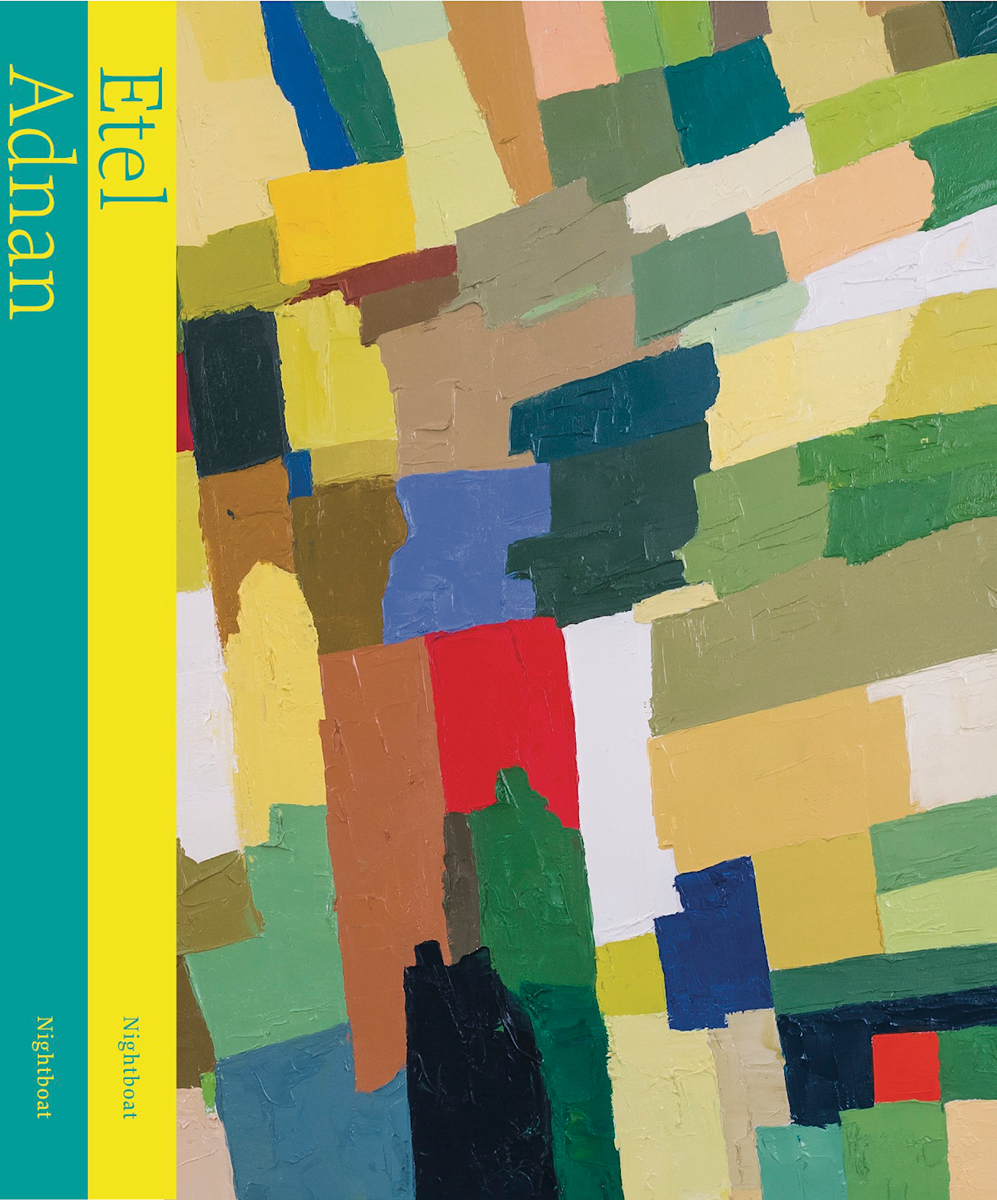

Born in Beirut in 1925, Etel Adnan worked in the light for almost seventy years as both a writer and painter. In the last decade, though, her visual art has received the lion’s share of attention. In 2012, at Documenta 13, Roberta Smith called Adnan’s work “stubbornly radiant,” and her oil paintings found an international audience. Adnan’s Guggenheim retrospective, Light’s New Measure, opened in October, just a month before her death in November at the age of ninety-six. Part of a cohort, with painters like Samia Halaby, that the critic Kaleem Hawa calls “Levantine abstraction,” Adnan was prolific to the last. Her paintings are a juggling of chunky familiarities—plenty of circles and rectangles—but her hot shapes are not actually so abstract. Adnan was representing suns and mountains and hills, including Mount Tamalpais, all of which she could see from her desk in Marin County.

My love for Adnan began with her writing, and a different sense of place. Twenty years ago, I found Paris, When It’s Naked, a short book from 1993 that weaves the steel braid of her charm around the practical challenges of living with others. She tells us that “cities attract each other like flowers do,” and threads Paris and Aleppo and Beirut together. But she is not of every city, and only ventures out when her “official papers” are “resting in their drawers.” Here, as in all of her poetry and prose, Adnan does not shave her subjects down into the docile totems that might make her universal view more of a tonic. Adnan’s connections burn rather than soothe, and now is a good time to revisit her world tour. Nightboat is releasing a new edition of To look at the sea is to become what one is, a comprehensive collection that contains everything mentioned here (either in full or in excerpts). Litmus has also issued a new version of a 1986 essay, Journey to Mount Tamalpais, with some additional ink drawings.

Born to a Greek Orthodox mother and Syrian Muslim father, Adnan, who had to drop out of school as a teen to work, ended up studying poetry in Beirut, aesthetics in Paris, and philosophy in Berkeley, before ending up in San Rafael to teach. In Northern California, she discovered a community of experimental writers and practiced her English by listening to San Francisco Giants games on the radio. Adnan only started painting in 1959, when she was encouraged by her colleague Ann O’Hanlon to ignore her mother’s judgement that Adnan was “clumsy.” Resenting having to express herself in French in the midst of the Algerian war, she resolved to “paint in Arabic.”

Adnan spoke Greek and Turkish at home, Arabic in the street, but the nuns at her school in Lebanon tolerated only French. She wrote in French and eventually English, and her arguably best-known work is Sitt Marie-Rose, published in French in 1978, and then issued in English by her partner Simone Fattal’s Post-Apollo press. Adnan recasts the story of Marie Rose Boulos, a Syrian immigrant who taught deaf-mute children in Palestinian camps and was executed by the Christian militia. The book is a kaleidoscopic blend of viewpoints: the soldiers, Sitt Marie-Rose, a writer who could be Adnan, and the children.

The teacher is abducted: “Nothing moved in the street except my captors. Everything seemed staged including the short flight of a bee from one tree to another. They said: ‘We’ve got to talk to you.’ And I understood that, with those words, I was leaving the world of ordinary speech.” Marie-Rose’s captor, Mounir, fell in love with her when they were in high school. Mounir’s fellow soldier, Tony, has no such attachment. “She’s Lebanese and she went over to the Palestinian camp. Where’s the problem? We must do away with her like with every other enemy.”

After the children watch an Egyptian movie, The Sparrow, with Marie-Rose, they speak in first-person plural about how people embody class in films. “We’re not all poor. It’s not enough just to be poor to be The People. You have to be docile and innocent. You have to be a part of things like clouds are a part of the sky.” Marie-Rose is quartered in front of her students, and the poet tells us, “whether you like it or not, an execution is always a celebration.” The kids get up and dance, “moved by the rhythm of falling bombs their bodies receive from the trembling earth.”

Adnan’s prose is easily understood but doesn’t dry out in the heat of what it faces. As her colleague Brandon Shimoda wrote, he came to “think of Etel as elemental, as water,” an artist for whom “every perception is still wet.” In the same way that Sitt Marie-Rose is only a novel because that noun can index all of the book’s pieces, Journey to Mount Tamalpais (written in English) is an essay simply because it isn’t broken into metric lines, and could also be called a memoir. “Once I was asked in front of a television camera: ‘Who is the most important person you ever met?’ and I remember answering: ‘A mountain.’ ” Adnan lives with the mountain, walks around it, sees it from the road, and begins to blend her life into her experience of the mountain.

She hears a tape of George Jackson recorded while he was still in prison. His “voice slides between his lips, and his longest word, his most important one, the one pronounced with a long, burning, agonizing, pleading, and ever sure voice, is the word love.” She watches televisions and sees Vietnamese convicts who had been turned into infiltrators by the US Army. (Her first English-language poems, published in 1966, are told from the viewpoint of Viet Cong soldiers, though here Adnan narrates from her own perspective.) “There was an ugly happiness on their faces, a determination to stay alive at any cost, that sent shivers along my spine. Isn’t perception always redefining Evil?” Adnan’s morality is woven into every sentence, no different from any other angle insofar as no experience escapes being both natural and political. She considers autumn, and “in such days leaves fall as young men in war, softly, carrying a lingering life around them.”

As she told Shimoda in August of 2012, “I grew up in a Lebanon with no books in the homes, no archives on people’s minds, no hierarchy of any sort.” Her writing feels like Gospel in its nimble, unscared density, and also in her suggestion that our commitment to others begins when we find ourselves together in the same place. Scale is the enemy of the good in Adnan’s world. As she describes a night at home in her final book, a short prose volume from 2020 called Shifting the Silence, “a simple dinner in a simply friendly atmosphère, moments stolen, mysterious, given the weight of the air that we’re breathing.”

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.