Tim Griffin

Tim Griffin

The pioneering artist’s work continues to challenge notions of power and aesthetic value.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., installation view. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., organized by James Rondeau and Robyn Farrell, Art Institute of Chicago, 111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, through January 24, 2022

• • •

Almost by definition, an artist’s career survey is bound to parse that individual’s production into different periods, each signaled through the deft selection of pivotal works, in order to craft a convincing narrative that ultimately burnishes a legacy. Yet it should come as no surprise to viewers that Barbara Kruger’s Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. at the Art Institute of Chicago—featuring nearly eighty works by the artist made over the past forty years—doesn’t adhere to that model at all. On the contrary, the exhibition is clearly designed to undercut readymade notions of both historical progression and artistic authority.

And how else could it be? Kruger was writing by the 1980s that the very conception of history needed to be recast to allow for discontinuities and difference. In the artist’s amazing “Remote Control” column that ran in Artforum during that decade, she also decried the aptitude of media outlets—from magazines to network news—for making events in culture seem as incontrovertible as nature. And Kruger has long turned the design language of mass media upon itself precisely to disrupt and dispel such naturalizing mythologies. So it is that Thinking of You displays a tactical brilliance with respect to mapping Kruger’s own practice, utilizing the premise of the survey only to problematize it—and to prompt a more nuanced awareness of the unsettled terms for artistic engagement within our current social context, in turn.

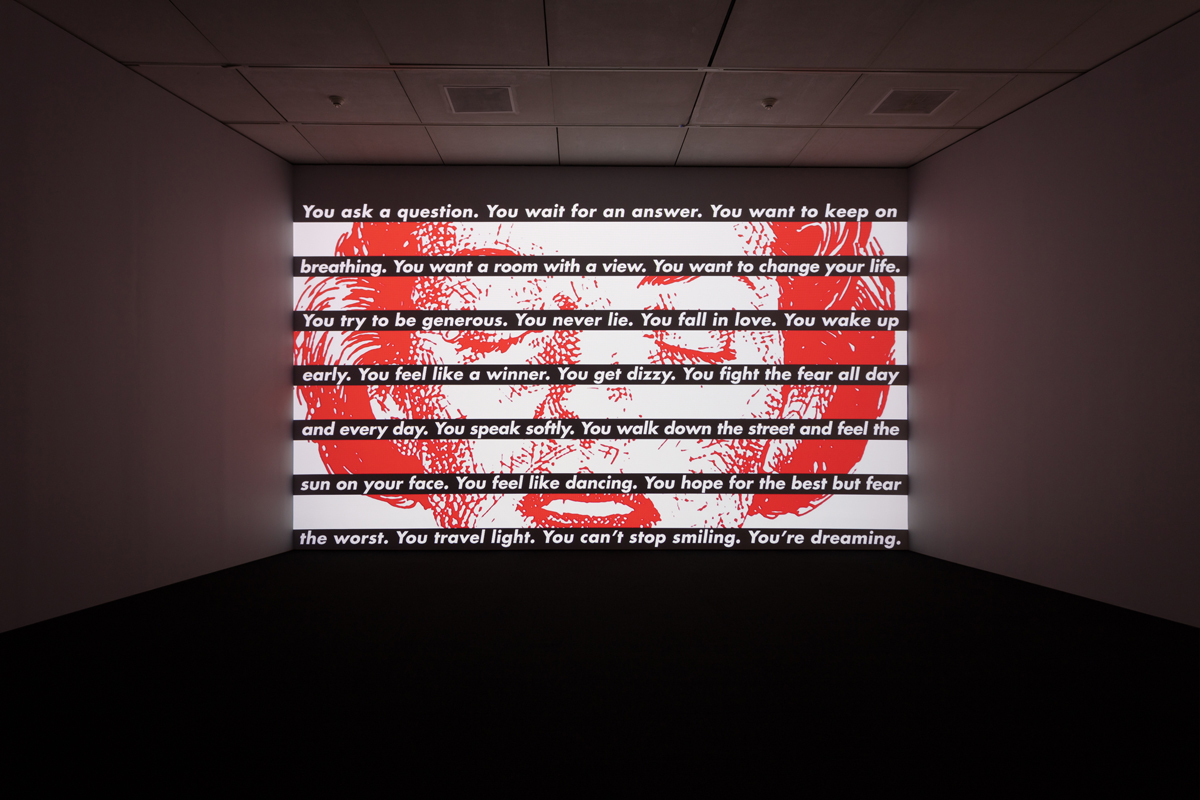

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., installation view. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago. Pictured: Barbara Kruger, Untitled (That’s the way we do it), 2011/2020.

Such interrogations begin in the exhibition’s first gallery, in which an installation raises the question of where the power of artistic influence and a loss of critical efficacy meet. (Or, more simply, of how the implications of Kruger’s words have subtly changed since their first articulation.) The artist’s iconic Untitled (I shop therefore I am) (1987/2019) is presented at the head of the room’s entryway, surrounded by the busy collages of Untitled (That’s the way we do it) (2011/2020) on neighboring walls that similarly deploy her forceful graphic approach, characterized by letters in sans-serif bold typeface on a red ground set upon an emblem-like photographic image. But paying even passive attention to these compositions prompts uncanny doubts as to their origins: some designs are emphatically Kruger-esque, while their slogans are off-key; others possess the artist’s compressed, adage-like intensity, but lack visual acumen. (Still others seem commissioned for, or licensed by, the artist.) Viewers are apt to sift through memories real and imagined as they try to distinguish which, if any, of the images were first made by the artist herself and which were made by others adopting (consciously and not) her style. In fact, Kruger composed these pieces after searching her name online, gathering and arranging pictures from the internet that effectively lock audiences in a prism of appropriation. Whatever Kruger took from mass culture to generate her art has now returned to its source, and her re-appropriations only underscore the increasing porousness of such exchanges. Creating a literal context for I shop . . ., That’s the way we do it points exactly to this cycle of production and consumption as it operates in the realm of self-fashioning.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., installation view. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago. Pictured: Barbara Kruger, Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1987/2019.

Throughout the exhibition one encounters any number of such disarming temporal back-and-forths. Like many other works in the overview, Kruger’s I shop . . . retains its original layout, but it’s made using a more recent technology. While the first iteration was a screen print on vinyl, the current one comprises a large-scale LED screen allowing for the picture to be animated: the looped composition breaks apart into a pile of puzzle pieces that reassemble only to collapse again. By virtue of such medium-based updates, the exhibition necessarily tracks a shift in design tools from Kruger’s cut-and-paste beginnings as a graphic designer at Condé Nast during the late 1960s to the drag-and-drop applications and slow fades of our own time. (Amplifying this sense of many paradigms coexisting here, and of even the distant past lingering in the present, one quiet hallway runs like a spine through the Institute’s galleries, hosting Kruger’s early pasteups, with their diminutive scale, which point even further back to roots in Constructivism and Suprematism.) As important, however, Kruger’s recasting implies a change of effects as the radical disjunctions of modern signage and advertising have given way to the more immersive, softer sell of social media. If the former shattered subjectivity in order to grab attention and make a pitch, the latter doesn’t so much shatter as reconceive and reshape—sustaining attention by rendering subjectivity itself the stuff up for sale.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., installation view. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Kruger calls these updated works “replays,” a term whose condensed wit suggests not only a return to earlier pieces, but also some gaming of the prefix’s different valences in a cultural setting where appropriation is less a critical technique than ubiquitous mode. The staggering visual punch of Kruger’s originals remains intact. (And, truly, if Kruger’s earlier work may have, to many eyes, leaned hard on agitprop, shouting the quiet part out loud in uppercase, their decibel level feels absolutely ratified and necessary—and idiomatic—today.) But just as remarkable is how the hypnotizing techniques of the replays prompt viewers to spend more time with these works. The Reagan-era wording of I shop . . ., as well as that of Untitled (Our Leader) (1987/2020) and Untitled (Your body is a battleground) (1989/2019) literally dissolves into new phrases—from OUR LEADER to OUR LONER, LENDER, LAWYER, and LIAR, for example—providing a kind of visual lure for prolonged contemplation. The approach mirrors and pirates the narcissistic swindle of contemporary social media, where the consumer lives under a happy illusion of being the producer.

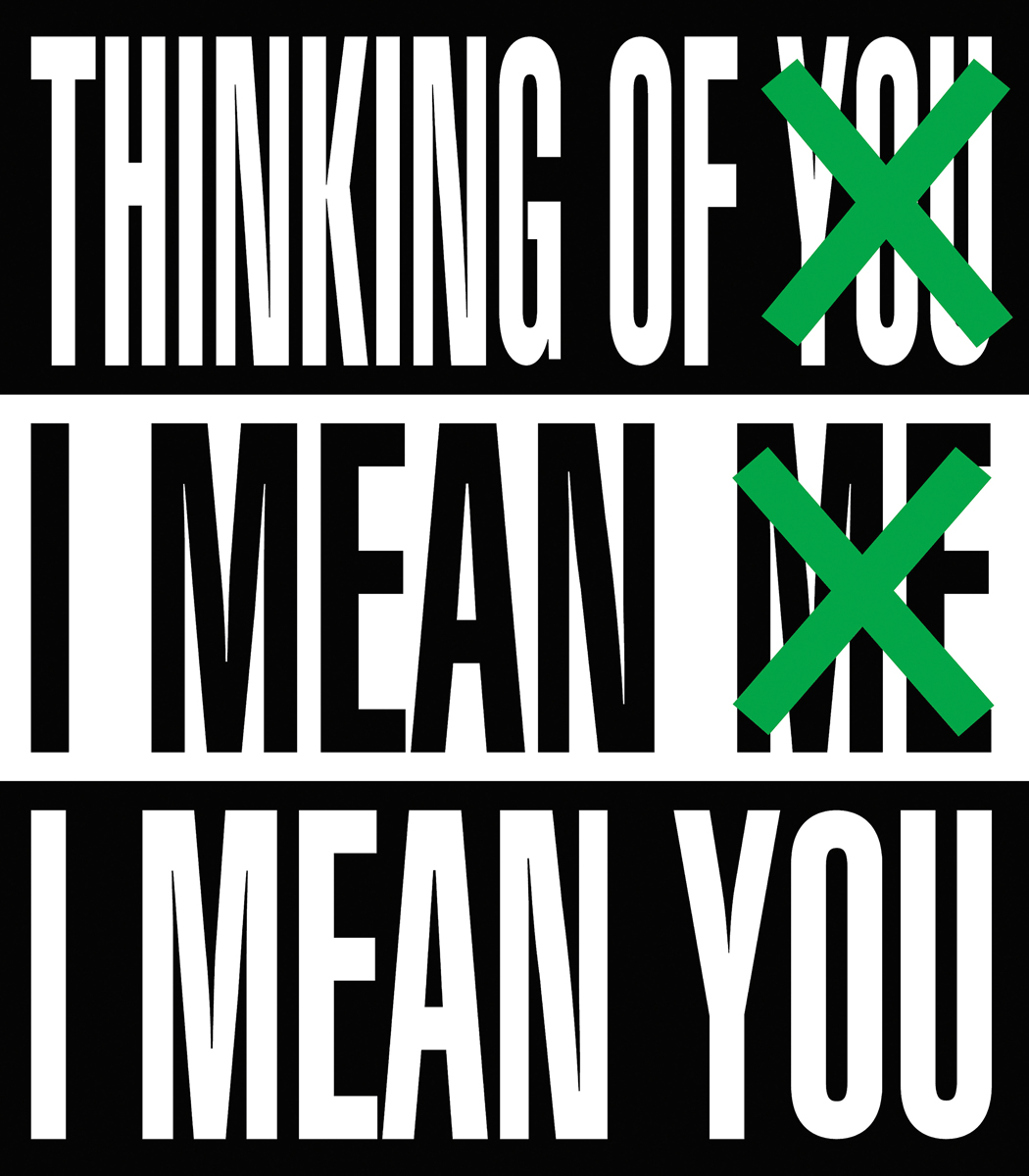

Barbara Kruger, Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., 2019. Digital image. Courtesy of the artist.

When it comes to navigating mass media’s shifting terrain, Kruger is arguably our most important and incisive living artist. This is only confirmed by an immersive installation, Untitled (Selfie) (2020), for which audience members are invited to take photographs of themselves against the backdrop of a wall text that captures the fraught scopophilia of contemporary media culture (“I hate myself and you love me for it / I love myself and you hate me for it”). But to do so, the spectator must first consent to having that image displayed in a live video feed elsewhere in the museum. The very production of the viewer’s own relationship to the image—an act we see in galleries everywhere, embraced here as opposed to prohibited by Kruger, who acknowledges how encountering art now frequently happens only through a lens—becomes a part of the artist’s installation. It is deeply stirring to encounter an exhibition that directly anticipates, instead of indulging or repressing, contemporary viewers’ behaviors.

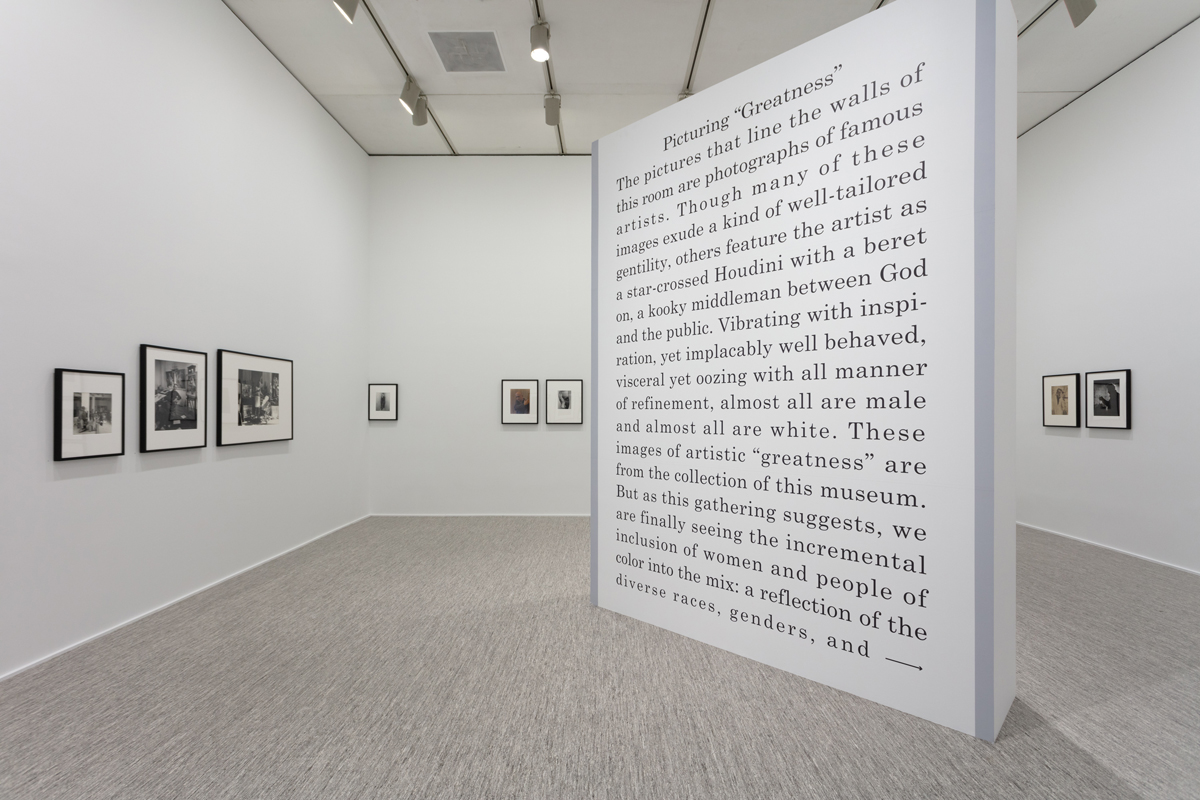

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., installation view. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago. Pictured: Barbara Kruger, Picturing “Greatness,” 1987/2020.

And, moreover, it’s inspiring to witness an artist’s radical perspective (and practice) celebrated not by summation, but rather by extension; and by questions posed, instead of statements made. Few others would, or could, ask audiences approaching the penultimate gallery of their career survey to behold the likes of Picturing “Greatness” (1987/2020). In the work, Kruger assembles portraits of artists from the Institute’s collection and underlines in the running text of a tall placard how most depict white men—before noting how artists (even as institutions are aiming to diversify representations across gender, race, and class) should not be considered immune to the seductions of power. As she further points out, artists may embrace cliché all too readily when given the chance to be recognized within any grand narrative of art. It is imperative, she says, to acknowledge that such success is built on an underlying system—one consisting of “a slice of visual pleasure, a pinch of connoisseurship, a mention of myth, and a dollop of money.” Only in that recognition might the field itself be changed. Ever an artist with a cool eye whose vision is served ice-cold, Kruger to this day stands utterly apart.

Tim Griffin is a writer and curator moving to Los Angeles. His most recent texts for 4Columns have discussed the work of artists Jennie C. Jones and Susan Goldman.